### The Ghost in the Berghof

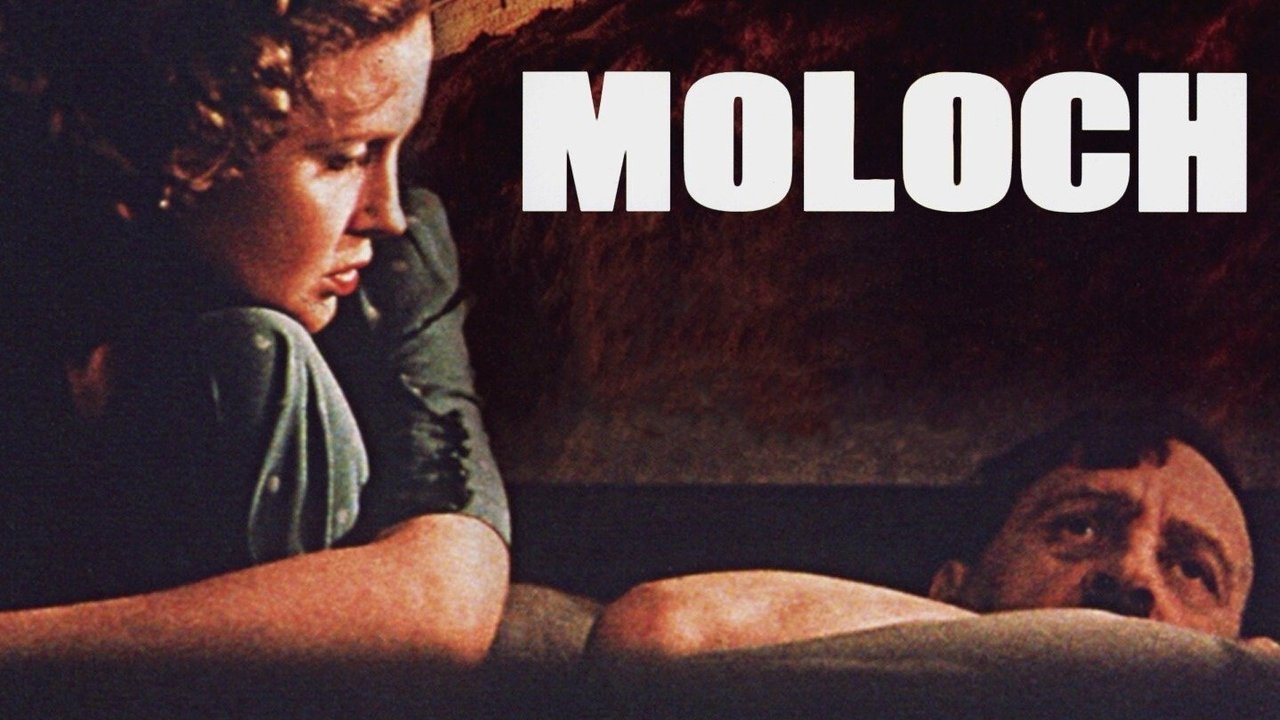

There are films that entertain, films that thrill, and then there are films that crawl under your skin and linger, leaving you in a state of profound unease. Alexander Sokurov's Moloch (1999) belongs firmly in that last category. I recall stumbling upon this one in the 'World Cinema' section of the local rental store, its stark cover art hinting at something far removed from the usual blockbuster fare lining the shelves. It wasn't a casual Friday night pick; it felt like an artifact unearthed, promising a different kind of cinematic experience. And different it certainly was. Moloch doesn't offer the historical sweep or dramatic confrontations one might expect from a film set within Hitler's inner circle during WWII. Instead, it plunges us into a suffocating, dreamlike 24 hours at the Berghof, Hitler's Alpine retreat, focusing relentlessly on the mundane, the petty, and the disturbingly human aspects of monstrous figures.

A Portrait in Decay

The film opens not with marching armies or political intrigue, but with Eva Braun (Yelena Rufanova) dancing alone, lost in a world seemingly detached from the horrors unfolding beyond the mountain peaks. This sets the tone immediately: we are observers in a hermetically sealed environment, a bubble of privilege and paranoia where history feels both omnipresent and strangely irrelevant to the daily rituals. Sokurov, known for his painterly eye and challenging narratives (audiences might later recognize his style in the single-take marvel Russian Ark (2002)), crafts an atmosphere thick with mist – both literal and metaphorical. The Bavarian Alps outside are shrouded, the interiors dimly lit, creating a claustrophobic sense that mirrors the characters' own psychological entrapment.

The narrative, penned by Yuri Arabov (who deservedly won Best Screenplay at Cannes for this), drifts rather than drives. We witness conversations about digestion, vegetarianism, perceived slights, and bouts of hypochondria. Adolf Hitler, portrayed by Leonid Mozgovoy, is not the ranting dictator of newsreels, but a frail, often pathetic figure, prone to infantile outbursts and anxieties about his health. He is Adi to Eva, the "Führer" only in fleeting moments of chilling assertion. It’s a depiction that forces uncomfortable questions: does seeing the tyrant gripe about his bowels diminish his evil, or make the reality of his power even more grotesque?

The Banality Beneath the Banners

What makes Moloch so unsettling is this very focus on the banal. We see Hitler interacting with Eva, Goebbels (Leonid Sokol), and Bormann (part of a visiting entourage) not as architects of genocide, but as individuals caught in bizarrely domestic routines. Eva fusses over Adi, practices gymnastics, and indulges in naive fantasies. Goebbels engages in awkward attempts at humor and philosophical musings. The conversations are often circular, bordering on the absurd. It's Hannah Arendt's "banality of evil" rendered not as bureaucratic indifference, but as personal pettiness and spiritual emptiness occupying the heart of immense power.

The performances are central to this effect. Leonid Mozgovoy is remarkable, embodying Hitler with a physical vulnerability that is deeply unnerving. His movements are often stiff, his pronouncements laced with paranoia and self-pity. He captures a man seemingly collapsing under the weight of his own myth, yet still capable of casual cruelty. Yelena Rufanova as Eva is equally compelling, portraying a woman utterly devoted yet curiously detached, clinging to a warped domesticity amidst impending doom. Her moments of childlike glee juxtaposed with the grim reality outside the Berghof's windows are haunting. There's a strange intimacy forged between them, devoid of genuine warmth but built on mutual dependence and delusion.

An Arthouse Oddity on the Shelf

Finding Moloch on VHS felt like discovering a secret history, a challenging counter-narrative nestled between action flicks and comedies. It wasn’t a tape you’d pop in for escapism. This film demands patience; its pace is deliberate, its visual style often hazy and desaturated, reflecting the moral fog enveloping the characters. Sokurov famously continued exploring figures of immense power and their corrosive effects in his "Tetralogy of Power," which also includes Taurus (Lenin), The Sun (Hirohito), and Faust. Moloch was the first, setting the stage with its audacious premise: to scrutinize absolute power not through its grand gestures, but through its quiet, decaying core.

It’s the kind of film that likely divided renters sharply back in the day. Some might have ejected the tape after twenty minutes, frustrated by the lack of conventional drama. Others, like myself, would have been mesmerized by its sheer audacity, its willingness to stare into the void and find not grand evil, but a disquieting emptiness. There are no easy answers here, no historical lessons spelled out. Instead, Sokurov leaves us contemplating the strange, uncomfortable truth that monsters are often wrapped in the most mundane human frailties. What does it mean when absolute evil complains of a headache?

***

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Moloch is a masterful piece of atmospheric filmmaking and a deeply unsettling character study. Sokurov's direction is assured, creating a unique, dreamlike world, and the central performances from Mozgovoy and Rufanova are brave and unforgettable in their specific, challenging portrayals. Its slow pace and oblique narrative won't appeal to everyone, making it a demanding watch rather than casual entertainment. However, for its artistic ambition, its courage in confronting its subject matter from such an unexpected angle, and the haunting questions it leaves lingering long after the credits roll, it earns a high score. It's a prime example of the challenging, rewarding cinema one could discover tucked away in the video store era.

Final Thought: Decades later, the chilling intimacy of Moloch remains potent – a stark reminder that the most profound horrors can reside not in grand spectacle, but in the quiet, unsettling banality found behind closed doors.