The heavy silver door, etched with warnings older than memory, slides open not on cobwebbed crypts, but on stainless steel and laser grids. It’s an image that perfectly captures Dracula 2000 – an ancient terror repackaged for the turn of the millennium, sealed in a vault pulsing with a dread both timeless and curiously modern. Released right on the cusp of the new century, this wasn't your grandfather's Lugosi, nor the romantic torment of Oldman. This was Dracula plugged into the anxieties and aesthetics of Y2K, a creature feature slicked down with nu-metal aggression and a surprisingly bold, if divisive, reimagining of the vampire’s origins.

### High-Tech Heist, Ancient Horror

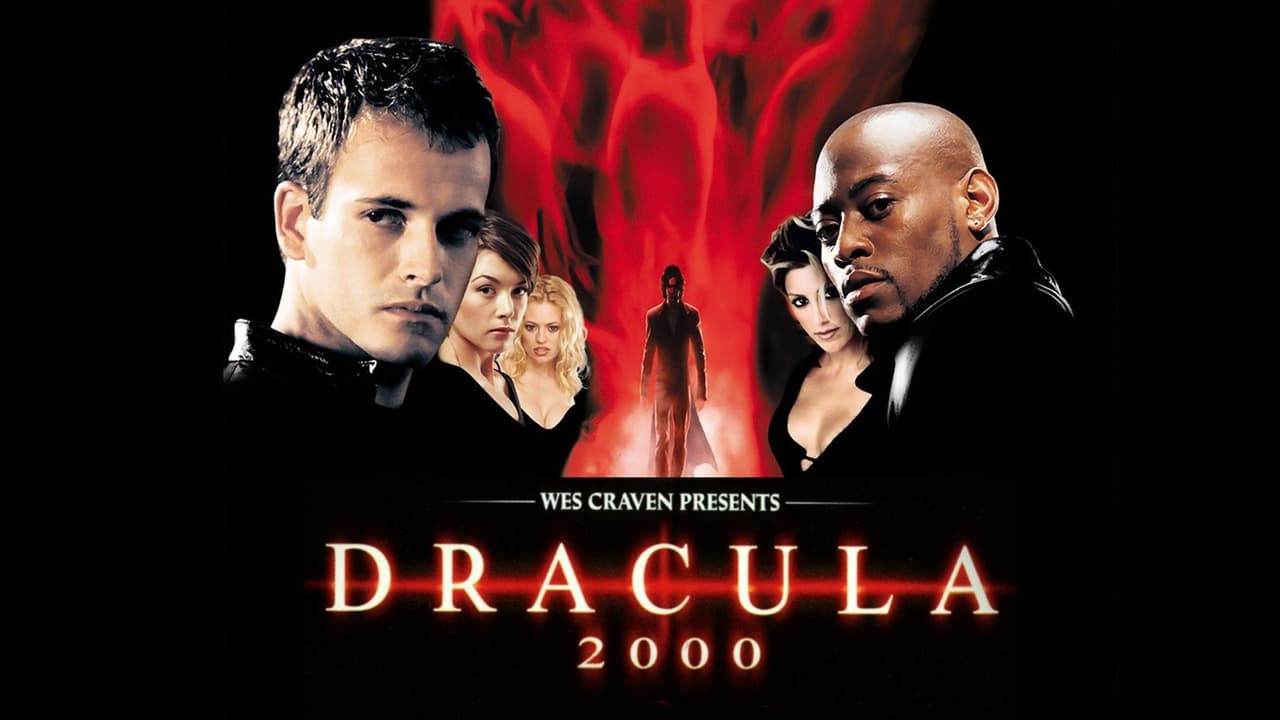

The premise, orchestrated by director Patrick Lussier (a frequent editor for horror maestro Wes Craven, whose Dimension Films backed this venture) and co-writer Joel Soisson, feels ripped from a late-90s thriller. A gang of sophisticated thieves, led by the cocky Marcus (Omar Epps) and the seductive Solina (Jennifer Esposito), targets the high-security vault beneath the antique dealership of Matthew Van Helsing (Christopher Plummer). They expect riches, maybe priceless art. What they find is a sealed silver coffin, impossibly heavy, radiating a cold that chills the soul. Naturally, they steal it, unleashing the slumbering evil within onto an unsuspecting world – specifically, New Orleans during the chaos of Mardi Gras. It’s a setup that promises a collision of worlds: the gothic menace of Dracula against the neon-drenched, bead-throwing frenzy of the Big Easy.

### The Smolder of the New Blood

At the heart of the darkness stands Gerard Butler, then a relative unknown, stepping into the iconic cape. Forget ethereal aristocrats; Butler’s Dracula is pure predatory charisma. He's lean, intense, with eyes that burn through the screen – an almost rockstar interpretation of the Count. Reportedly enduring painful contact lenses and cumbersome fangs, Butler fully commits, bringing a raw physicality to the role that feels distinct. He’s less a creature of subtle suggestion and more a force of nature, commanding attention in every scene. Opposite him, the legendary Christopher Plummer lends undeniable gravitas as Van Helsing, revealed here not as the original Abraham, but as a man cursed with longevity, forever bound to guarding the monster he failed to destroy centuries ago. Jonny Lee Miller, fresh off Trainspotting (1996), plays Simon Sheppard, Van Helsing’s protégé, who must track Dracula down alongside Van Helsing’s estranged daughter, Mary (Justine Waddell).

### Mardi Gras Mayhem

Patrick Lussier, leveraging his editor's eye, crafts a visually slick film. The move to New Orleans during Mardi Gras proves inspired, offering a backdrop of pulsing crowds, vibrant chaos, and easy anonymity for a creature of the night. Some of the film's most memorable sequences unfold amidst the revelry – a chase through crowded streets, a terrifying confrontation in a packed Virgin Megastore (remember those?). Lussier uses the setting effectively to heighten the sense of vulnerability; where do you hide when the monster can blend seamlessly into the masked chaos? The pounding soundtrack, featuring Y2K-era heavy hitters like Disturbed, Pantera, and System of a Down, further anchors the film in its specific moment, adding a layer of aggressive energy that feels both dated and oddly perfect for this interpretation. Filming during the actual Mardi Gras reportedly presented unique challenges, adding an authentic layer of controlled chaos to the production.

### Spoiler Alert! That Controversial Crucifixion

Where Dracula 2000 truly attempts to leave its mark – and arguably stumbles for many – is its audacious reveal of Dracula’s true identity. Forget Wallachian warlords. This film posits that Dracula is none other than Judas Iscariot, cursed to walk the night as a vampire for his betrayal of Christ. The silver, the crucifixes, the aversion to holy ground – it all clicks into place within this new mythology. It’s a swing for the fences, aiming for theological horror, and its effectiveness remains debated. Did that twist genuinely shock you back then? For some, it felt like a bold, blasphemous stroke of genius; for others, a clumsy retcon that strained credulity. It certainly gives the final act, involving a confrontation heavy with crucifixion imagery, a unique, if potentially uncomfortable, flavor. This deviation from Bram Stoker was a significant gamble, contributing to the film's polarizing reception.

### A Millennium Vampire's Legacy

Despite its visual flair, Butler's magnetic performance, and its ambitious reimagining, Dracula 2000 didn't quite reignite the franchise as Dimension Films likely hoped. Made for a hefty $54 million (around $95 million today), it grossed only $47 million worldwide (about $83 million today), marking it a commercial disappointment. Critics were largely unkind, pointing to plot holes and sometimes uneven performances beyond the leads. Yet, watching it now, there's an undeniable nostalgic charm. It captures a specific moment in horror – that post-Scream, pre-9/11 era where studios were trying to make horror "cool" and "modern" again, often with mixed results. The blend of gothic tropes with late-90s tech, fashion, and music feels like a time capsule. The practical effects hold up reasonably well, particularly the unsettling transformations, offering that tactile grisliness we crave from the era. It even spawned two direct-to-video sequels, Dracula II: Ascension (2003) and Dracula III: Legacy (2005), continuing the Judas storyline, though without the original cast or budget.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: Dracula 2000 gets points for sheer audacity, Gerard Butler's star-making intensity, Christopher Plummer's gravitas, and its stylish, atmospheric direction that effectively uses its New Orleans setting. It’s a genuinely interesting take on the legend, anchored firmly in its Y2K aesthetic. However, it's hampered by a sometimes clunky script, underdeveloped supporting characters, and a central twist that remains highly divisive. It doesn't fully capitalize on its potential, feeling slick but occasionally hollow.

Final Thought: While far from a masterpiece, Dracula 2000 is a fascinating artifact of turn-of-the-millennium horror filmmaking. It’s a guilty pleasure for some, a curious misfire for others, but undeniably memorable for its bold choices and for giving us Butler's brooding, rockstar take on the Prince of Darkness – a specific flavor of vampire we haven't quite seen since. It’s the kind of film you’d grab off the “New Releases” shelf at Blockbuster, intrigued by the cover, and get exactly the kind of glossy, slightly edgy, late-night creature feature promised.