Alright, settle in and dim the lights. Tonight, we're digging out a tape that might feel just a hair past our usual 90s hunting ground, but trust me, its soul belongs right here in the era of seeking out something different on the video store shelves. I'm talking about Lone Scherfig's Dogme 95 entry, Italian for Beginners (original title: Italiensk for begyndere) from 2000. Remember the Dogme movement? That Danish filmmaking collective that threw out the rulebook – no artificial lighting, handheld cameras only, shot on location? It was a fascinating, sometimes jarring, reaction against the gloss of the late 90s, and this film... well, this film was the warm, beating heart that proved the experiment could yield something truly lovely.

Finding Warmth in the Danish Winter

The premise itself is deceptively simple. In a drab, perpetually overcast Danish suburb, a handful of lonely souls find their lives intersecting, primarily through a local community college Italian course. We meet Andreas (Anders W. Berthelsen), a sensitive young pastor temporarily assigned to the town's church after his predecessor's departure (and his own personal crisis); Olympia (Anette Støvelbæk), clumsy and kind, burdened by a belligerent, invalid father; Karen (Ann Eleonora Jørgensen), a hairdresser whose alcoholic mother casts a long shadow; Halvfinn (Lars Kaalund), the perpetually furious hotel manager with a hidden grief; Jørgen (Peter Gantzler), a painfully shy hotel porter nursing a secret crush; and Giulia (Sara Indrio Jensen), an Italian waitress newly arrived in town. Their individual stories are marked by loss, awkwardness, and quiet desperation, yet the film never wallows. Instead, it observes them with profound empathy.

The Dogme Touch: Less is More

Now, about that Dogme 95 connection. Italian for Beginners was officially Dogme #12. Watching it today, the aesthetic is undeniable: the slightly jerky handheld camerawork, the reliance on natural light that sometimes leaves faces in shadow, the soundscape capturing the ambient hum of reality rather than a polished score (though there is some non-diegetic music, technically bending the rules slightly – a point often noted by Dogme purists!). But what Scherfig, who also wrote the screenplay, achieved was remarkable. She used these limitations not as gimmicks, but as tools to foster an almost startling intimacy. We're right there with these characters, sharing their hesitant glances, their fumbled conversations, their moments of unexpected connection. It strips away artifice, forcing us to focus entirely on the human element. It’s worth noting this was the first Dogme film directed by a woman, and it became, somewhat ironically given the movement's anti-commercial stance, one of its biggest international successes, grossing over $16 million worldwide against a budget reportedly under $1 million. It proved that raw filmmaking could also be deeply affecting and widely appealing.

Performances That Breathe Authenticity

The ensemble cast is uniformly superb. There isn't a false note among them. Anders W. Berthelsen brings a gentle uncertainty to Andreas, a man trying to find faith in others when his own is shaken. Anette Støvelbæk as Olympia is heartbreakingly vulnerable yet possesses an inner resilience that slowly surfaces. Ann Eleonora Jørgensen's Karen navigates grief and the possibility of new love with a quiet dignity that feels utterly real. And Peter Gantzler as Jørgen? His portrayal of profound shyness is a masterclass in understated acting; you root for him with every fiber of your being. Even Lars Kaalund's Halvfinn, initially presented as almost comically angry, reveals layers of pain that explain, if not excuse, his abrasive nature. The Dogme style puts immense pressure on actors – there are no fancy camera moves or dramatic lighting cues to hide behind. Their performances are the film, and they rise to the challenge beautifully, creating characters who feel less like fictional constructs and more like people you might actually know.

More Than Just Language Lessons

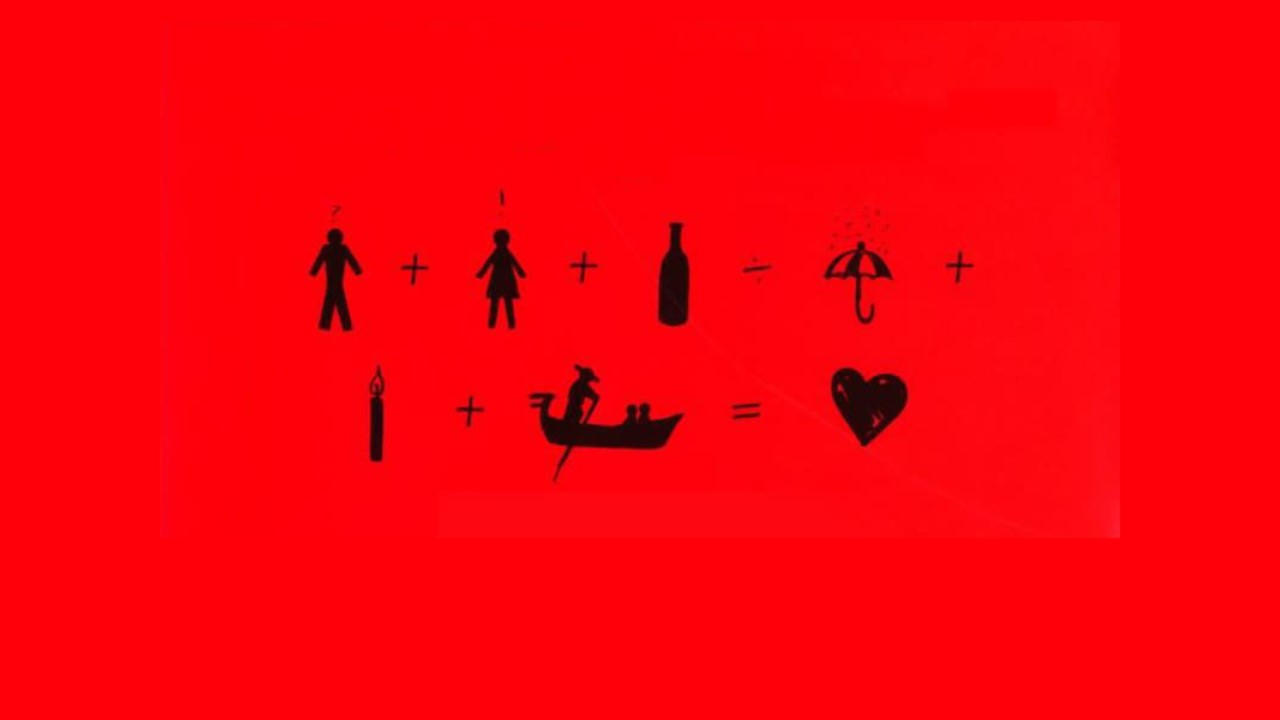

The Italian class itself serves as more than just a plot device. It becomes a fragile sanctuary, a neutral ground where these damaged individuals can tentatively lower their guards. Learning this new language, often associated with passion and romance, becomes a quiet act of hope, a fumbling attempt to communicate not just in Italian, but on a deeper emotional level. There's a gentle, observational humor here too, born not from contrived jokes but from the inherent awkwardness of human interaction, the misunderstandings, the small social anxieties we all recognize. Does the shared trip to Venice near the end feel a little convenient? Perhaps. But by that point, the film has earned its moment of warmth and resolution. You want these people to find a measure of happiness.

A Latecomer with a 90s Indie Soul

While technically released in 2000, Italian for Beginners feels intrinsically linked to the independent film spirit that blossomed in the 90s. It's the kind of movie you might have discovered tucked away in the "Foreign Films" section of Blockbuster or your local indie video store, a quiet counterpoint to the louder fare dominating the New Releases wall. I remember seeking out Dogme films back then, intrigued by the manifesto, sometimes challenged by the rawness, but always fascinated. This one stood out for its accessibility and its sheer, unadulterated warmth. It bypassed intellectual coolness for genuine emotional connection.

Rating: 8/10

Italian for Beginners is a testament to the power of character-driven storytelling and proof that technical limitations can inspire profound creativity. Its Dogme roots give it a raw immediacy, but its enduring appeal lies in its deep empathy, outstanding performances, and the gentle, hopeful message that connection can blossom in the unlikeliest of circumstances. The handheld camerawork might not be for everyone, and the pacing is deliberately unhurried, but the emotional payoff is rich and deeply satisfying.

It remains a small miracle of a film – a reminder that sometimes, the most moving stories are the quietest ones, found not in grand gestures, but in the shared vulnerability of simply trying to speak the same language.