It’s a question that lingers long after the credits roll: How does one truly capture the essence of a bygone era, particularly one steeped in myth and verse like the age of Arthurian legend? Most filmmakers opt for sweeping vistas, muddy battles, and a dose of gritty realism. But Éric Rohmer, a director synonymous with the nuanced moral landscapes of contemporary French life (My Night at Maud's, Claire's Knee), took a dramatically different path with his 1978 curiosity, Perceval le Gallois. Discovering this on a dusty VHS shelf, perhaps tucked away in the foreign film section of a discerning video store, felt less like renting a movie and more like unearthing a strange, illuminated manuscript brought to flickering life.

### A Canvas, Not a Castle

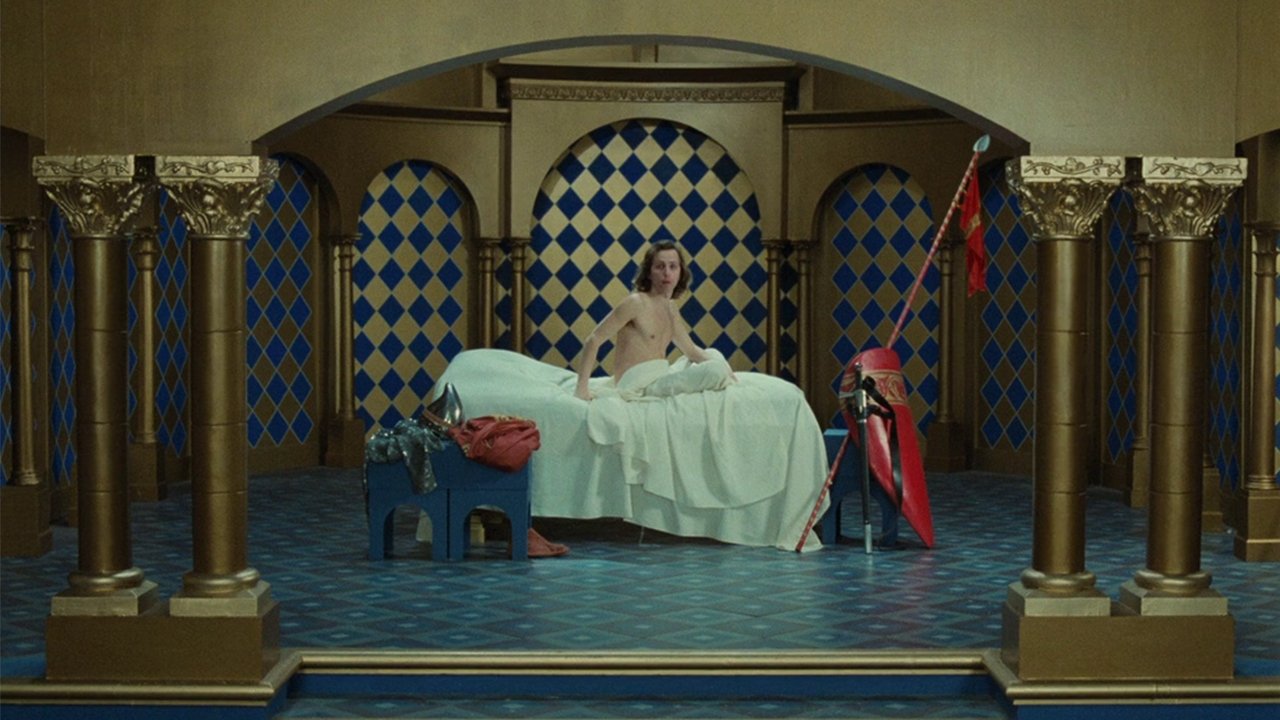

Forget any expectation of historical verisimilitude. Rohmer doesn't recreate the 12th century; he interprets it through the lens of its own art. The first thing that strikes you about Perceval is its astonishing, deliberate artificiality. The sets are minimalist, theatrical constructions – stylized trees painted gold, schematic castles that resemble illustrations from a medieval text, flat perspectives that defy cinematic depth. It’s filmed entirely on a soundstage, creating a hermetically sealed world. This isn't a flaw; it's the film's foundational principle. Rohmer aimed to evoke the spirit and visual language of the period's art and literature, particularly Chrétien de Troyes' unfinished verse romance, rather than mimic reality. The effect is initially jarring, demanding a significant adjustment from the viewer. Does it feel stilted? Perhaps. But it also creates a unique dreamlike space where the story's archetypal nature can resonate without the distractions of conventional filmmaking.

### Words Made Flesh, Verse Made Song

Rohmer's fidelity extends beyond the visuals to the very language of the film. He adapted Chrétien de Troyes' text with meticulous care, retaining its poetic structure and archaic flavour. The dialogue isn't just spoken; it's often delivered in a measured, almost chanted rhythm. More strikingly, passages of narration and internal thought are frequently sung, sometimes by the characters themselves, sometimes by an on-screen chorus of musicians and singers who observe and comment on the action like figures in a medieval tapestry. This integration of music and spoken word further distances the film from naturalism, reinforcing its connection to older forms of storytelling – the ballad, the chanted epic. It requires patience, an attuning of the ear to its peculiar cadence, but it underlines the film’s commitment to its source material in a way few adaptations ever attempt.

### The Innocent Abroad in Camelot

At the heart of the tale is Fabrice Luchini in an early, captivating role as Perceval. Luchini, who would become a stalwart of French cinema, embodies the young knight's profound naiveté with wide-eyed sincerity. Raised in ignorance of chivalry, his journey is one of awkward learning, social blunders, and spiritual awakening. His performance perfectly suits Rohmer's stylized approach – it's less about psychological depth in the modern sense and more about embodying an archetype, a figure moving through a symbolic landscape. Supporting players, including André Dussollier as Gawain, similarly adopt this presentational style. It's acting as recitation, as embodiment of text, which can feel alienating if you're seeking gritty realism, but feels entirely cohesive within the film's self-contained universe. What does Perceval's journey, his crucial failure to ask the right question at the Grail Castle, reveal about the gap between intention and action, between innocence and wisdom? The film doesn't offer easy answers, instead letting the ambiguity of the original poem hang in the air.

### A Rohmer Anomaly?

For those familiar only with Rohmer's later, more naturalistic work, Perceval stands as a fascinating, almost baffling outlier. Yet, the intellectual rigor, the deep engagement with text, and the exploration of moral and spiritual development are hallmarks of his entire career. It’s said Rohmer spent years researching and planning the film, driven by a personal fascination with the medieval period. Its initial reception was, perhaps predictably, mixed. Critics accustomed to historical epics or Rohmer's contemporary tales didn't always know what to make of its stark, theatrical presentation. Yet, watching it now, possibly on a format far removed from its original cinematic context, its sheer audacity is impressive. It’s a film utterly committed to its unique vision, demanding engagement on its own terms.

### Finding the Grail in the Video Store

Perceval le Gallois wasn't likely a weekend blockbuster rental alongside Raiders of the Lost Ark or The Terminator. It represents a different kind of VHS-era discovery – the unexpected art film, the challenging watch that rewards patience. It’s the kind of tape you might have rented on a whim, intrigued by the cover or the director's name, and found yourself transported to a place unlike anything else on screen. It doesn't offer easy comforts, but its singular artistry and intellectual depth provide a different kind of satisfaction. It's a reminder that cinema, even in the home video era, could be a portal to the genuinely strange and thought-provoking.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: This score reflects the film's undeniable artistic achievement, its bold stylistic choices, and its faithful, intelligent adaptation of the source material. Éric Rohmer's unique vision is fully realized. However, its deliberate artificiality, stylized performances, and challenging pace make it far from accessible entertainment. It earns high marks for ambition and execution within its specific goals, but its demanding nature prevents a higher, more universally recommendable score for a general audience seeking conventional narrative pleasure.

Final Thought: Perceval le Gallois remains a cinematic enigma – a medieval poem reimagined as minimalist theatre, a testament to a director's uncompromising vision that continues to puzzle and provoke decades later. What other film dares to be quite so... itself?