### The Sound That Cracks the Sky

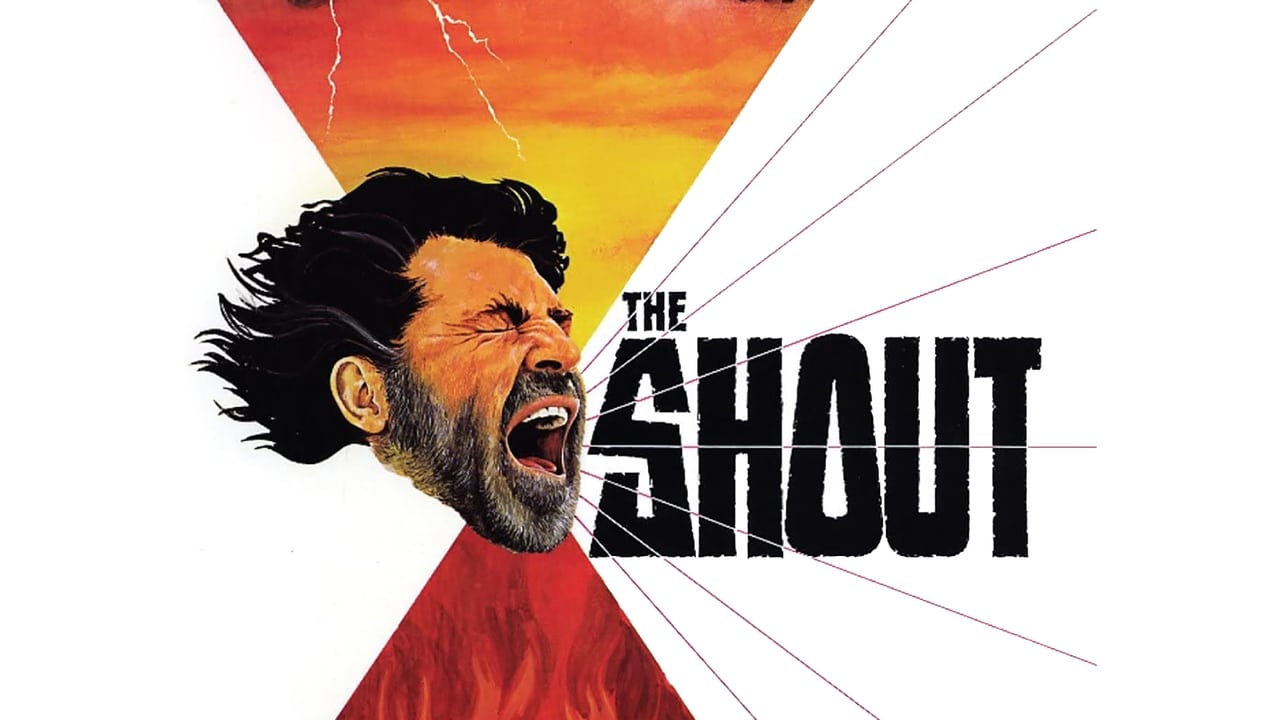

Some films don't just tell a story; they seep under your skin, leaving a residue of unease that lingers long after the VCR clicks off. Jerzy Skolimowski's The Shout (1978) is precisely that kind of experience. It wasn’t one you’d typically find nestled between the big action flicks or goofy comedies at the video store; this was often relegated to the 'arthouse' or 'horror' shelf, a tape whose stark cover art hinted at something profoundly strange within. Watching it again now, it’s clear this wasn't just youthful perception – The Shout remains a uniquely disturbing piece of British cinema, a psychological puzzle box wrapped in folk horror dread.

The film unfolds through a framing device – a cricket match at a rural asylum, where Robert Graves (played with a gentle curiosity by Tim Curry in an early role) scores the match alongside Anthony Fielding (John Hurt). Fielding begins recounting a story told to him by another patient, Charles Crossley (Alan Bates), a man claiming extraordinary, terrifying abilities learned during eighteen years among Aboriginal Australians. The core narrative then shifts to Crossley imposing himself upon Fielding, a composer experimenting with sound, and his wife Rachel (Susannah York), in their isolated North Devon home.

### An Unwelcome Guest, An Unholy Power

What immediately grips you is Alan Bates' central performance. Crossley isn't a typical movie monster; he’s intelligent, articulate, almost charming, yet radiating a palpable wrongness. Bates plays him with a predatory stillness, his eyes holding a chilling certainty about his claimed powers – particularly the titular "terror shout," learned from an Aboriginal shaman, supposedly capable of killing anyone who hears it unprotected. Is he a conman, a madman, or something genuinely supernatural? The film masterfully refuses to provide easy answers, forcing us, alongside Hurt's increasingly unnerved Fielding, to constantly question what we're witnessing. Bates, who apparently took the role very seriously, embodies this ambiguity perfectly. His claim, delivered with unnerving conviction, feels less like a boast and more like a statement of terrible fact.

John Hurt, ever the master of conveying quiet desperation, serves as our anchor to rationality, yet even he finds his scientific detachment eroding under Crossley's influence. His work with electronic music and sound becomes ironically juxtaposed with Crossley's primal, elemental power. Susannah York delivers a complex portrayal of Rachel, caught between fascination and repulsion, her vulnerability becoming a battleground for the two men. The tension in their remote cottage becomes almost unbearable, amplified by Skolimowski's often unsettling directorial choices.

### Sounds and Silence in Coastal Isolation

Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski, known for his distinctive visual style (later seen in films like Moonlighting (1982) and Deep End (1970)), uses the seemingly idyllic Devon landscape to create a profound sense of isolation and dread. The crashing waves, the wind whistling through the dunes, the crying gulls – the natural soundscape is meticulously crafted, making Crossley's claims about manipulating sound feel almost plausible within this heightened environment. Skolimowski employs long takes, off-kilter framing, and moments of near-surreal imagery (like a seemingly significant detached shoe buckle) that contribute to the film's dreamlike, or rather nightmare-like, quality.

The film was adapted from a short story by Robert Graves (the same Graves who appears briefly as Curry's character), and it retains that literary sense of uncanny intrusion into the mundane. Interestingly, the adaptation process involved both Skolimowski and Michael Austin, and they managed to expand the story while retaining its core unsettling ambiguity. It’s a testament to their work, and Skolimowski's direction, that the film won the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival, tying with Bye Bye Monkey. This wasn't some B-movie schlock; it was recognized for its artistry even then, though its disturbing nature perhaps kept it from wider mainstream appeal. Finding it on VHS felt like unearthing a potent secret.

### The Lingering Echo

What truly makes The Shout stick with you is its exploration of belief, power, and the fragility of perceived reality. Crossley’s power, whether real or imagined, derives its strength from suggestion and the psychological manipulation of his hosts. Does the shout actually kill, or is it the belief in its power that shatters the victim? The film cleverly leaves this open, suggesting that the primal fears Crossley taps into are perhaps more potent than any rational explanation. The snippets of Aboriginal culture are presented not exploitatively, but as a source of ancient, perhaps dangerous, knowledge utterly alien to the polite English setting, adding another layer to its unsettling power dynamics.

The practical sound design required to even suggest the 'terror shout' must have been a fascinating challenge in the late 70s. While we don't fully experience its alleged lethal potential on screen for obvious reasons, the threat of it, the build-up and the reactions it provokes, are remarkably effective. It becomes a symbol of raw, untamed power disrupting the ordered world.

---

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: The Shout is a masterclass in sustained psychological dread and ambiguity. Alan Bates delivers an unforgettable, chilling performance, perfectly complemented by Hurt and York. Skolimowski's direction creates a unique and deeply unsettling atmosphere that leverages its coastal setting brilliantly. While its deliberate pace and refusal of easy answers might not appeal to everyone, its artistic merit and lingering power are undeniable. It loses a point perhaps for the framing device feeling slightly less integrated than the core narrative, but overall, it's a potent and haunting piece of cinema.

Final Thought: Long after the tape rewinds, the silence in the room can feel heavy, charged with the memory of Crossley's impossible claim. It’s a film that doesn't just entertain; it burrows into your mind and asks uncomfortable questions about the sounds we hear, and the ones we fear. A truly distinctive gem from the fringes of 70s horror.