It often begins with a fragment, doesn't it? A stray image, a discordant sound, a feeling that lingers long after the VCR whirred to a stop and the tape ejected. With Nicolas Roeg's Bad Timing (1980), the fragments are the film. Watching it again, decades after first encountering its unsettling power on a rented cassette, is like trying to piece together a shattered mirror – you see reflections of passion, obsession, and profound hurt, but the whole picture remains elusive, deliberately fractured by a master filmmaker.

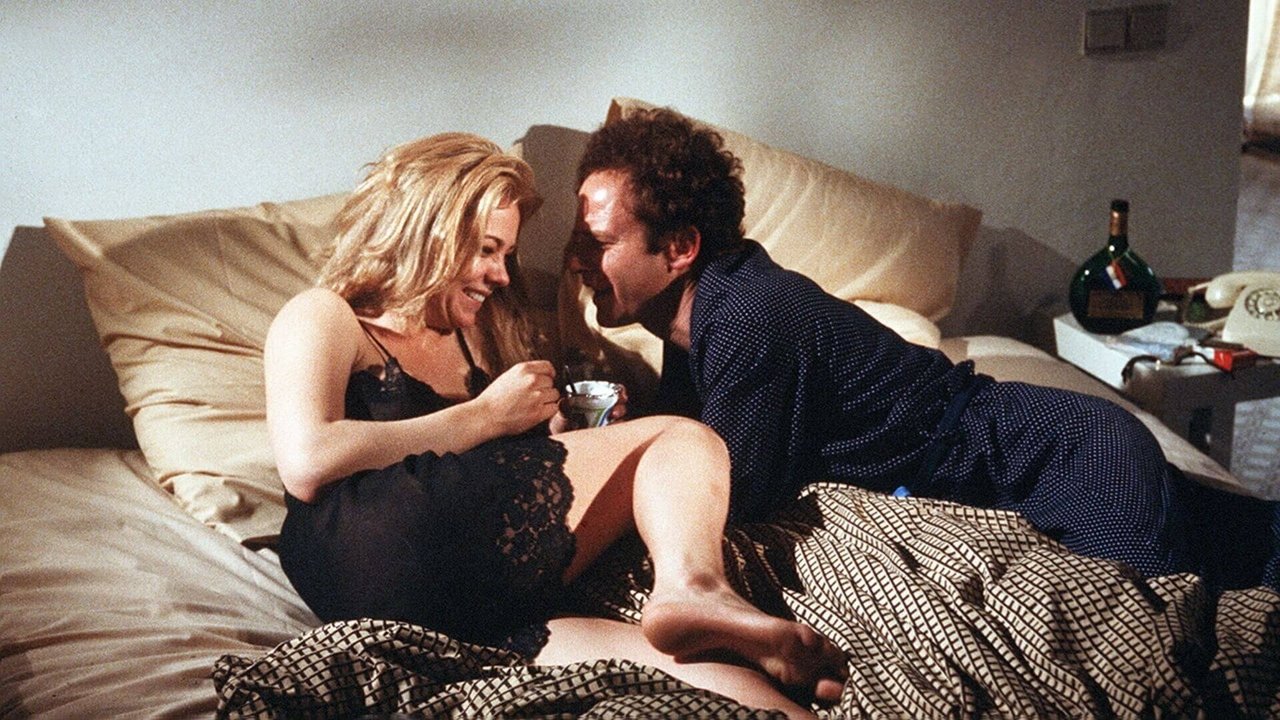

This isn't a comfortable watch; it never was. Tucked away in the 'Drama' section of the video store, maybe sometimes misfiled under 'Thriller', its stark cover art hinted at something more complex than the usual fare. And complex it is. Set against the backdrop of a cold, almost clinically observed late-70s Vienna, the film dissects the autopsy of a devastatingly intense relationship between Milena Flaherty (Theresa Russell in a performance of astonishing, raw vulnerability) and Dr. Alex Linden (Art Garfunkel, surprisingly effective as the analytical psychiatrist consumed by obsessive love).

Fragments of a Love Affair

What immediately sets Bad Timing apart, and what cemented Roeg's reputation (following works like Don't Look Now and The Man Who Fell to Earth) as a cinematic puzzle-maker, is its non-linear structure. We don't experience Alex and Milena's story chronologically. Instead, Roeg, alongside writer Yale Udoff, throws us into the immediate aftermath of Milena's apparent suicide attempt. As Inspector Netusil (Harvey Keitel, bringing his grounded intensity) investigates the circumstances in the hospital, Alex's memories flood the screen – disjointed, obsessive, looping back on themselves.

This fragmented approach isn't just a stylistic flourish; it's fundamental to the film's themes. Memory itself becomes unreliable, coloured by Alex's possessiveness and Milena's volatile emotional state. We see moments of ecstatic connection juxtaposed with bitter arguments, tenderness undercut by manipulation. Is Alex's recollection accurate, or is it a self-serving narrative constructed to absolve himself? The film forces us, like Inspector Netusil, to sift through the emotional debris, questioning every perspective. What truly happened in that Vienna apartment? The ambiguity is the point.

Vienna's Cold Embrace

The choice of Vienna is inspired. It's a city steeped in history, art, and psychoanalysis, but Roeg presents it not as a romantic postcard backdrop, but as a place of surveillance, chilly corridors, and detached observation. The atmosphere mirrors the clinical nature of Alex's profession and the way he dissects Milena, both emotionally and, implicitly, intellectually. There’s a palpable sense of decay beneath the city's imperial facade, echoing the disintegration of the central relationship. I recall finding a copy once that still had the sticker from the long-gone ‘Video Palace’ on the spine; even holding the tape felt like handling something slightly illicit, a glimpse into a world far removed from suburban multiplexes.

Performances That Scar

The film hinges on its central performances. Theresa Russell, who would become Roeg's wife and frequent collaborator, is simply electrifying. She embodies Milena's desperate yearning for connection and freedom, her self-destructive impulses, and her fierce intelligence. It's a brave, unvarnished portrayal that refuses easy categorization. Art Garfunkel, stepping away from his musical persona, delivers a chillingly controlled performance. His Alex is outwardly calm, intellectual, almost passive, but beneath the surface lurks a dangerous possessiveness. The casting feels deliberate; his gentle image makes the character’s darker undercurrents all the more disturbing. And Keitel, as the persistent detective, serves as our anchor, his methodical questioning probing the layers of denial and obsession.

A Controversial Classic

It’s worth remembering just how controversial Bad Timing was upon release. Its original distributor, the Rank Organisation, famously disowned it, with one executive reportedly calling it "a sick film made by sick people for sick people." It’s a statement that speaks volumes about the film's power to provoke and disturb. It refuses to offer easy answers or moral judgments, confronting viewers with the uncomfortable realities of sexual politics, emotional manipulation, and the destructive potential of obsessive love. Finding it on VHS felt like an act of cinematic archaeology, uncovering a film deliberately buried by the establishment. Did Rank’s reaction inadvertently cement its cult status among serious film fans? Perhaps. The production itself wasn't straightforward, navigating the complexities of depicting such raw emotional and psychological terrain. Roeg's background as a gifted cinematographer (Lawrence of Arabia, Fahrenheit 451) is evident in every frame; the visual language is as crucial as the dialogue in conveying the fractured narrative and turbulent emotions.

Lingering Questions

What stays with you after Bad Timing? It’s the unsettling feeling, the ambiguity, the sheer force of Russell's performance. It’s a film that doesn't just show you a relationship falling apart; it makes you feel the disorientation, the pain, the moments of connection warped by possession. It asks profound questions about the nature of love and obsession, about how we remember and reconstruct the past, and about the darkness that can lie beneath a civilized surface. Doesn't the way Alex studies Milena, trying to pin her down like a specimen, reflect anxieties about control and understanding that still resonate today?

Rating: 9/10

Bad Timing earns this high score for its uncompromising artistic vision, Nicolas Roeg's masterful direction, the unforgettable performances by Theresa Russell and Art Garfunkel, and its bold, non-linear exploration of complex and disturbing themes. It's not an easy film, and its fragmented structure and challenging subject matter demand concentration, making it perhaps less immediately accessible than some other cult classics. However, its intellectual depth, emotional power, and stylistic brilliance make it a landmark of 1980s cinema – a 'sick film' only in its unflinching diagnosis of a toxic obsession.

It remains a potent reminder that sometimes the most compelling stories are found not in neat narratives, but in the sharp, unsettling fragments of lives lived intensely, if tragically. A true gem for those seeking challenging, thought-provoking cinema from the VHS era.