### The Stillness Before the Change

There’s a certain quietude that settles over Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Boys from Fengkuei (1983), a stillness that feels less like peace and more like the held breath before an inevitable shift. It’s a film that doesn't shout its intentions; instead, it observes. Watching it now, perhaps discovered on a dusty, lesser-rented tape back in the day, or maybe sought out as a cornerstone of the Taiwanese New Wave, feels like uncovering a different kind of 80s memory – one devoid of synth-pop montages and explosive action, replaced by the patient gaze on lives drifting between adolescence and the daunting prospect of adulthood. It arrived the same year as Return of the Jedi and Scarface, yet feels worlds away, capturing a specific, poignant reality that resonates with surprising clarity decades later.

### From Island Boredom to City Blues

The setup is deceptively simple: A group of restless young men – Ah-Ching (Doze Niu), Kuo-tsu (Chang Shih), and Ah-Jung (Tou Chung-hua) among them – idle away their days in the small fishing archipelago of Fengkuei (Penghu). Their lives are marked by petty scuffles, aimless wandering, gambling, and the simmering frustration of limited horizons. There's an almost documentary-like feel to these early scenes, capturing the languid rhythm of island life and the volatile energy of youth with nowhere to direct itself. When trouble forces them to leave, they trade the familiar sea breeze for the overwhelming clamor of the port city of Kaohsiung, seeking work and perhaps, unknowingly, a future. What they find instead is a different kind of displacement, a deeper sense of being adrift amidst the city's indifferent hustle.

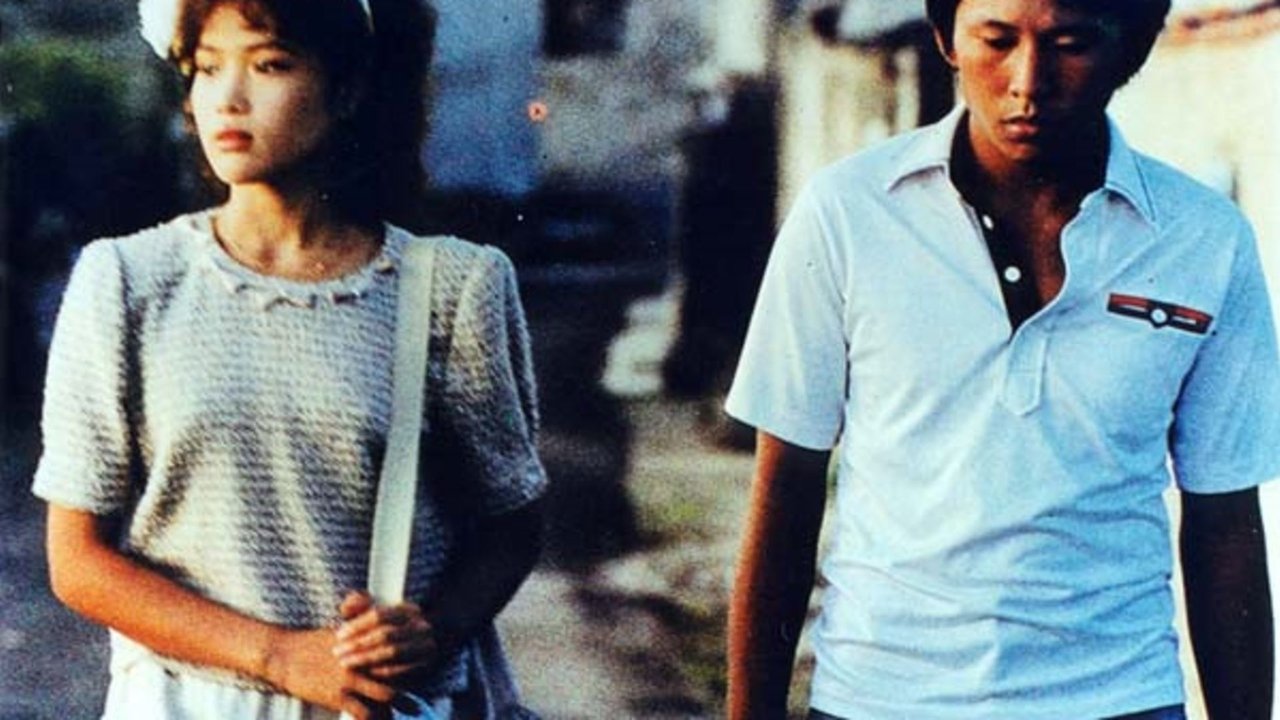

### Authenticity in Aimlessness

What truly anchors the film are the performances. There's a remarkable lack of affectation in the young cast, many of whom were relatively inexperienced. Doze Niu, as the central figure Ah-Ching, carries a quiet sensitivity beneath the bravado, his observations forming the film's emotional core. We see the world largely through his eyes – the allure and eventual disappointment of the city, the tentative steps towards romance, the dawning realization that the bonds of their youth are fraying. Chang Shih and Tou Chung-hua embody different facets of the group dynamic, their interactions feeling utterly naturalistic. They aren’t playing archetypes; they feel like genuine friends, caught in that confusing space where loyalty clashes with the individual need to move forward. It’s this raw authenticity, guided by Hou, that makes their mundane struggles – finding work, dealing with loneliness, witnessing the harsh realities faced by others – feel so compelling.

### The Patient Eye of a Master Emerging

This film marks a crucial point in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s trajectory, solidifying the signature style that would define his work and influence a generation of filmmakers. Collaborating closely with writer Chu Tʽien-wen (who would become his essential partner), Hou employs long takes and often static camera positions, allowing scenes to unfold with a natural rhythm. There’s a deliberate avoidance of conventional dramatic punctuation; moments of violence or emotional upheaval are often observed from a distance, integrated into the fabric of everyday life rather than highlighted for effect. This observational approach creates a powerful sense of place, where the environment – the windswept landscapes of Fengkuei, the noisy factories and cramped apartments of Kaohsiung – becomes almost a character in itself, shaping the lives unfolding within it.

It's fascinating to know that Hou himself had a similar experience, moving from the county of Fengshan to Taipei, lending the film a palpable layer of personal resonance. He reportedly struggled to secure funding for The Boys from Fengkuei, finding support outside the established studio system. This independence perhaps allowed him the freedom to pursue this more personal, less commercially driven style, marking a significant break from the dominant melodramas and kung fu flicks of earlier Taiwanese cinema and helping usher in the Taiwanese New Wave alongside contemporaries like Edward Yang. The result is a film that feels handcrafted, imbued with a quiet integrity.

### Lingering Echoes of Youth

Rewatching The Boys from Fengkuei today, nestled amongst our memories of more bombastic 80s fare, offers a different kind of nostalgic journey. It taps into that universal feeling of being young, restless, and uncertain about what comes next. It doesn't offer easy answers or neat resolutions. Instead, it captures the melancholic beauty of transition, the bittersweet ache of leaving childhood behind, and the quiet anxieties that accompany stepping into an unknown future. Doesn't that feeling, in some way, echo through our own recollections of growing up? The film asks us to simply watch, to feel the passage of time alongside these characters, and to recognise the small, often unspoken moments that mark significant internal shifts.

It’s a film whose power lies in its subtlety, its refusal to impose meaning, allowing it to seep into your consciousness slowly. It might not have been the tape you reached for every Friday night at the video store, but its quiet observation and profound empathy make it a vital piece of 80s world cinema, a haunting portrait of youth caught in the currents of change.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful, emerging directorial vision, its deeply authentic performances that capture the nuances of youthful drift, and its historical significance as a key work of the Taiwanese New Wave. Its patient, observational style creates a uniquely immersive and resonant atmosphere, even if its deliberate pace might test viewers accustomed to faster narratives. The Boys from Fengkuei doesn't just depict a transition; it feels like one, leaving you with the lingering image of horizons shifting, both on screen and perhaps, in retrospect, within ourselves.