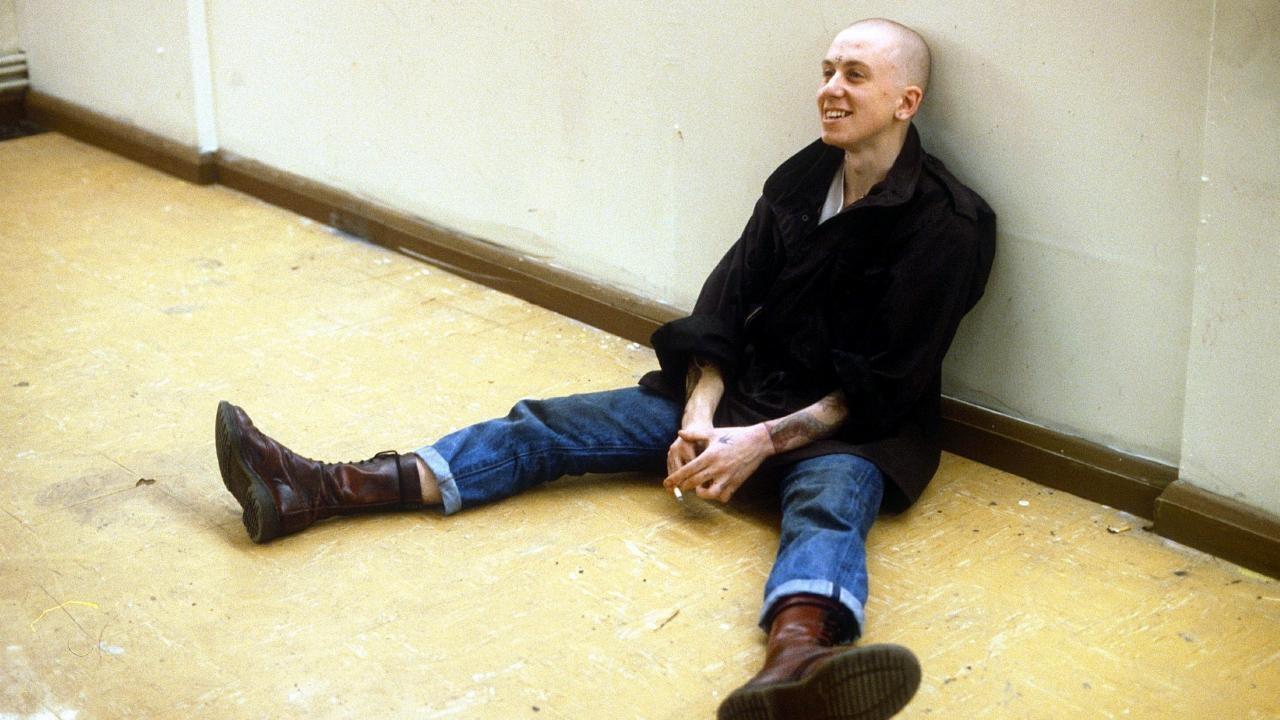

It’s the face you remember first, isn't it? That tight knot of adolescent fury, the simmering resentment barely contained behind narrowed eyes, the shaved head already a defiant symbol before he even opens his mouth. Watching Tim Roth unleash Trevor onto the screen in Alan Clarke's 1982 television film Made in Britain is less like watching a performance and more like witnessing an elemental force being barely contained. Even now, revisiting it decades later, the film retains an astonishing, uncomfortable power.

A Portrait Etched in Anger

This wasn't your typical troubled youth drama, even for the gritty realism often found in British television of the era. Written by David Leland (who would later explore similar themes in his own directorial work like Wish You Were Here (1987)), Made in Britain offers little in the way of easy answers or comforting redemption arcs. Trevor isn't just misguided; he's intelligent, articulate, and utterly, chillingly committed to his own path of nihilistic self-destruction. Roth, in his electrifying screen debut – apparently cast after Alan Clarke saw his raw energy during auditions – embodies this completely. He makes Trevor charismatic in his own caustic way, forcing us to lean in even as we recoil. You understand why people might initially try to reach him, but you also see the brick wall he throws up, plastered with racist epithets and a profound 'f*** you' to the world. It’s a performance of startling authenticity, devoid of actorly vanity, capturing the volatile cocktail of boredom, intelligence, and rage that defines Trevor.

Clarke's Uncompromising Lens

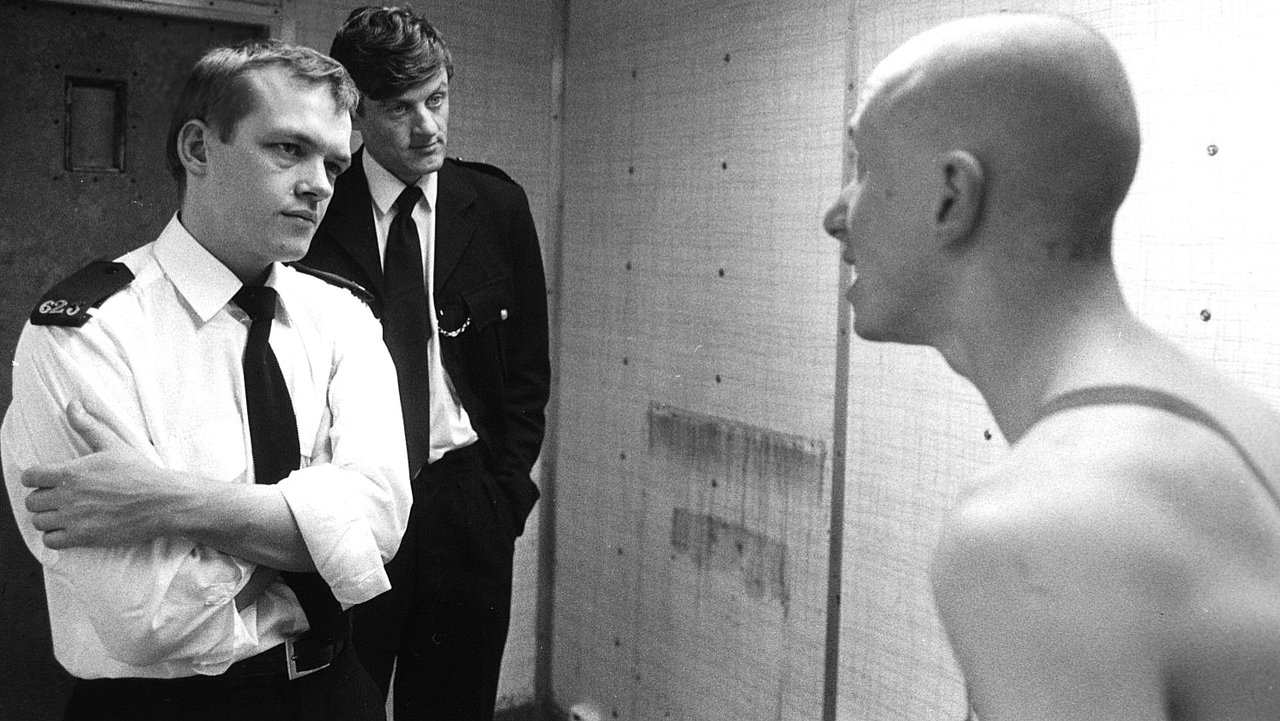

Alan Clarke was a master of depicting uncomfortable truths, often focusing on marginalized figures and systemic failures (his earlier, brutal borstal drama Scum (1979) is perhaps the most famous example). His signature style is fully evident here. The camera, often a fluid Steadicam, follows Trevor relentlessly, sometimes walking just behind him, sometimes confronting him head-on. There's little stylistic flourish, minimal non-diegetic music, and long, observational takes that force the viewer to inhabit Trevor's hostile world. Clarke refuses to judge or explain Trevor away with simple sociological reasoning. He simply presents him, forcing us to confront the reality of his existence within the institutional settings – assessment centres, job interviews, police stations – that utterly fail to connect with or contain him. It’s this unflinching approach that made the film so potent when it first aired (after some initial controversy and delay, reportedly being pulled from the Play for Today slot it was intended for) and gives it its lasting impact. It felt dangerously real, beamed directly into living rooms across the UK.

Echoes of an Era

Watching Made in Britain now inevitably evokes the backdrop of early 1980s Britain under Thatcher: rising unemployment, social unrest, and a widening gap between the establishment and those left behind. Trevor’s racism and destructive tendencies aren't excused, but they are contextualized within a society that seems to offer him nothing but dead ends and authority figures (like the well-meaning but ultimately powerless social worker played by Terry Richards, or the more cynical officials) who speak a language he refuses to understand. The film doesn't preach; it observes, presenting a microcosm of societal breakdown through one individual's implacable resistance. It’s a bleak picture, questioning the effectiveness of the systems designed to manage dissent and reform youth. What happens when someone is intelligent enough to see through the system but lacks any incentive to participate in it?

Trivia Tidbit: The Walk Alan Clarke became renowned for his 'walking shots', often long Steadicam sequences following characters through their environments. Made in Britain features several prime examples, immersing the viewer in Trevor's restless energy and his navigation of often oppressive institutional spaces. It became a visual shorthand for Clarke's raw, observational style.

The Lingering Discomfort

(Minor Spoiler Warning for the film's ending)

The film culminates not in resolution, but in a moment of stark, brutal finality that offers no easy catharsis. Trevor's ultimate act of defiance is both shocking and, in the grim logic of the film, almost inevitable. It leaves you with a pit in your stomach, a sense of waste, and difficult questions about responsibility – individual and societal. There’s no tidy moral, no hopeful glimmer. Just the cold reality of a path chosen, and its devastating consequences.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's raw, undeniable power, anchored by one of the most astonishing debut performances in British cinema history from Tim Roth. Alan Clarke's direction is masterful in its stark realism, creating an uncomfortable but essential piece of social commentary. It’s not an easy watch, lacking the comforting narrative arcs many films provide, but its unflinching honesty and the haunting portrayal of alienated youth make it unforgettable. It earns its high score through sheer impact and artistic integrity, perfectly capturing a specific moment of societal tension with enduring relevance.

Made in Britain is a reminder of how potent and provocative television drama could be, a Molotov cocktail thrown into the living room. It’s a film that doesn't fade easily after the credits roll, leaving you pondering the face of anger and the systems that struggle, and often fail, to contain it. What endures most is perhaps Trevor’s unwavering stare – a challenge, a void, a reflection of something broken that we still haven’t entirely figured out how to fix.