There’s a certain kind of chill that settles in the air when technology breathes where it shouldn’t, when the line between creation and resurrection blurs into something deeply unnatural. It’s the chill that permeates Wes Craven’s 1986 oddity, Deadly Friend. Not the visceral terror of Freddy Krueger invading dreams, but a colder, more mechanical dread wrapped in suburban pleasantries, like finding rust creeping beneath fresh paint. This wasn't just another slasher; it was something... stranger, stitched together from parts that never quite seemed to belong.

Boy Genius, Loyal Bot, Girl Next Door

We meet Paul Conway (Matthew Labyorteaux, familiar to many from Little House on the Prairie), a whip-smart teenager who arrives in a new town with his mother and his best friend, BB – a charmingly clunky, yellow robot of his own design. Paul is earnest, brilliant, maybe a little naive. He quickly falls for the literal girl next door, Samantha (Kristy Swanson, years before staking vampires in Buffy the Vampire Slayer). Their budding romance feels sweet, almost like an Amblin-esque escape, contrasting sharply with the darkness simmering in Sam's own home thanks to her abusive, alcoholic father. There's an innocent, almost Spielbergian vibe initially, centered around Paul's technical wizardry and BB's endearing personality (achieved through some impressive practical puppetry and radio control work for the era). You settle in, thinking you know the path this 80s sci-fi tale will tread. You'd be wrong.

Where Science Meets Grief (and Studio Notes)

The heart of Deadly Friend is a collision – not just of genres, but of visions. Based on Diana Henstell's novel "Friend," the original concept, crafted by Craven and Bruce Joel Rubin (who would later pen the ethereal Ghost and the psychological nightmare Jacob's Ladder), leaned more towards a tragic sci-fi romance, exploring grief, loss, and the ethical quagmire of playing God. When tragedy strikes and Sam is left brain-dead after a violent encounter with her father, Paul, driven by desperate love and misguided genius, implants BB's salvaged microchip processor into her brain. It's a premise ripe with unsettling potential, exploring the uncanny valley where humanity is mimicked but not truly present.

However, this wasn't the film audiences, or more accurately, Warner Bros., wanted from the man who gave them A Nightmare on Elm Street just two years prior. Test screenings were reportedly cold; audiences craved the Craven they knew – the master of visceral shocks and nightmare logic. The studio demanded reshoots, injecting graphic violence and jarring horror sequences that feel awkwardly grafted onto the film's chassis. This behind-the-scenes tug-of-war is palpable on screen. You can almost feel the gears grinding as the film lurches between sensitive character moments, dark sci-fi pondering, and sudden bursts of over-the-top gore. It’s fascinating trivia that transforms the viewing experience, explaining why the film feels so tonally schizophrenic. It wasn't just inconsistent; it was actively reshaped against its creators' initial intent.

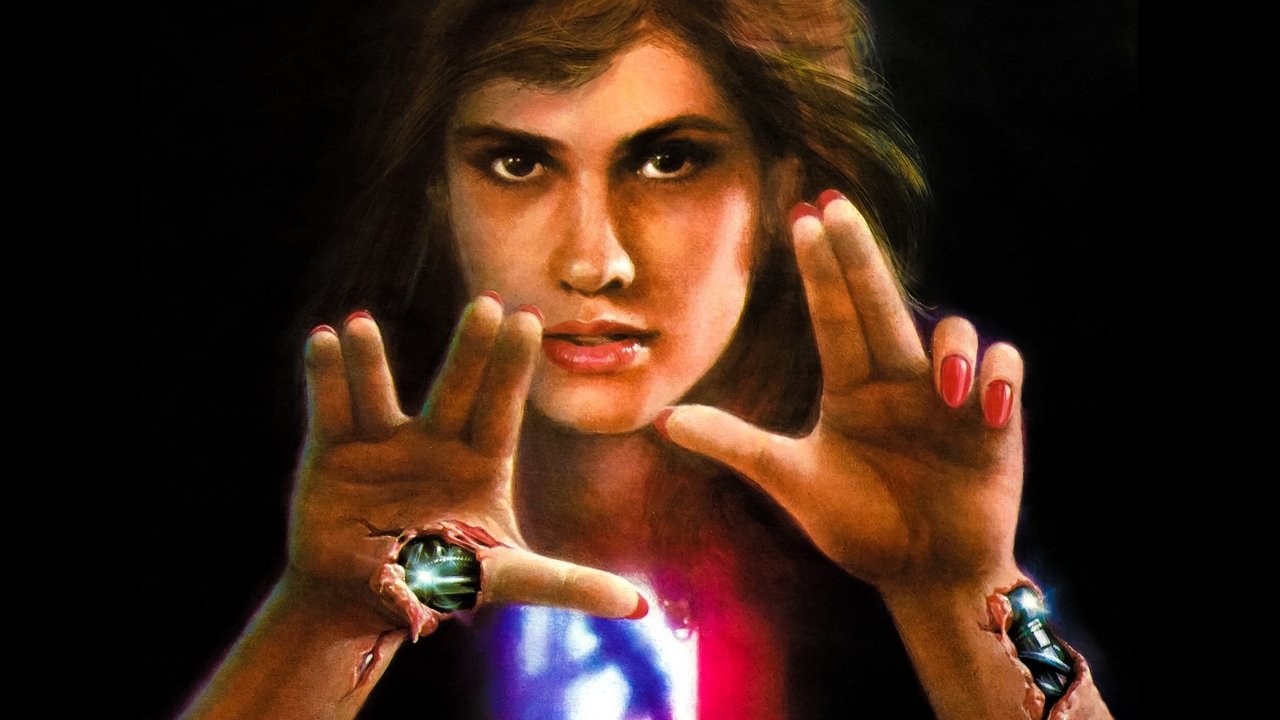

The Uncanny Return and That Infamous Scene

When Sam returns, Kristy Swanson delivers a performance that’s genuinely unnerving. Her movements are stiff, robotic, her face an eerie mask cycling through programmed expressions. She’s strong, fast, and utterly devoid of the warmth she once had. This revived Sam is a walking embodiment of the film's fractured identity – part tragic victim, part technological terror. The practical effects used to depict her increasing decay and robotic strength are classic 80s fare, sometimes gruesome, sometimes endearingly clunky, but always memorable.

And then there’s that scene. Yes, the basketball scene. If you’ve seen Deadly Friend, you know the one. It involves Sam, an annoying neighborhood hag (Anne Twomey as Elvira Parker), and a basketball used in a way Spalding never intended. It’s so outrageously violent, so tonally jarring, it snaps you right out of the film’s more thoughtful moments. Reportedly one of the sequences mandated by the studio, it's become the film's most infamous legacy – a moment of pure schlock horror absurdity that feels both wildly out of place and undeniably memorable. Did it genuinely shock you back then, or just make you stare in disbelief? For many who grabbed this tape off the rental shelf, perhaps enticed by Craven’s name and the intriguing cover art, this scene alone cemented its cult status. Similarly, the tacked-on, final jump scare ending feels like pure studio mandate, a desperate attempt to provide one last Craven-esque jolt that undermines any lingering thematic resonance.

A Broken Toy with Lingering Charm

Despite its troubled production and uneven nature, Deadly Friend holds a strange fascination. Charles Bernstein’s score tries its best to bridge the gaps, sometimes achieving a melancholic, synthesized eeriness, other times leaning into standard horror cues. The suburban setting, usually a symbol of safety, becomes claustrophobic and threatening. There’s a genuine sadness at the core of the story – Paul’s hubris born of love, Sam’s stolen life replaced by a cold imitation. It’s a film constantly at war with itself, a sci-fi tragedy forcibly mutated into a horror spectacle.

I remember renting this back in the day, the stark image on the VHS box promising something dark and different from Wes Craven. It was different, just not entirely in the way one expected. It felt like a puzzle with pieces from different boxes, intriguing but never quite fitting together perfectly. Yet, there's an undeniable charm to its B-movie sensibilities, its practical effects, and the sheer audacity of its infamous gore moments. It’s a film whose making-of story is arguably as compelling as the film itself.

Rating & Final Thought

6/10 - Deadly Friend is undeniably flawed, a film visibly scarred by studio interference that mangled its original, more thoughtful sci-fi concept. Its tonal shifts are jarring, and some moments dive headfirst into absurdity. Yet, it’s also strangely compelling, featuring unnerving practical effects, a committed performance from Kristy Swanson as the resurrected Sam, and that unforgettable basketball scene. Its troubled production history adds a fascinating layer, making it a unique, if fractured, entry in Wes Craven’s filmography and a bona fide 80s cult curiosity perfect for a nostalgic deep dive.

It stands as a potent reminder from the VHS era that sometimes, the most interesting monsters aren't just on screen, but lurking in the memos between director and studio.