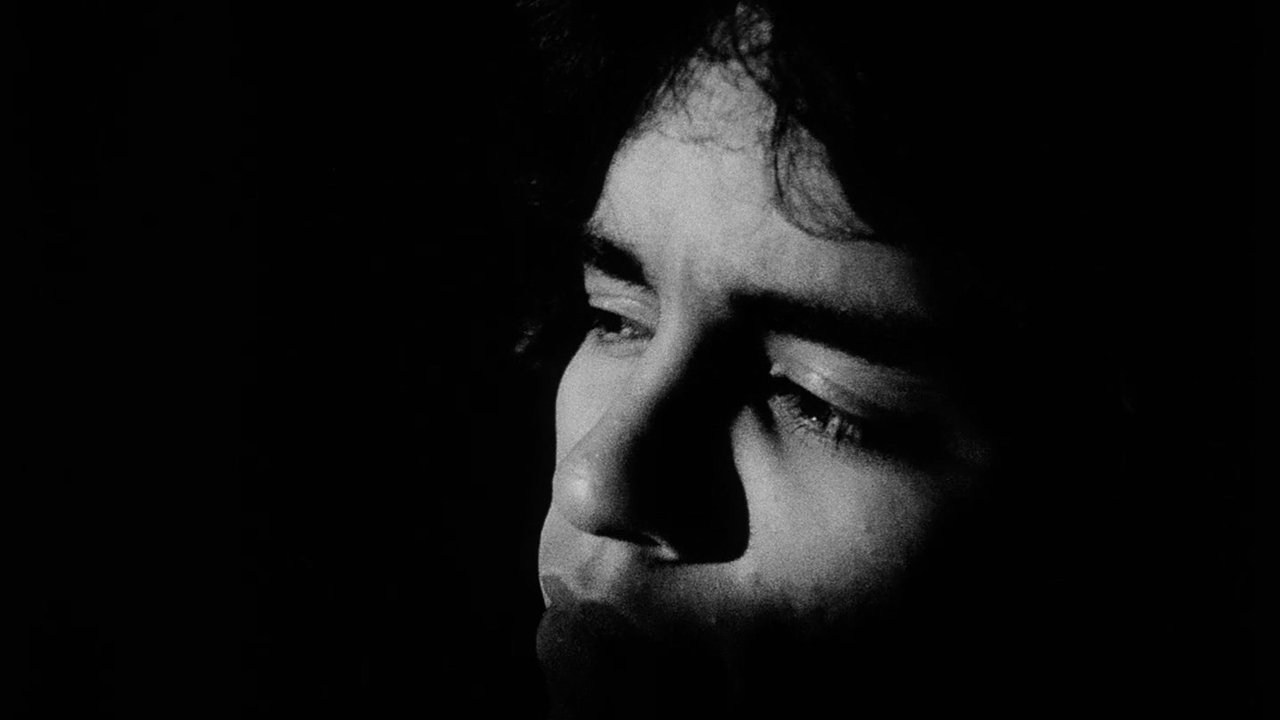

There's a certain grain, a texture you only get from low-budget 16mm film shot with palpable urgency, that feels almost like forbidden memory. Watching Gus Van Sant's debut feature, Mala Noche (1986), is like uncovering such a memory – raw, unflinching, steeped in the damp grey twilight of Portland, Oregon. It doesn't gently invite you in; it confronts you with a stark portrait of yearning that borders on the abrasive, a world away from the neon glow often associated with mid-80s cinema. Forget slick narratives; this is cinema verité bleeding into poetic desperation.

A Glimmer in the Grit

The premise is deceptively simple: Walt (Tim Streeter), a sensitive, somewhat naive convenience store clerk, becomes instantly and overwhelmingly infatuated with Johnny (Doug Cooeyate), a young, undocumented Mexican immigrant who barely speaks English. Walt's desire isn't depicted as romantic longing but as a consuming, often clumsy, and ethically murky obsession. He pursues Johnny relentlessly, offering money, food, and shelter, his intentions blurred between genuine affection and a desperate need for connection, however transactional it might seem. Johnny, along with his friend Pepper (Ray Monge), exists in a state of precarious survival, navigating poverty and displacement, viewing Walt with a mixture of amusement, suspicion, and opportunism. Van Sant, adapting Walt Curtis's autobiographical novella, refuses to smooth the rough edges.

Forging a Path with Loose Change

What immediately strikes you is the film’s stark aesthetic. Shot in moody black and white, the Portland cityscape feels less like a backdrop and more like a character itself – dilapidated, rain-slicked, imbued with a melancholic beauty. This wasn't an artistic choice born from abundance. Van Sant famously scraped together the film's meager $25,000 budget mostly from savings earned directing television commercials back East. This shoestring reality permeates the film's DNA, contributing to its almost documentary-like immediacy. You feel the chill in the air, the grime on the streets. It’s a powerful reminder that sometimes limitations breed incredible artistic focus. This wasn't just Van Sant finding his voice; it was him shouting it from the rooftops with whatever resources he could muster, creating an early, vital piece of what would become known as New Queer Cinema.

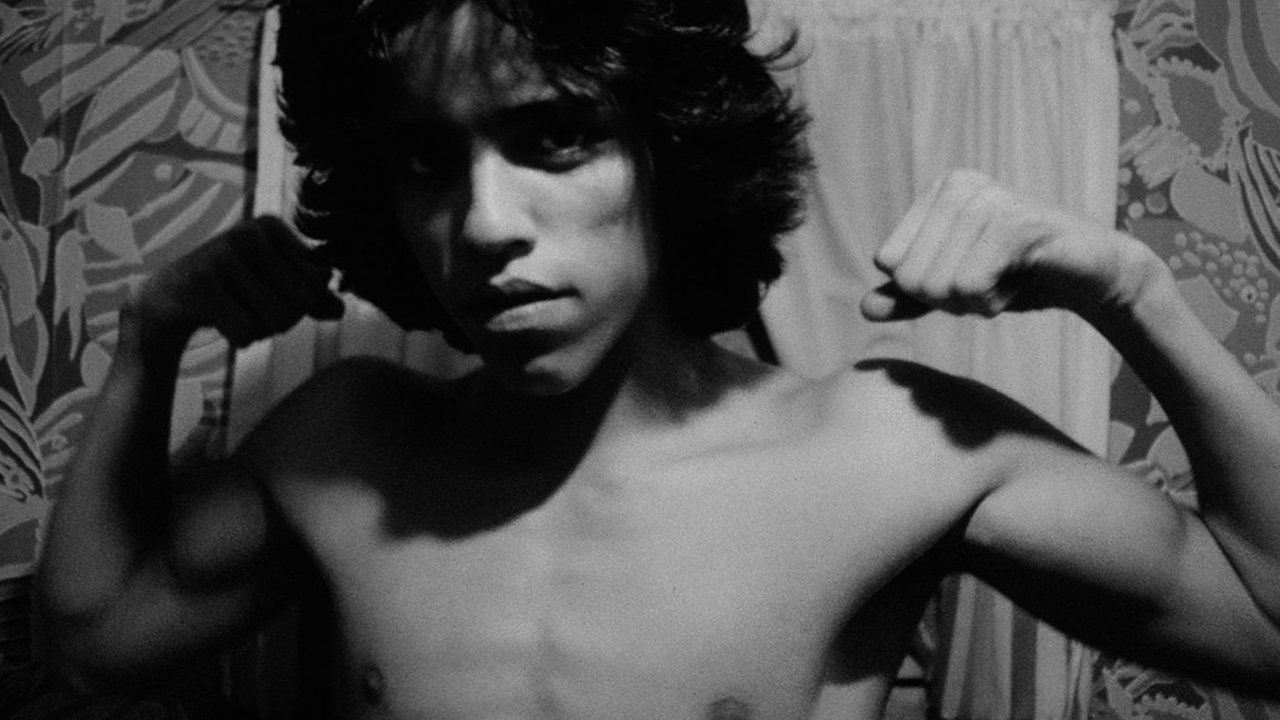

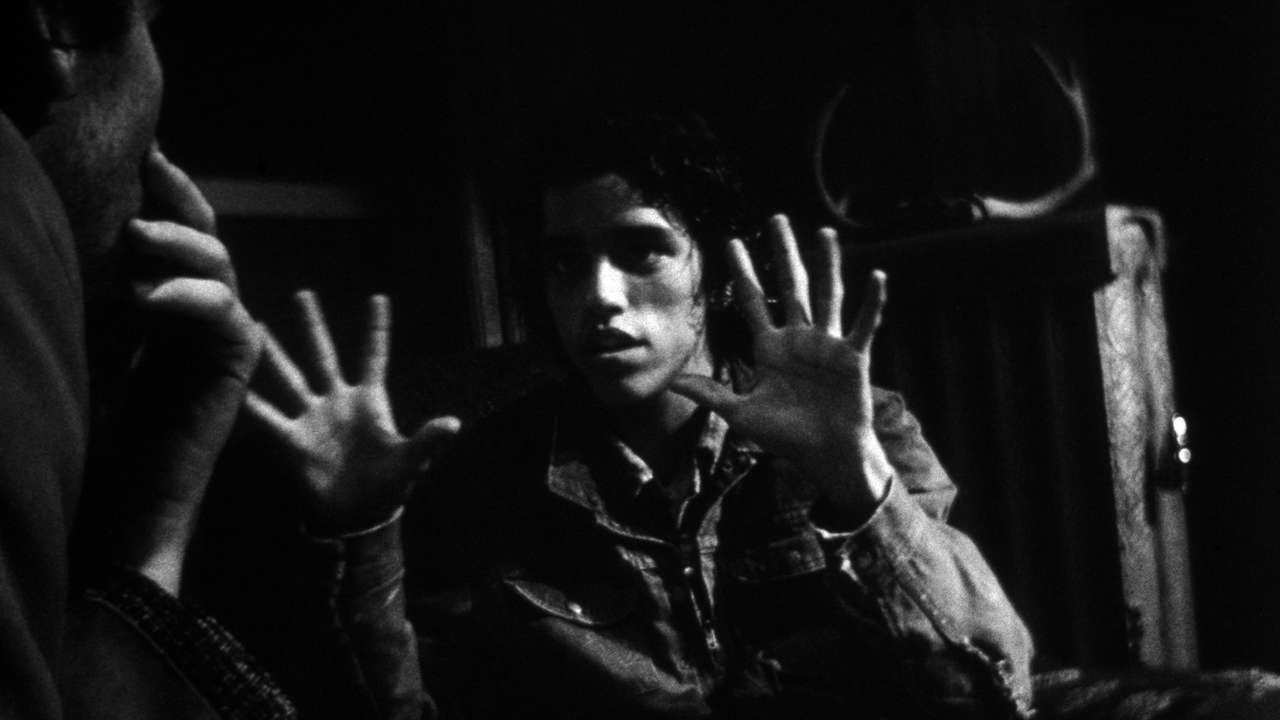

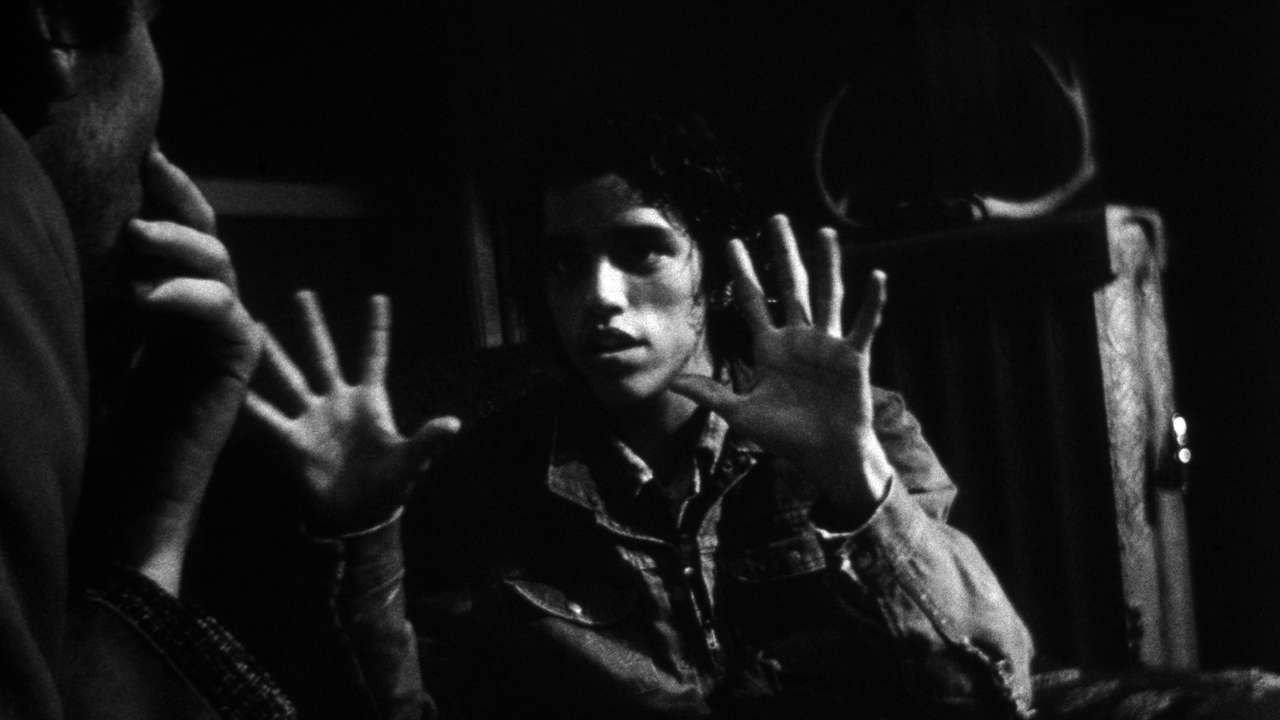

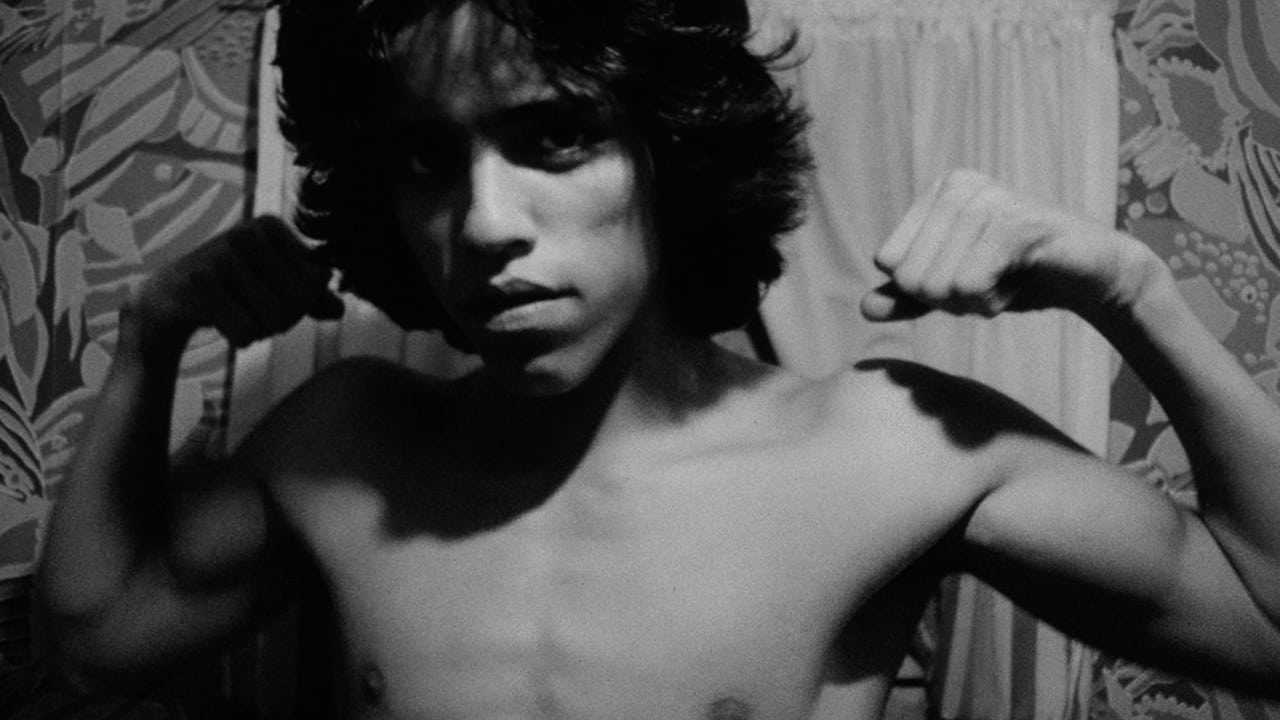

Truth in Untrained Faces

Much of Mala Noche's raw power comes from its performances, particularly their lack of polish. Tim Streeter, a local Portland figure rather than a seasoned actor, embodies Walt with a startling vulnerability. His gaze holds both hope and a deep-seated loneliness; his pursuit of Johnny feels less predatory than deeply, painfully human in its flawed desperation. You might not always root for Walt, but Streeter makes you understand the ache driving him. The real masterstroke, though, was Van Sant's casting of Doug Cooeyate and Ray Monge. These weren't actors playing immigrants; they were young men navigating circumstances similar to their characters. Their performances possess an unvarnished authenticity that scripted portrayals often miss. Their interactions with Walt, shifting between guardedness and fleeting connection, feel utterly real because, in many ways, they were. It's a casting choice that underlines the film's exploration of cultural divides and the inherent difficulties of communication across them. And in a delightful touch of meta-commentary, the novella's author, Walt Curtis, actually appears in the film as George, a character who lends Walt money – a direct link between the source and its stark adaptation.

Beyond the Surface Longing

Mala Noche isn't just about unrequited love. It delves into the complexities of power dynamics, the subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways needs are exploited on both sides of the equation, and the profound isolation that can exist even in moments of attempted intimacy. Van Sant doesn't offer easy answers or moral judgments. He simply presents the situation, forcing the viewer to grapple with the uncomfortable truths simmering beneath the surface. The title, translating to "Bad Night," feels apt not just for specific events, but for the overarching sense of unease and nocturnal searching that defines Walt's journey. This film felt like contraband when glimpsed on a worn VHS tape back in the day, something miles removed from the multiplex, whispering truths about lives lived in the margins. It wasn't aiming for broad appeal; it demanded attention through its sheer, unadorned honesty.

The Seed of a Style

Watching Mala Noche today, you can clearly see the seeds of Van Sant's later, more famous works like Drugstore Cowboy (1989) and My Own Private Idaho (1991). The observational style, the focus on marginalized characters, the evocative use of location, the blend of poeticism and grit – it's all here in nascent form. Initially struggling to find distribution, the film slowly built a reputation on the festival circuit and through word-of-mouth, eventually securing its place as a vital piece of American independent filmmaking from the 80s. It’s a testament to the power of a singular vision pursued against the odds.

***

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: Mala Noche earns its high score through its uncompromising artistic vision and raw authenticity. Despite its micro-budget limitations (or perhaps because of them), Van Sant crafts a film that is visually striking and emotionally resonant, even if unsettling. The performances, particularly from the non-professional actors, feel startlingly real, anchoring the exploration of complex themes like obsession, cultural barriers, and exploitation. While its pacing and raw aesthetic might challenge some viewers, its historical significance as Van Sant's debut and a key work of early New Queer Cinema, combined with its lasting atmospheric power and thematic depth, make it a compelling and important piece of 80s independent film history. It’s not polished, but its rough edges are precisely where its truth resides.

Final Thought: Long after the static fades, what lingers from Mala Noche isn't a neat story, but the damp chill of Portland streets and the persistent, uncomfortable ache of human longing stripped bare.