The flicker begins, not just from the aging magnetic tape, but from the screen itself. Crimson light bleeds across a sterile university laboratory, illuminating young faces taut with ambition and a terrifying curiosity. A stopwatch ticks with agonizing precision. The question hangs heavy in the chilled air, thick with ozone and formaldehyde: what waits for us beyond the flatline? This isn't just another medical drama; this is the unsettling precipice explored in Joel Schumacher's 1990 psychological thriller, Flatliners. A film that felt less like science fiction and more like a dare whispered in the dark.

The Siren Song of the Other Side

The premise alone possesses a chilling simplicity. A group of hyper-competitive, ethically dubious medical students decides to push the ultimate boundary. Led by the driven, almost messianic Nelson Wright (Kiefer Sutherland, radiating intensity hot off Young Guns), they conspire to induce temporary clinical death – flatlining – experience whatever lies beyond, and then be resuscitated by their peers. Nelson goes first, followed by the guilt-ridden Rachel Manus (Julia Roberts, in a role showcasing dramatic depth alongside her burgeoning Pretty Woman superstardom), the pragmatic but increasingly unnerved David Labraccio (Kevin Bacon, ever the grounded counterpoint), the womanizing Joe Hurley (William Baldwin), and the meticulous documentarian Randy Steckle (Oliver Platt). What starts as a quest for forbidden knowledge quickly spirals into a confrontation with something far more personal and terrifying: their own past sins.

Visions in Vivid Hellscapes

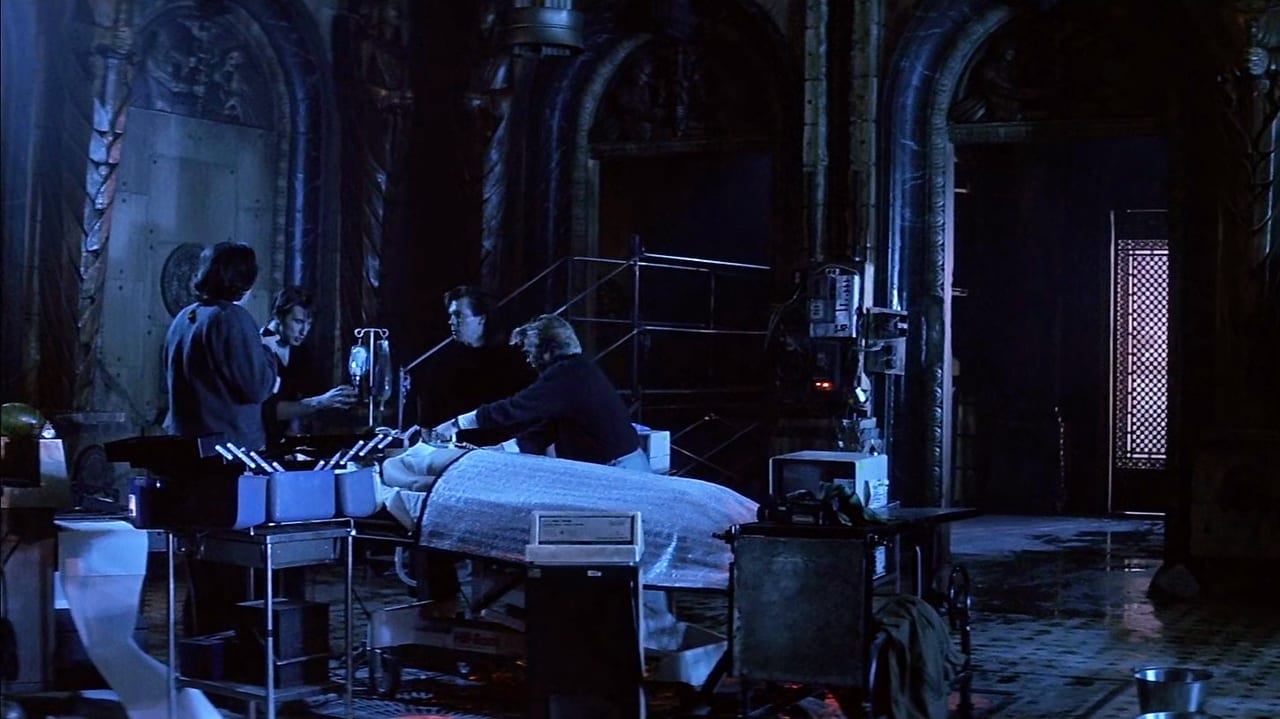

Schumacher, who’d already proven his mastery of atmospheric visuals with The Lost Boys (1987), crafts a distinct aesthetic divide here. The 'real' world is often draped in cool blues and sterile whites, the sterile environment of medicine and academia. But the near-death experiences? They explode with hyper-saturated, often nightmarish colour palettes, courtesy of cinematographer Jan de Bont (who would later helm blockbusters like Speed). Nelson’s afterlife is a landscape of wind-swept trees and ghostly figures bathed in unsettling autumnal light; Rachel confronts traumatic memories under sickly, oppressive hues. These sequences aren't just jump scares; they are deeply psychological, tapping into primal fears of unresolved guilt and inescapable consequence. The production design leans into a slightly gothic sensibility, turning university halls and rooftops into shadowy stages for confrontation. Filming on location at real Chicago campuses like Loyola University certainly grounded the fantastic premise, making the eventual intrusions of the supernatural feel all the more jarring.

When the Past Refuses to Stay Dead

What elevates Flatliners beyond its high-concept hook is how it literalizes the idea of being haunted by your past. The 'visions' don't stay on the other side. They bleed back into reality, manifesting as physical assaults, spectral taunts, and constant reminders of cruelty, betrayal, and mistakes. Nelson is stalked by the ghost of a boy he bullied decades ago; Rachel is confronted by the memory of her father's suicide; Joe is tormented by the women he secretly filmed. It’s here the film taps into a potent vein of psychological horror. There's a story, perhaps apocryphal but fitting the film's dark aura, that writer Peter Filardi drew inspiration from a friend recounting a near-death experience, lending a chilling edge of possibility to the narrative. The script forces characters to confront their worst selves, suggesting that the only true 'beyond' we need to fear is the one we create through our own actions.

Reportedly, the studio nudged the production towards a slightly more redemptive ending than initially conceived, particularly for Sutherland's character. While the existing ending works, one can't help but wonder about that potentially darker conclusion – a staple rumour for many films of this era, often whispered about in video store aisles. Did Nelson truly earn his peace, or was it a concession? It adds another layer to the film's unsettling ambiguity.

A Constellation of Rising Stars

The ensemble cast is undeniably one of the film's greatest strengths. Sutherland perfectly embodies Nelson’s dangerous charisma and underlying fear. Roberts brings a crucial emotional anchor as Rachel, her vulnerability making her hauntings particularly poignant. Bacon, as ever, provides a relatable anchor, his skepticism slowly eroding into terror. Baldwin and Platt offer necessary, if sometimes less developed, variations on the theme of hubris and consequence. Watching them together, all on the cusp of or newly arrived into major stardom, feels like capturing lightning in a bottle – a moment in time preserved on VHS. Their collective energy fuels the film's momentum, making their shared descent into paranoia utterly believable.

Retro Fun Facts Woven In

- The film's striking visuals weren't without challenges. Achieving the distinct looks for each character's 'afterlife' involved intricate lighting setups and practical effects, pushing the boundaries of what was common for thrillers at the time.

- Budgeted at around $26 million (roughly $60 million today), Flatliners pulled in a solid $61.5 million (about $144 million adjusted) at the box office, proving its high-concept premise connected with audiences seeking thrills beyond traditional horror.

- The atmospheric score by James Newton Howard is crucial, blending electronic pulses with orchestral dread, perfectly complementing the visuals and ratcheting up the tension during the flatlining sequences. Those heart monitor sounds still echo uncomfortably.

The Verdict

Flatliners remains a potent piece of early 90s psychological horror, blending a high-concept sci-fi premise with genuinely unsettling explorations of guilt and consequence. Its visual style is striking, the ensemble cast is electric, and the core idea possesses an enduring chill. While some moments dip into melodrama typical of the era, the pervasive atmosphere of dread and the strength of its central performances keep it compelling. It asks uncomfortable questions and offers answers steeped in moody, gothic visuals rather than easy reassurances. I distinctly remember the palpable tension in the room watching this late at night on a rented tape, the grainy picture somehow enhancing the otherworldliness of the afterlife sequences. Doesn't that stylized, almost operatic approach to the near-death visions still feel uniquely unnerving?

Rating: 8/10

Flatliners stands as a stylish, thought-provoking thriller that successfully merged star power with a genuinely creepy concept. It’s a film that reminds us, sometimes vividly, that the most terrifying ghosts are often the ones we carry within ourselves, waiting just beyond the veil for their chance to haunt us. A true standout from the twilight of the VHS era.