There are certain film titles that, even before the opening credits roll, signal you're in for something potent, something designed to provoke. Spike Lee's Jungle Fever (1991) is undeniably one of them. Landing in video stores with that evocative cover art and a title practically humming with controversy, it felt less like a casual Friday night rental and more like an event. You knew, settling onto the couch as the tape whirred in the VCR, that Lee wasn't going to pull any punches. And he didn't.

Beyond the Affair

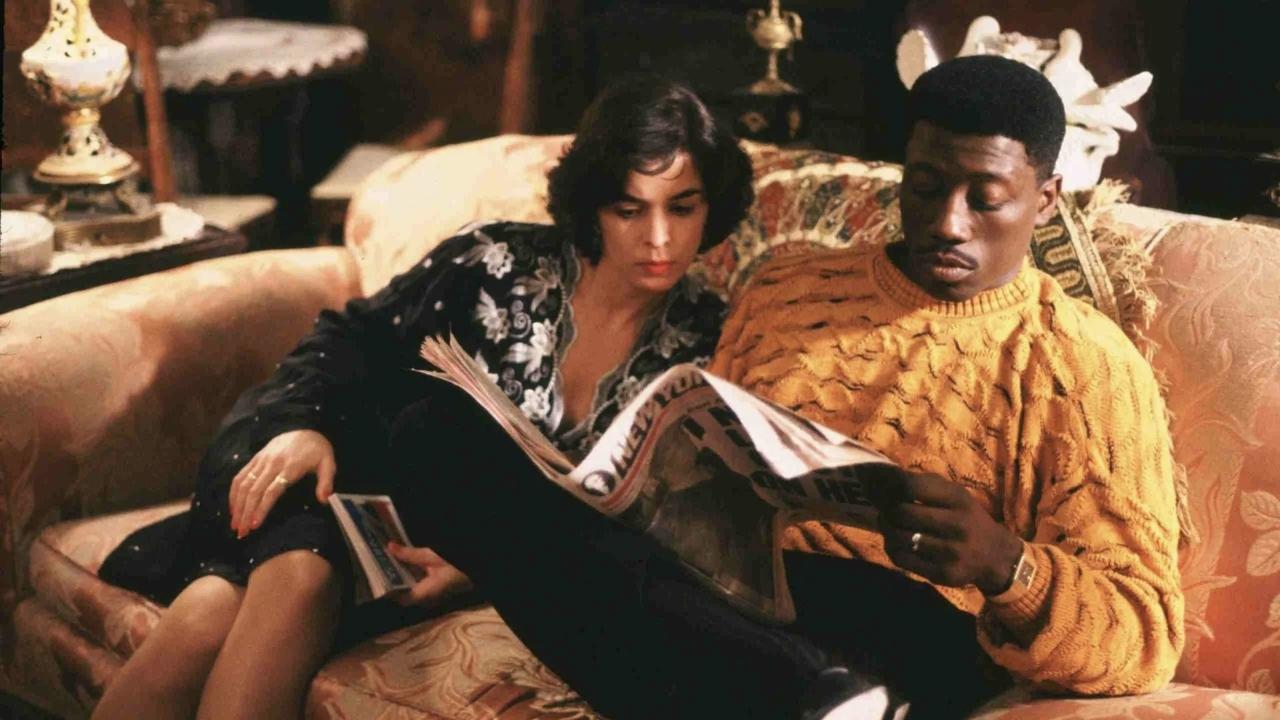

At its core, Jungle Fever explores the fallout of an interracial affair between Flipper Purify (Wesley Snipes), a successful Black architect living in Harlem, and Angie Tucci (Annabella Sciorra), his temporary Italian-American secretary from Bensonhurst. But reducing the film to just that premise misses the sprawling, often messy, and deeply uncomfortable tapestry Lee weaves. This isn't a simple romance challenged by prejudice; it's an autopsy of ingrained biases, societal pressures, and the complex, often contradictory, ways race and class informed life in early 90s New York City.

The film immediately confronts the reasons behind the affair – less about genuine love, perhaps, and more about curiosity, stereotypes, and maybe even a mutual sense of alienation within their own worlds. Flipper, despite his success, faces subtle and overt racism in his predominantly white firm. Angie feels trapped by the expectations of her family and the limited horizons of her neighborhood. Their connection feels almost inevitable, yet Lee refuses to romanticize it. Instead, he focuses on the seismic waves it sends through their respective communities.

Echoes in the Communities

The strength of Jungle Fever lies less in the central couple's dynamic and more in the orbits surrounding them. We see the pain and betrayal etched on the face of Flipper's wife, Drew (Lonette McKee), herself a light-skinned Black woman navigating complex racial politics. We witness the volcanic reactions from Angie's father and brothers, steeped in the tribalism of their Bensonhurst enclave. And perhaps most poignantly, we encounter Flipper's parents, the dignified former preacher The Good Reverend Doctor Purify (Ossie Davis) and his wife Lucinda (Ruby Dee). Their quiet disapproval speaks volumes, grounded in a lifetime of navigating America's racial landscape. The scenes between Snipes, Davis, and Dee are masterclasses in restrained tension and unspoken history. It’s worth remembering that Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, titans of stage and screen, were also married in real life for over 50 years, bringing an incredible depth of shared experience to their roles.

Lee masterfully uses these supporting characters to explore the film's central question: is the relationship doomed not just by external prejudice, but by the internalized biases and mythologies both Flipper and Angie carry? Lee, who also appears as Flipper's friend Cyrus, doesn't offer easy answers. He presents the situation, the raw emotions, the ugliness, and leaves the viewer to grapple with the implications.

Gator's Shadow

While the central story simmers, another narrative thread burns with terrifying intensity: Flipper's brother, Gator (Samuel L. Jackson), a crack addict. Jackson's performance is nothing short of electrifying. It's a raw, visceral portrayal of addiction's grip – the desperate charm, the manipulative pleading, the frightening unpredictability. It's a role that feels utterly authentic, reportedly drawing from Jackson's own struggles around that period. The performance was so powerful it earned him a specially created Best Supporting Actor award at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival – a testament to its undeniable impact. This subplot isn't just tangential; it adds another layer to the family dynamics and the pressures weighing on Flipper, highlighting the devastating impact of the crack epidemic ravaging communities at the time. It also provides some of the film’s most harrowing and unforgettable moments, including Gator's infamous "Wanna Bee" dance. Look closely too for a very early film role for Halle Berry as Gator's fellow addict Vivian – a stark contrast to the glamorous roles that would soon define her career.

A Spike Lee Joint

Visually and sonically, this is pure Spike Lee. The film crackles with the energy of New York City, filmed on location in the distinct neighborhoods of Harlem and Bensonhurst. The tensions simmering in the city at the time are palpable, particularly the Bensonhurst storyline involving Angie's suitor Paulie (John Turturro) and his racist friends, which Lee explicitly linked to the tragic 1989 killing of Yusef Hawkins in that very neighborhood, even dedicating the film to Hawkins' memory.

And then there's the music. Lee commissioned Stevie Wonder to create the entire soundtrack, resulting in iconic tracks like "Jungle Fever" and "Fun Day." Wonder's score isn't just background music; it's an integral part of the film's voice, commenting on the action, amplifying the emotion, and providing moments of both soulful reflection and vibrant energy. Hearing those songs instantly transports you back to that era.

Despite its modest budget (around $14 million, earning back roughly $32 million domestically – respectable numbers for a challenging film then), Jungle Fever felt significant. It tackled themes few mainstream films dared to touch with such directness, sparking conversations and debates that echoed long after the tape was returned to the rental store shelf.

The Verdict

Jungle Fever is not an easy watch, nor is it a perfect film. Some character motivations feel thin, and the central relationship occasionally gets overshadowed by the more potent subplots. Lee’s approach can feel didactic at times, spelling out themes rather than letting them breathe. Yet, its flaws are inseparable from its ambition and its raw, confrontational honesty. It captures a specific moment in time with unflinching clarity, forcing viewers to examine uncomfortable truths about race, class, and attraction that remain relevant today. The performances, particularly from Samuel L. Jackson, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee, are exceptional, anchoring the film's sprawling narrative. It’s a quintessential Spike Lee joint – bold, messy, provocative, and ultimately unforgettable.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable power, its landmark performances (especially Jackson's), and its fearless engagement with difficult themes, even acknowledging its narrative unevenness. It's a vital piece of early 90s cinema that earns its place on the shelf, demanding attention and reflection even decades later. What lingers most isn't the affair itself, but the complex, often painful questions it forces us – and the characters – to confront about the invisible walls we build and the biases we carry.