Okay, tapeheads, gather 'round. Tonight, we're digging out something truly unusual from the back shelves of cinematic memory, a piece that technically lands just outside our usual 80s/90s hunting ground but feels ripped from a much, much earlier era, yet somehow perfect for that late-night, fuzzy-screen discovery. I'm talking about Guy Maddin's electrifying six-minute wonder, The Heart of the World (2000). Found this one tucked away, maybe on a compilation tape someone recorded off a cable channel dedicated to the weird and wonderful, and wow. It’s like unearthing a forgotten Soviet propaganda reel beamed directly into your VCR.

### A Silent Scream in Six Minutes

Right off the bat, The Heart of the World assaults your senses. Forget slow burns; this is cinematic whiplash. Commissioned by the Toronto International Film Festival for its 25th anniversary, Maddin was given a simple, wild brief: create a short film in the style of Soviet Montage cinema, specifically channeling pioneers like Dziga Vertov or Sergei Eisenstein. And boy, did he deliver. The film feels less like a 2000 release and more like a miraculously preserved artifact from the 1920s, complete with hyper-kinetic editing, dramatic intertitles ("SIN!", "STATE!"), and wildly expressive, almost kabuki-like performances.

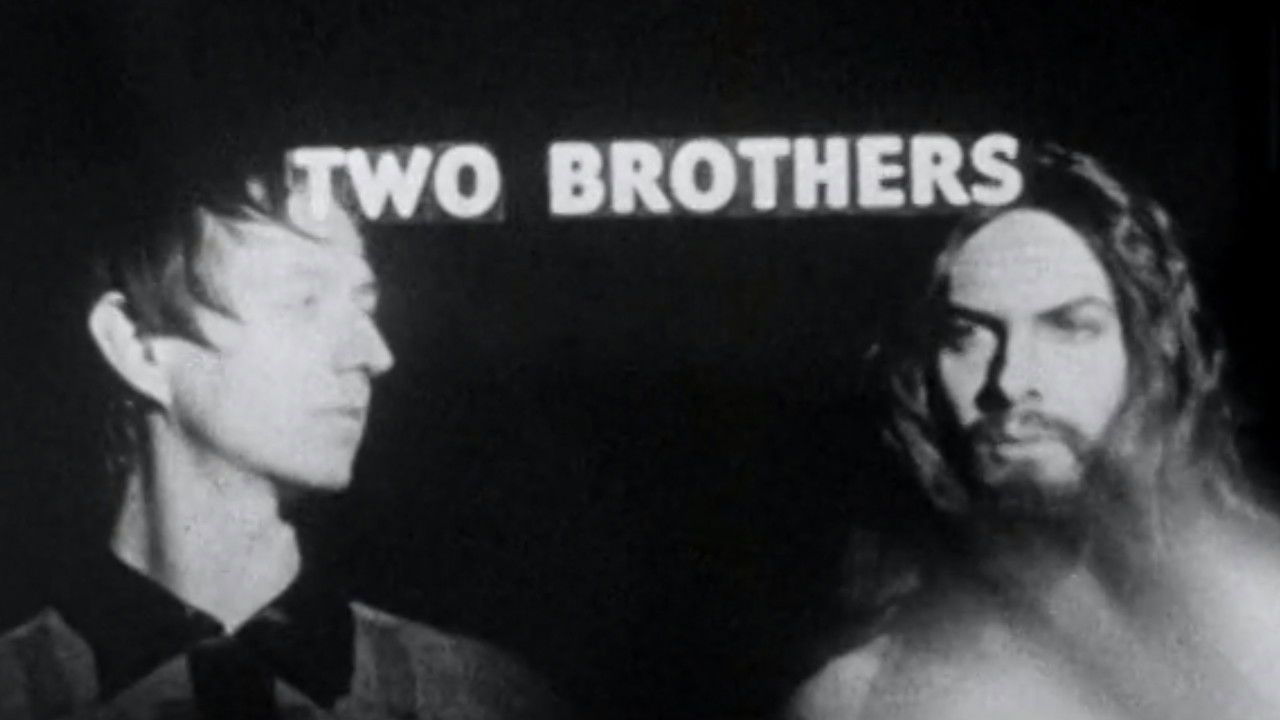

The plot, such as it is, revolves around two brothers vying for the love of Anna (played with wide-eyed intensity by Leslie Bais), a state scientist studying the Earth's failing heart. One brother, Osip (Caelum Vatnsdal), is a noble mortician preparing the dead Christ for burial; the other, Nikolai (Shaun Balbar), is a capitalist actor playing Jesus in a passion play. It’s a frantic allegory crammed with melodrama, industrial decay, romance, and impending doom, all compressed into a runtime shorter than most modern movie trailers. Remember how some action movie trailers back in the day felt like they showed you everything at lightning speed? This feels like that, but it is the entire movie.

### Montage as Action

Now, when we talk "action" at VHS Heaven, we usually mean exploding warehouses and tyre-squealing chases. The Heart of the World offers a different kind of adrenaline rush. The "action" here is pure, uncut montage. Maddin bombards the viewer with images – close-ups of anguished faces, gears grinding, crowds surging, symbolic acts – cut together at breakneck speed. It’s dizzying, overwhelming, and strangely exhilarating. Think of the most frantic sequences in early Oliver Stone films, like Natural Born Killers (1994), but stripped bare of sound (mostly) and cranked up to eleven with silent film aesthetics.

There’s a raw, almost violent energy to the editing that feels incredibly physical, even without traditional stunts. It achieves an intensity through rhythm and juxtaposition that many multi-million dollar blockbusters struggle to match. Maddin uses whip pans, dutch angles, irises, and superimpositions – all classic silent film techniques – to create a sense of chaos and urgency. It’s filmmaking as a breathless sprint, and watching it even now, you can feel the sheer force of its construction. It’s a reminder that cinematic impact doesn’t always require huge budgets or digital trickery; sometimes, it’s just about the power of the cut.

### Retro Roots, Modern Marvel

Part of the charm here is how Maddin embraces the look of old film stock. It’s deliberately distressed, flickering, and high-contrast, mimicking the wear and tear you’d find on ancient nitrate prints. It’s not actual practical effects like fiery explosions, but the commitment to the aesthetic of early, purely mechanical cinema feels incredibly authentic. It was shot quickly and on a tight budget, leaning into limitations to fuel creativity – a spirit many low-budget 80s classics shared. Maddin, who would later give us equally distinctive films like The Saddest Music in the World (2003) and My Winnipeg (2007), proved here he was a master of conjuring entire worlds out of stylistic homage and sheer directorial will.

Interestingly, this short film, initially conceived almost as a gag or a "trailer" for a feature that didn't exist, became a massive critical success. It showed filmmakers and audiences alike the power still residing in seemingly archaic techniques. Watching it feels like discovering a secret history of cinema, a potent shot of pure visual storytelling that cuts right through the noise. It’s the kind of thing you’d stumble upon late at night, maybe flipping channels past midnight, and be utterly mesmerized, wondering what on earth you just saw.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: For its sheer audacity, technical brilliance in replicating a lost style, and packing more cinematic energy into six minutes than most features manage in two hours, The Heart of the World is a near-perfect execution of a unique concept. It's an essential watch for anyone fascinated by film history or just looking for a high-octane visual jolt.

Final Rewind: A frantic, beautiful fever dream from the dawn of the 21st century pretending to be from the dawn of the 20th. It's less a narrative film, more a mainline injection of pure cinema – find it, watch it, and prepare for your pulse to race.