Okay, fellow tapeheads, let’s rewind to a specific kind of weird that only the early 90s, fueled by Japanese manga and practical effects wizardry, could truly deliver. Remember browsing those video store shelves, the fluorescent lights humming overhead, and stumbling across a cover that just screamed what IS this?! Maybe it had a bio-armored warrior battling some grotesque monstrosity. Chances are, you might have landed on 1991’s The Guyver. And if you took that tape home, popped it in the VCR, and adjusted the tracking just right, you were in for… well, you were in for something.

### Bio-Boosted B-Movie Mayhem

Forget intricate plotting; the setup is pure comic book pulp. Hapless college student Sean Barker (Jack Armstrong) accidentally stumbles upon an ancient alien device called "The Unit." This gizmo, looking suspiciously like a discarded piece of sci-fi plumbing, merges with him, allowing him to summon the "Guyver" – a powerful suit of bio-mechanical armor. Naturally, this attracts the attention of the shadowy Chronos Corporation, led by the sneering Fulton Balcus (David Gale, wonderfully slimy), who wants the Unit back to create his army of genetically engineered monsters, the Zoanoids. Cue monster fights, laser beams (sort of), and a healthy dose of that signature early 90s cheese.

Our hero, Sean, played by martial artist Jack Armstrong, is… serviceably wooden. Let's be honest, he’s not why we rented this. He serves his purpose as the bewildered everyman gifted immense power. The real casting coup, and likely the reason many gave this a chance back in the day, is Mark Hamill as CIA agent Max Reed. Fresh off his iconic Star Wars run but before his legendary voice acting career truly exploded, seeing Hamill investigating mutant shenanigans felt both surreal and weirdly perfect. Apparently, Hamill was genuinely a fan of the original Yoshiki Takaya manga, which might explain his earnest presence here, lending a touch of gravitas amidst the rubbery chaos.

### Where the Latex Hits the Road

But let's talk turkey, or rather, Zoanoid. The absolute raison d'être for The Guyver is its creature effects and the Guyver suit itself. This is where the film shifts from standard B-movie fare into something genuinely memorable, especially for fans of practical effects. Co-directed by Screaming Mad George and Steve Wang, both legendary effects artists who cut their teeth on classics like Predator (1987) and A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master (1988), their passion bleeds – sometimes literally – onto the screen.

Remember how tangible those creature suits felt? The glistening latex, the snapping claws, the sheer physicality of the Zoanoid transformations – it wasn't smooth, it wasn't seamless like modern CGI, but it had weight. You could almost smell the rubber cement and KY Jelly. The Guyver suit itself, while perhaps a bit bulky compared to its manga counterpart, looked incredible in action. The transformation sequences, though brief, had that Cronenbergian body-horror tinge that Screaming Mad George, known for his work on the infamous "shunting" scene in Society (1989), excelled at. These weren't just actors in costumes; they felt like living, breathing (and often drooling) monstrosities, thanks to the intricate animatronics and puppetry involved. It's a testament to the artists' skill that they pulled off such ambitious designs on what was reportedly a modest $3 million budget.

The action scenes, while not always choreographed with balletic grace, have a raw, grounded feel. When the Guyver punches a Zoanoid, it feels like two heavy, awkward things colliding. The stunt work, involving performers undoubtedly sweating buckets inside those cumbersome suits, deserves serious props. Compare that to the often weightless feel of purely digital creations today – there’s a charm and impact to this old-school approach that’s hard to replicate. Did every punch connect perfectly? Maybe not. But did it feel like something was really happening on screen? Absolutely.

### Tone, Trivia, and That 90s Vibe

The film does wrestle with its tone. It veers from genuinely creepy creature moments (hello, Michael Berryman as Zoanoid Lisker!) to goofy humour, sometimes within the same scene. This mix didn't always land, contributing to its somewhat lukewarm initial reception from critics. Audiences renting it on VHS, however, often embraced the weirdness. It became a cult favourite precisely because it was a bit uneven, packed with amazing effects but wrapped in a charmingly clunky package. It's a film where one minute you're seeing a truly unsettling monster design, and the next you're getting broad comedy involving inept henchmen.

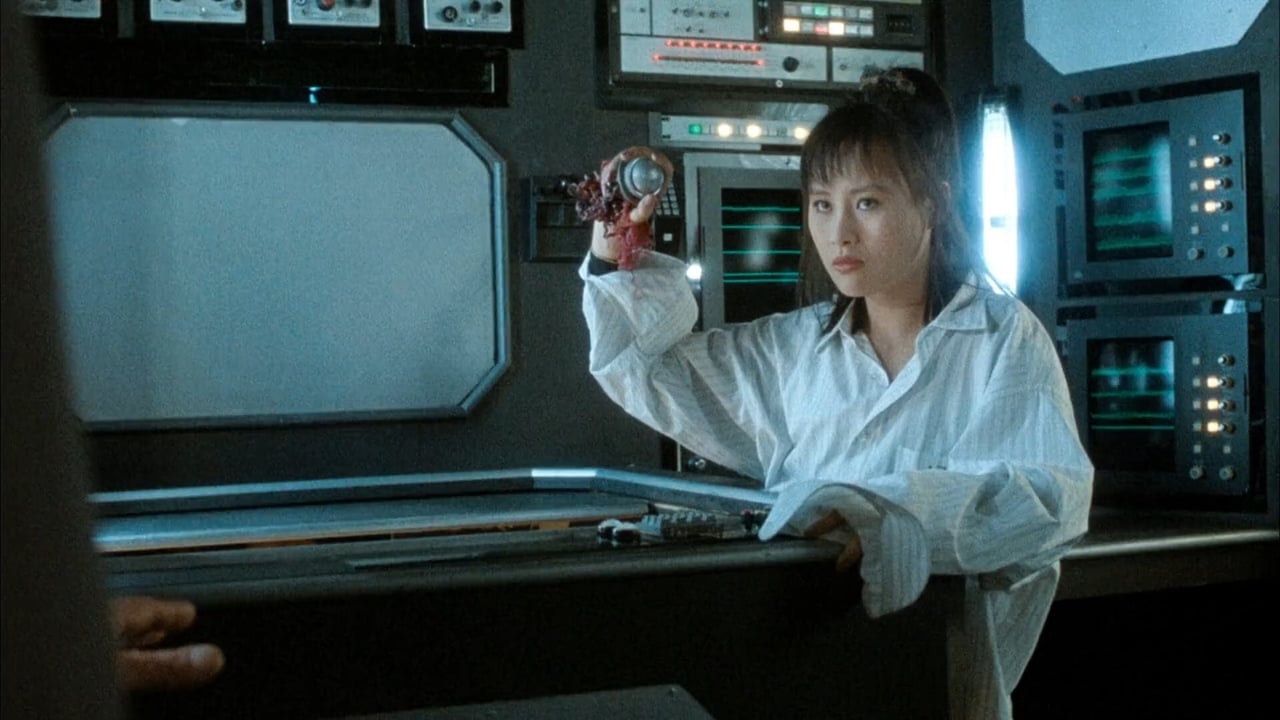

A fun retro tidbit: The challenges weren't just creative. Those elaborate Zoanoid suits were notoriously heavy and hot, making filming physically demanding for the suit performers. It’s that kind of behind-the-scenes struggle, overcoming limitations with practical ingenuity, that defines so much of the era's genre filmmaking we love. You also get Vivian Wu (The Last Emperor, Heaven & Earth) as Mizky, Sean’s love interest, adding another recognizable face to the proceedings.

### Final Verdict

The Guyver isn't high art, and it knows it. It’s a glorious showcase for practical creature effects, a time capsule of early 90s genre filmmaking ambition colliding with B-movie sensibilities. The acting is variable, the script simplistic, and the tone occasionally wobbles. But the sheer creativity and craftsmanship poured into the monsters and the Guyver suit by Wang and George are undeniable and remain impressive today. It paved the way for a darker, arguably superior sequel, Guyver: Dark Hero (1994), but this original holds a special place for its gonzo energy and practical effects heart.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's significant flaws (acting, script, tone) balanced by its exceptional, era-defining practical effects work, its cult appeal, and the sheer fun factor for retro enthusiasts. It's below "great" but well above "bad" for the right audience.

Final Thought: For pure, unadulterated, slimy 90s creature feature goodness fueled by latex and imagination, The Guyver is a VHS treasure – flawed, funky, but undeniably fantastic to look at. It’s the kind of movie that reminds you why practical effects, even when imperfect, felt so wonderfully real.