Okay, settle in, fellow tape travelers. Sometimes, digging through those stacks at the old video store unearthed something unexpected, something that didn't quite fit the flashy box art trends of the early 90s. A film that felt heavier, quieter, etched with a starkness that lingered long after the VCR clicked off. For me, Sean Penn's directorial debut, The Indian Runner (1991), was precisely that kind of discovery. It wasn't heralded by explosions or one-liners, but by the haunting chords of a Bruce Springsteen song.

Echoes of Nebraska

You can almost hear the sparse, melancholic notes of Springsteen's "Highway Patrolman" drifting through this film. Penn didn't just borrow the title of his source material; he captured the very soul of that track from the Nebraska album – a story of two brothers on irrevocably different paths, bound by blood but divided by nature. It’s a bold move for a first-time director, especially one known primarily for his intense, often explosive, on-screen presence. Penn chose not spectacle, but introspection, crafting a story that feels less like a movie and more like a slowly unfolding family tragedy observed through a dusty windowpane.

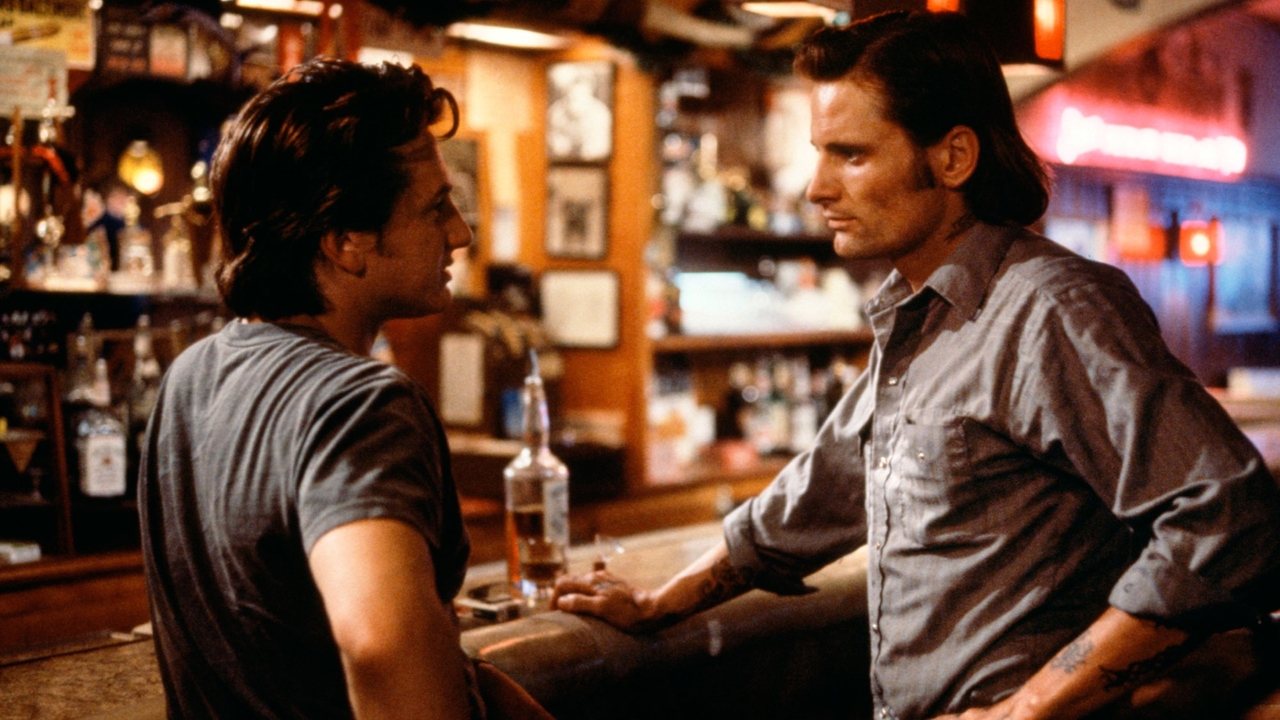

The film introduces us to Joe Roberts (David Morse), a small-town Nebraska deputy sheriff, a man defined by quiet duty and a deep-seated sense of responsibility. He’s the good son, the steady hand, the one trying desperately to hold things together. His world is thrown off its axis by the return of his younger brother, Frank Roberts (Viggo Mortensen), a volatile Vietnam veteran simmering with unprocessed trauma and a dangerous lack of impulse control. The narrative core is this fractured brotherhood: Joe’s attempts to help Frank reintegrate into society, and Frank’s seemingly gravitational pull towards self-destruction.

A Study in Contrasts

The power of The Indian Runner rests heavily on the shoulders of its two leads. David Morse, often a reliable supporting player, absolutely anchors the film with a performance of profound weariness and quiet strength. You see the weight of the world, and specifically the weight of Frank, etched onto his face. He conveys entire histories of concern and frustration with just a look, a sigh. It's a masterful portrayal of stoicism battling against helplessness.

And then there's Viggo Mortensen. This was before Lord of the Rings, of course, but the raw, untamed energy that would later define Aragorn is terrifyingly palpable here, turned inwards and curdled into something destructive. Mortensen embodies Frank’s unpredictability. Is he a victim of his experiences, or simply wired for chaos? The film wisely never gives an easy answer. His charisma is undeniable, drawing people in even as his actions push them away, making his downward spiral all the more agonizing to watch. It's a fearless, live-wire performance that feels utterly authentic, establishing Mortensen early on as an actor of uncommon depth and intensity. Reportedly, Penn and Mortensen forged a strong bond during filming, a connection that likely contributed to the visceral power of Frank's portrayal.

Atmosphere Over Action

Penn, as director, demonstrates a surprising patience and a keen eye for atmosphere. Working with cinematographer Anthony B. Richmond (who shot Don't Look Now (1973) and Candyman (1992)), he paints a picture of late 60s/early 70s rural America that feels lived-in and melancholic. The pacing is deliberate, meditative even, allowing the tension between the brothers, and within Frank himself, to build organically. There are no easy outs, no Hollywood contrivances to soften the blows. Penn seems less interested in plot mechanics than in exploring the emotional landscape of his characters.

It's worth noting this film was made for a relatively modest $7 million. That constraint likely informed its grounded aesthetic – there’s no gloss here, just the grit and grain of ordinary lives grappling with extraordinary internal conflicts. The supporting cast is also stellar, featuring Valeria Golino as Frank’s hopeful wife Maria, Patricia Arquette as a bartender who catches Frank's eye, and brief but impactful appearances by screen veterans Charles Bronson (in one of his final, more dramatic turns) and Dennis Hopper as a philosophical bartender. Each adds another layer to the Roberts brothers' world.

The Weight of Brotherhood

What stays with you after watching The Indian Runner? It’s the intractable nature of the brothers’ dynamic. Can love overcome inherent nature? How much responsibility do we bear for the destructive paths chosen by those we care about? Penn doesn't offer tidy resolutions. The film asks difficult questions about family, violence, masculinity, and the scars left by war, leaving the viewer to grapple with the unsettling ambiguity. I remember renting this on VHS, perhaps drawn by Penn's name or the intriguing cover, and being struck by its quiet intensity – a stark contrast to the louder fare dominating the shelves back then. It wasn't an 'easy' watch, but it felt important.

Despite strong performances and its artistic integrity, The Indian Runner struggled commercially, barely making a dent at the US box office (around $191,000). It perhaps lacked the conventional hooks audiences expected, or maybe its unflinching bleakness was too much for mainstream tastes at the time. Yet, for those who appreciate character-driven drama and nuanced performances, it remains a significant, if somewhat overlooked, piece of early 90s cinema and a potent announcement of Sean Penn's directorial voice.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional performances, particularly from Morse and Mortensen, its powerful thematic depth, and Penn's assured, atmospheric direction in his debut. It's a heavy, somber film, and its deliberate pacing might test some viewers, preventing a higher score, but its emotional honesty and the questions it raises are undeniable.

The Indian Runner is a film that sits with you, a poignant and often painful exploration of bonds that can bind us just as tightly as they can break us. It’s a reminder from the VHS era that sometimes the quietest stories carry the most weight.