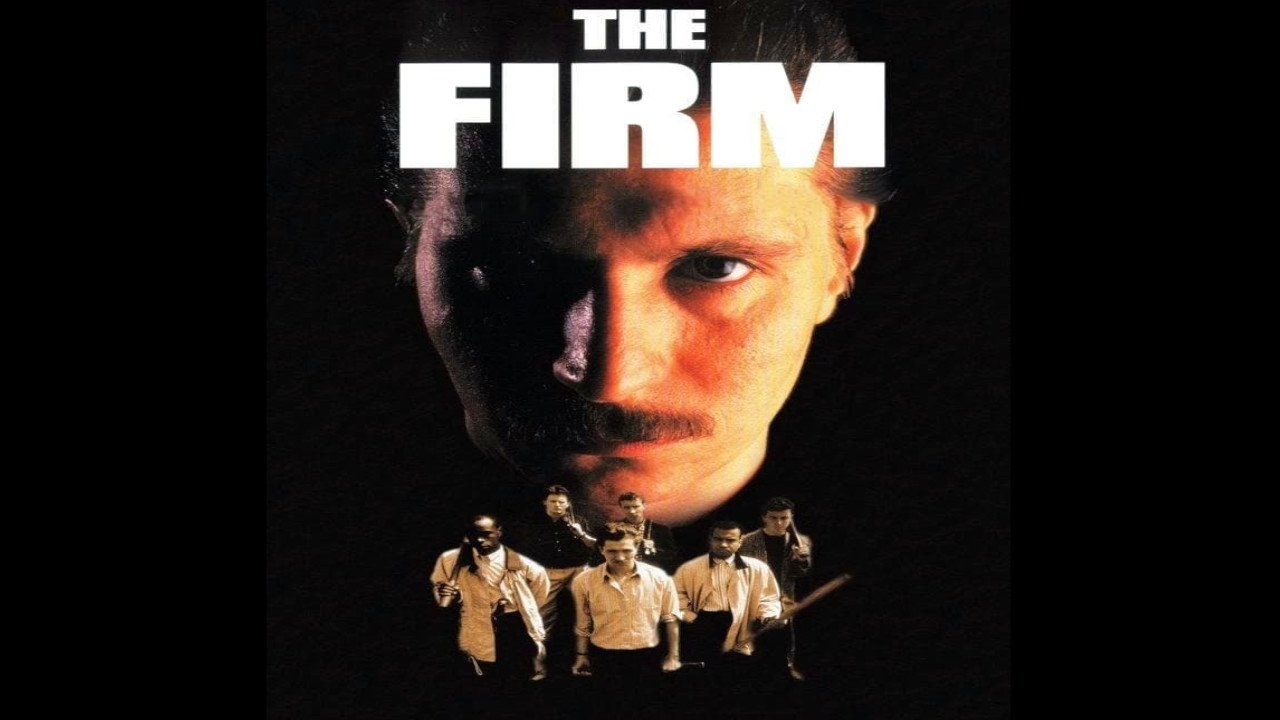

There's an unsettling glint in his eyes, a casual swagger that barely conceals the coiled spring beneath. When Gary Oldman strides onto the screen as Clive Bissel, better known as "Bex", in Alan Clarke's The Firm (1989), you immediately understand this isn't going to be a comfortable watch. Forget romantic notions of terrace chants and club loyalty; this is football hooliganism stripped bare, presented with a chilling lack of judgment that forces you, the viewer, into an uncomfortable reckoning. Originally broadcast as part of the BBC's Screen Two anthology series, this wasn't your typical evening telly. It felt dangerous, illicit almost, like contraband footage smuggled into the living room – a feeling many of us who caught it back then, perhaps on a slightly fuzzy VHS recording, likely remember vividly.

### A Different Kind of Pitch Invasion

The Firm plunges us into the world of rival London football 'firms' preparing for a coordinated clash at the upcoming European Championships. Bex, an outwardly successful estate agent with a young family, is the ambitious leader of the Inter City Crew (ICC). His drive isn't just about defending his patch; it's about forging a unified national 'firm' under his command, a twisted form of patriotism channelled through brutal violence. The plot itself is sparse, focusing less on intricate narrative twists and more on the charged atmosphere, the escalating tensions, and the psychological makeup of the men involved. Clarke, a director renowned for his unflinching social realism (think Scum (1979) or Made in Britain (1982)), employs his signature Steadicam technique to devastating effect. The camera often follows characters, particularly Bex, with a restless intimacy, making us feel like uneasy participants rather than detached observers. There's an immediacy here, a raw, almost documentary feel that amplifies the dread.

### The Banality of Bex

What elevates The Firm beyond a mere exposé is Gary Oldman's truly magnetic and terrifying performance. Fresh off searing roles in films like Sid and Nancy (1986), Oldman embodies Bex not as a simple thug, but as a complex figure driven by ego, insecurity, and a desperate need for status within his chosen tribe. He's chillingly polite one moment, explosively violent the next. The film cleverly contrasts his brutal activities with his aspirational middle-class life – the nice house, the loving wife Sue (Lesley Manville), the baby son. It’s this juxtaposition that’s perhaps most disturbing. How can this seemingly ordinary man, who frets about mortgage rates and polo shirts, orchestrate such savage encounters? It was reported that writer Al Hunter Ashton, drawing on his own past experiences within hooligan culture, wanted to show that these weren't just marginalized youths, but often men with jobs, families, and mortgages – a far more unsettling truth. Oldman nails this duality, the respectable veneer cracking under the pressure of his violent obsession. His infamous Stanley knife scene remains one of the most visceral and debated moments in British television history.

Alongside Oldman, Lesley Manville is quietly devastating as Sue. She represents the domestic sphere Bex’s violence constantly threatens to invade. Her growing unease and eventual confrontation with Bex provide the film’s moral anchor, highlighting the collateral damage of his choices. Manville conveys so much with just a look, a hesitant word – the fear, the frustration, the dawning realization of the monster her husband truly is. And Phil Davis as Yeti, the leader of a rival firm, offers a different kind of menace – older, perhaps wearier, but no less dangerous. Their encounters crackle with barely suppressed aggression.

### Echoes in the Stands

The Firm caused a significant stir upon its release, criticised by some for potentially glorifying the violence it depicted. Yet, Clarke’s detached, observational style refuses easy answers or moralizing. It simply presents the ugliness, the tribalism, the pathetic need for dominance, and asks: Why? What drives these men to seek validation through brutality? Is it purely about football, or something deeper rooted in masculinity, class, and a sense of powerlessness in other areas of life? These questions linger long after the brutal climax. The film’s stark portrayal, reportedly toned down slightly from Ashton's original script to appease BBC concerns about the violence, still felt incredibly potent. It didn’t shy away from the designer sportswear ('casuals') favoured by the hooligans, making the violence seem disturbingly contemporary and specific to that era. The film's budget was modest, typical for a TV production, but Clarke uses these limitations to his advantage, fostering a gritty realism that slicker productions often miss.

Its legacy is undeniable. While other films have tackled football violence, few match The Firm's raw power and psychological insight. It remains a benchmark, a challenging piece of television drama that refuses to look away. Nick Love’s 2009 remake, also titled The Firm, focused more heavily on the fashion and camaraderie, arguably missing the chilling core of Clarke’s original vision.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's sheer, uncompromising power, Alan Clarke's masterful direction, and Gary Oldman's unforgettable central performance. It's a near-perfect execution of its grim intentions, losing perhaps a single point only because its unrelenting bleakness makes it a difficult, though essential, watch.

The Firm isn't nostalgic comfort food; it's a potent shot of social realism that burns with intensity. It captured a specific, ugly aspect of late 80s British culture with unflinching honesty, leaving you shaken and contemplating the darkness that can reside behind the most ordinary of facades. A true standout from the era of vital television filmmaking.