What is it to truly live through time, not just mark its passing? Few films dare to ask this question with the visual audacity and intellectual grace of Sally Potter’s 1992 adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s novel, Orlando. Discovering this on a rented VHS tape, perhaps nestled between more conventional period dramas or the latest sci-fi thrillers, felt like stumbling upon a secret passage – a portal into a world both historically grand and intimately personal, rendered in strokes of breathtaking cinematic artistry. It wasn't just a movie; it felt like a moving tapestry, woven with threads of identity, gender, history, and the enduring human spirit.

A Tapestry Woven Across Centuries

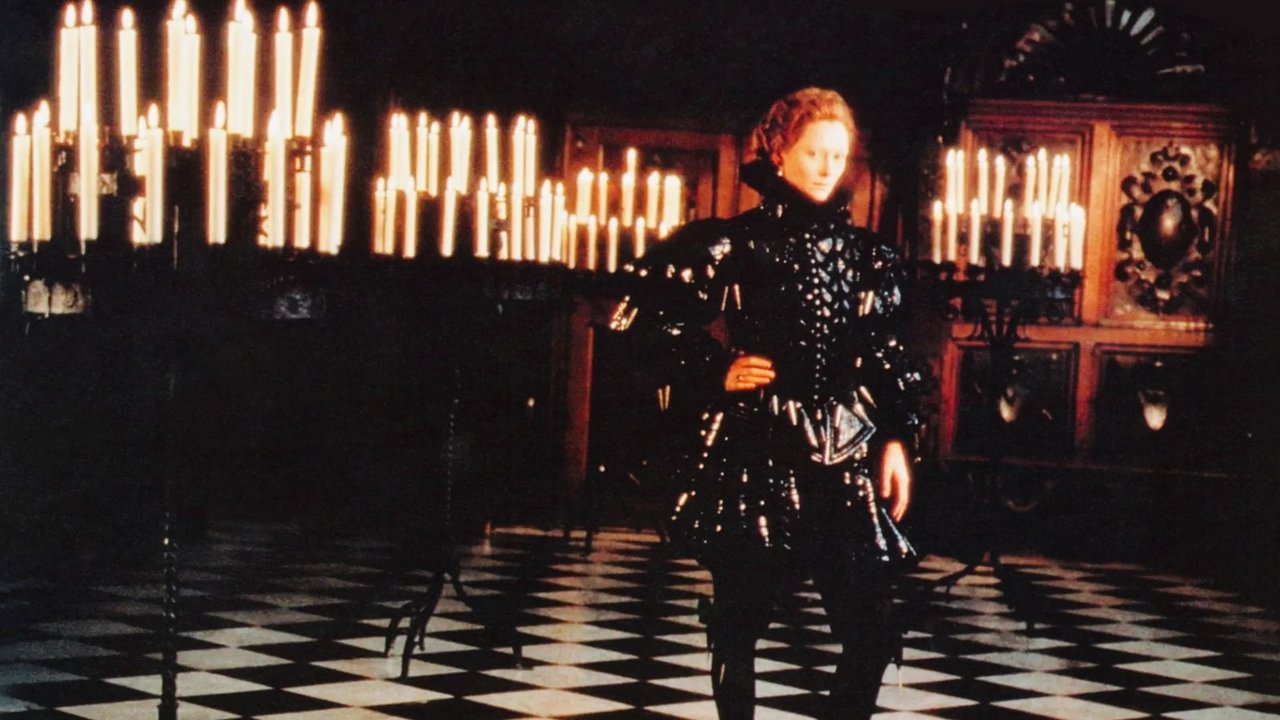

Adapting Woolf is no small feat. Her stream-of-consciousness style and thematic density demand more than mere transcription. Sally Potter, who both wrote the screenplay and directed, understood this implicitly. She doesn’t just translate the story of an English nobleman granted unnaturally long life and experiencing a mid-life change of sex; she interprets it, using the unique language of cinema to explore its core concerns. The film’s masterstroke lies in its episodic structure, dividing Orlando’s 400-year lifespan into distinct historical periods, each rendered with its own specific visual palette, texture, and mood by cinematographer Alexei Rodionov. From the crisp, formal light of the Elizabethan era to the shadowed intrigue of Constantinople, and the almost painterly quality of the 18th century, the visuals aren't just backdrop; they are participants in the narrative, reflecting Orlando's internal state and the shifting sands of time and culture.

The Incandescent Heart: Tilda Swinton

At the absolute center of this ambitious canvas is Tilda Swinton in a performance that remains utterly captivating. It’s less about impersonation across eras and more about embodying an essence – a watchful, curious, evolving soul navigating the constraints and freedoms offered by different centuries and, crucially, different genders. Swinton’s direct address to the camera, breaking the fourth wall, isn't a gimmick; it’s an invitation. It collapses the distance between viewer, character, and author, drawing us into Orlando's contemplative journey. Her stillness is as powerful as her moments of expressed emotion, conveying centuries of observation with a glance. It’s a performance of profound intelligence and ethereal presence, perfectly capturing the androgynous spirit Woolf envisioned. Interestingly, Swinton's connection to the role reportedly predates Sally Potter's involvement; the filmmaker Derek Jarman, a frequent collaborator with Swinton, had apparently envisioned her as Orlando years earlier, a testament to how perfectly suited she was for this unique challenge.

Artistry in Every Frame

Beyond Swinton, the film is a testament to collaborative artistry. The production design by Ben Van Os and Jan Roelfs, alongside Sandy Powell's meticulously crafted costumes, are characters in themselves. Each era feels distinct yet part of a cohesive whole. The Great Frost sequence, depicting the frozen Thames fair of 1607-08, is particularly iconic – a stunning blend of location shooting (reportedly involving elaborate sets built over frozen lakes in Russia) and visual effects that creates a dreamlike atmosphere, both beautiful and melancholic. It’s a sequence that showcases the film’s commitment to visual poetry over strict historical realism. And who could forget the inspired casting of the inimitable Quentin Crisp as Queen Elizabeth I? It’s more than stunt casting; it’s a resonant choice, bringing a figure known for challenging societal norms regarding gender and identity to embody the monarch who first grants Orlando favour, adding another layer to the film's exploration of performance and persona. Even Billy Zane as the elusive Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine brings a necessary spark of romantic adventure, albeit one filtered through Orlando's unique perspective.

Echoes Through Time: Themes and Reflections

Orlando delves into profound themes with a lightness of touch that prevents it from becoming overly academic. The fluidity of gender is presented not as a polemic, but as a lived experience, a shift in perspective that alters Orlando’s relationship with society, property, and power. What does it mean to be a man? What does it mean to be a woman? The film suggests these are roles shaped as much by historical context as by biology. It’s a perspective that feels remarkably resonant today, decades after its release. The film also ponders the nature of time itself – its relentless march, yet its subjective experience. Orlando doesn't simply age; they accumulate experience, observing the cyclical nature of human folly and desire. The recurring motif of the oak tree near Orlando’s ancestral home serves as a silent witness, a fixed point against which the tides of history and personal transformation ebb and flow.

Retro Fun Facts: Weaving the Magic

Bringing such an unconventional vision to the screen was, unsurprisingly, a journey in itself. Sally Potter reportedly spent seven years trying to secure funding for Orlando, a testament to her perseverance in championing a project that defied easy categorization – a hurdle many independent filmmakers faced then and now. The source material itself has a fascinating backstory: Woolf's novel was famously inspired by and dedicated to her lover, the aristocratic writer Vita Sackville-West, whose own life involved navigating societal expectations and gender complexities. Potter’s film subtly honours this lineage, infusing the narrative with an understanding of passionate creativity and unconventional love. The film’s budget, around $4 million (roughly $8.5 million today), was modest for its historical scope and visual ambition, making the richness achieved on screen all the more impressive – a victory for artistic vision over blockbuster bloat that resonated with arthouse audiences seeking something different in the early 90s cinematic landscape.

The Enduring Resonance

Orlando isn't a film that provides easy answers. It invites contemplation, leaving the viewer with lingering questions about identity, the passage of time, and the search for meaning across centuries. Its pacing is deliberate, its tone often meditative, demanding engagement rather than passive viewing. It might not have been the loudest film on the video store shelf, but its quiet power and visual splendour offered a unique and enriching experience.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Orlando earns a strong 8 for its sheer artistic bravery, its breathtaking visual execution, and Tilda Swinton's luminous, career-defining performance. Sally Potter's intelligent adaptation captures the spirit of Woolf while forging a distinct cinematic identity. The exploration of complex themes feels both timeless and remarkably prescient. While its meditative pace and arthouse sensibility might not connect with all viewers, and occasionally some historical periods feel slightly less developed than others, its profound beauty and intellectual depth make it a standout achievement of early 90s independent filmmaking.

Final Thought: More than just a period piece or a literary adaptation, Orlando remains a singular cinematic experience – a visually stunning, deeply thoughtful meditation on the fluidity of self that feels less like watching a story unfold and more like drifting through time itself.