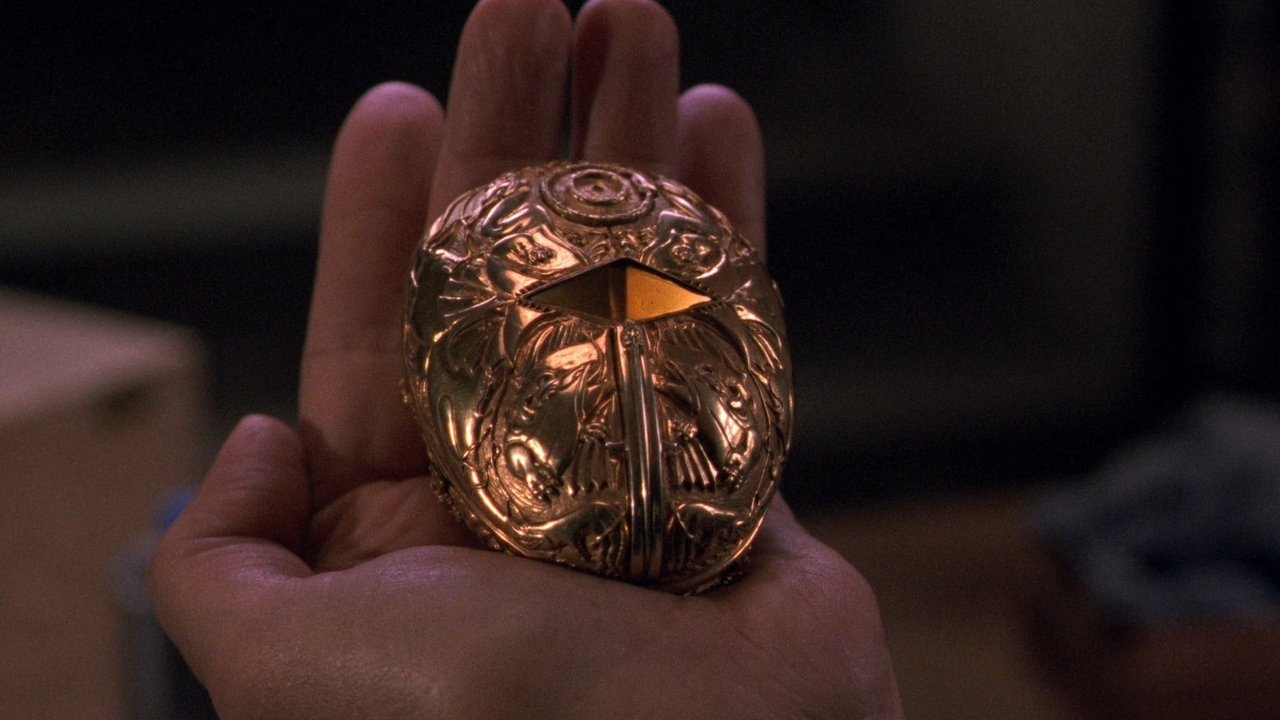

It begins not with fangs bared in the moonlight, or a shadowy figure lurking in a castle, but with something far more insidious: the ticking heart of a golden scarab. The Cronos device. Even now, recalling its intricate, almost beautiful clockwork mechanism sends a distinct shiver down the spine. Watching Guillermo del Toro's 1993 debut feature, Cronos, often felt like unearthing a forbidden artifact yourself, pulling a strangely heavy, unlabeled tape from the dusty back shelf of the video store, unsure of the secrets held within its magnetic ribbon.

This wasn't your typical early 90s horror fare. Forget the jump scares and the quipping killers. Cronos unfolds with the patient, measured dread of a decaying fairytale, steeped in Catholic iconography and the inescapable horror of the body's betrayal. It felt different, heavier, more... European, perhaps, even filtering through the CRT glow late at night.

### The Gilded Cage of Immortality

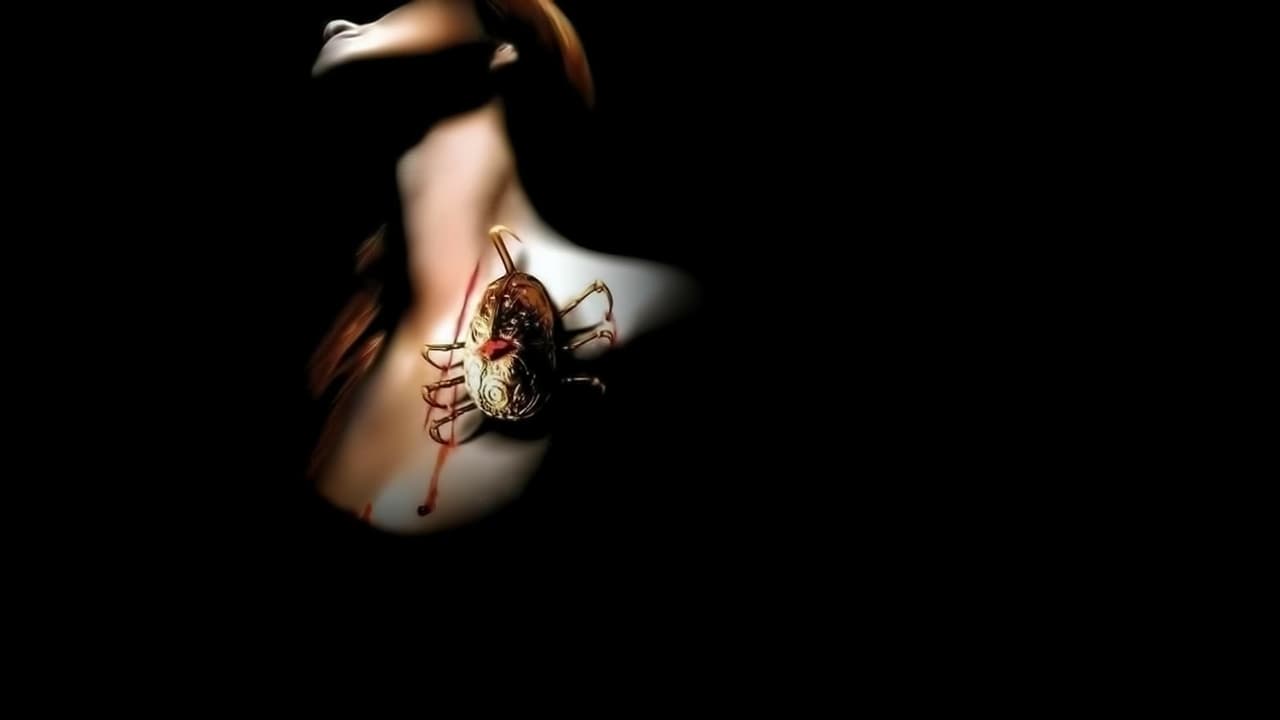

The premise is elegantly simple, yet rich with allegorical depth. Jesús Gris (Federico Luppi), a kindly, aging antique dealer, accidentally activates the Cronos device, hidden for centuries within the hollow base of an archangel statue. Created by a 16th-century alchemist fleeing the Inquisition, the device grants eternal life, but at a terrible cost. It latches onto Jesús, piercing his flesh with insect-like legs, injecting a substance that rejuvenates him but instills an unnatural, horrifying thirst – not just for blood, but for something more primal.

Luppi, a celebrated Argentinian actor, embodies Jesús's transformation with heartbreaking pathos. He doesn't become a suave predator overnight; he becomes ill, frail, his skin taking on a disturbingly waxy pallor, his humanity slowly, agonizingly draining away. It’s a performance of profound sadness, capturing the horror of addiction and unwanted transformation far more effectively than any snarling monster could. His relationship with his devoted, almost silent granddaughter, Aurora (Tamara Shanath), provides the film's aching emotional core – a beacon of innocence in a world succumbing to ancient darkness.

### Clockwork Horrors and Human Monsters

Opposing Jesús is the dying industrialist Dieter de la Guardia (Claudio Brook) and his brutish American nephew, Angel (Ron Perlman). De la Guardia, obsessed with obtaining the device, represents a different kind of decay – moral and spiritual. Brook portrays him with chillingly detached cruelty. And then there's Angel. Perlman, in the first of many collaborations with del Toro (a partnership reportedly initiated when the director, impressed by Beauty and the Beast, personally paid for Perlman's flight to Mexico when funds were tight), is terrifyingly effective. Hulking, oddly vain (obsessed with his nose job), and utterly devoid of empathy, Angel is pure, thuggish menace. He barely speaks Spanish, adding to his alienation, a blunt instrument of his uncle's avarice. Remember the sheer blunt force of his presence? He wasn't supernatural, just relentlessly cruel – perhaps the more disturbing monster.

Del Toro's visual signatures are already strikingly present. The fascination with insects, clockwork, and Catholic imagery; the interplay of beauty and horror; the focus on practical, visceral effects. The Cronos device itself is a masterpiece of design – ornate, beautiful, yet inherently sinister. The makeup effects charting Jesús's decline are subtle but deeply unsettling, evoking pity as much as revulsion. This wasn't CGI gloss; this was tactile, physical decay you felt in your gut, the kind of effect that stuck with you long after the tape ejected. The film was made for a relatively modest $2 million, but del Toro squeezed every peso for maximum atmospheric impact, filming predominantly in Mexico City, grounding the fantastical elements in a tangible reality.

### A Different Kind of Vampire Tale

Cronos isn't just a horror film; it's a deeply melancholic meditation on time, mortality, faith, and family. It reinvents vampire lore not through capes and castles, but through the lens of addiction, disease, and the desperate human craving for more time, regardless of the cost. It’s a film filled with haunting images: Jesús sleeping in a toy chest like a child, lapping spilled blood from a pristine white bathroom floor, the final, heartbreaking choice he must make.

There's a quiet power to Cronos that distinguishes it. It doesn't rely on speed or spectacle, but on mood, character, and the slow tightening of a horrifying predicament. It was a startlingly mature debut, announcing the arrival of a unique visionary voice in genre cinema. Its success at festivals like Cannes Critics' Week rightfully put Guillermo del Toro on the international map, paving the way for later works like The Devil's Backbone and Pan's Labyrinth, which share its DNA of dark fantasy and historical tragedy. Doesn't that meticulous, almost obsessive attention to detail still feel uniquely his?

Rating: 9/10

Cronos is a masterpiece of mood and melancholy horror. Its deliberate pace and focus on character over cheap thrills might not satisfy every gorehound, but its stunning visuals, heartbreaking performances (especially Luppi's), and unique take on vampirism are unforgettable. The practical effects feel tangible, the atmosphere is thick with dread, and the underlying themes resonate deeply. It earns its high rating through sheer artistry, emotional depth, and the establishment of del Toro's singular vision. It's a film that proves horror can be beautiful, tragic, and profoundly human, a haunting reminder of the price of eternity, perfectly preserved on those cherished magnetic tapes.