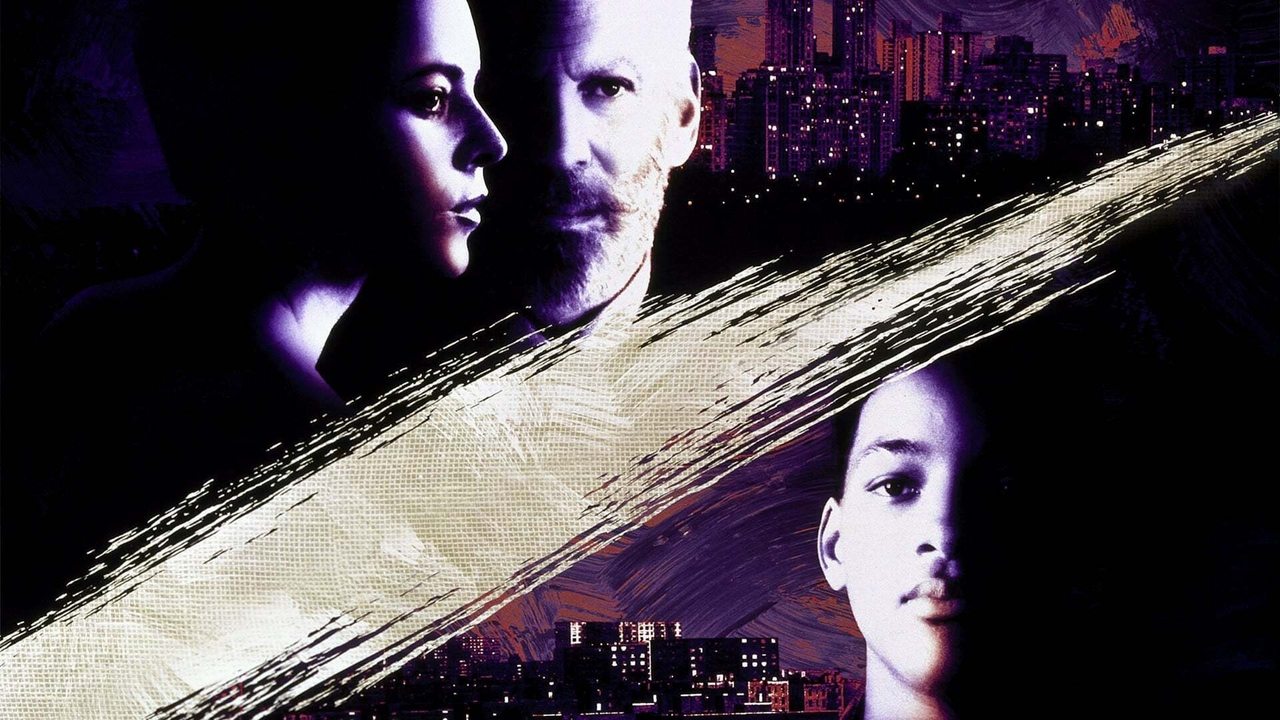

It starts with a story, doesn't it? A captivating tale spun late at night in a luxurious Fifth Avenue apartment, candlelight flickering across anxious, wealthy faces. That's the entry point into Fred Schepisi's sharp, unsettling 1993 adaptation of John Guare's celebrated play, Six Degrees of Separation. This isn't your typical cozy VHS night fare; it leaves you with a prickle under the skin, a discomforting awareness of the porous boundaries between truth and performance, connection and exploitation. Seeing it again, decades after first sliding that tape into the VCR, its observations feel perhaps even more pointed now.

### The Ultimate Imposter

The premise is deceptively simple, yet endlessly complex. Flanagan "Flan" Kittredge (Donald Sutherland) and Louisa "Ouisa" Kittredge (Stockard Channing, reprising her iconic stage role) are sophisticated New York art dealers, navigating a world built on appearances and transactions. Their carefully constructed evening is disrupted by the arrival of Paul (Will Smith), a young, charismatic Black man bleeding from a supposed mugging. He claims to be the son of Sidney Poitier and a Harvard classmate of their children, weaving an intoxicating narrative filled with intellectual references, charm, and vulnerability. The Kittredges, and soon their friends, are utterly captivated. But who is Paul, really? Is he a charming rogue, a dangerous sociopath, or something far more complicated – a mirror reflecting the emptiness and desires of those he encounters?

### A Star-Making Turn, A Masterclass Preserved

Let's talk performances, because they are the magnetic core of this film. Stockard Channing is simply extraordinary. Having originated Ouisa on stage, she embodies the character with a depth that feels lived-in and utterly authentic. Her journey from charmed hostess to profoundly disturbed participant is mesmerizing. Watch her face as Paul holds court – the initial fascination, the dawning maternal warmth, later replaced by confusion, betrayal, and a searching empathy that transcends judgment. It's a performance layered with intelligence and vulnerability, rightfully earning her an Oscar nomination. Sutherland, as Flan, is pitch-perfect as the more cynical, business-minded half, initially intrigued but quicker to anger when the illusion shatters.

And then there's Will Smith. This was a pivotal moment. Many knew him only as the charismatic rapper or the goofy star of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Taking on Paul was a gamble, a deliberate step into serious dramatic territory. And he pulls it off with astonishing confidence. Smith captures Paul’s chameleon-like quality – the effortless mimicry, the seductive intelligence, the flashes of desperation beneath the polished veneer. It’s a star-making dramatic turn, proving his range far beyond comedy. The story goes that Smith, eager for the role, essentially immersed himself in the world the character aspired to, spending time with affluent families to understand that milieu. It paid off, lending a fascinating authenticity to his portrayal of an outsider mastering the language of the elite. Supporting players like Ian McKellen and Mary Beth Hurt also shine as members of the Kittredges' circle caught in Paul's orbit.

### From Confines to Canvas

Adapting a play famed for its rapid-fire dialogue and contained setting presents challenges. Director Fred Schepisi (Roxanne, A Cry in the Dark) and writer John Guare (adapting his own work) deftly navigate this. While retaining the crackling intelligence of the script, Schepisi opens up the action, utilizing flashbacks and elegant New York City locations – Central Park, museums, those opulent apartments – to give the story cinematic scope without losing its intense focus. The frantic energy of the Kittredges recounting the initial encounter, overlapping dialogue tumbling out as they piece together the story for the audience (and themselves), feels both theatrical and intensely cinematic. There’s a visual richness here, particularly the recurring motif of the double-sided Kandinsky painting – one side abstract, the other figurative – mirroring the film's themes of duality and perception.

### Echoes of Truth (and Consequences)

One of the most fascinating aspects, especially looking back, is the film's basis in reality. Guare was inspired by the true story of David Hampton, a young con artist who similarly infiltrated the homes of several prominent New Yorkers in the early 80s by claiming connections to famous figures. This grounding in fact adds another layer of unease. How easily can we be swayed by a convincing performance? What does our willingness to believe say about our own needs and prejudices?

The film wasn't a massive box office smash ($15 million budget, around $6.4 million US gross), but its critical reception, especially Channing's acclaim, cemented its place as a significant piece of 90s cinema. It’s a film that dissects class, race, identity, and the yearning for genuine connection in a world increasingly mediated by surfaces. Paul isn't just lying; he's offering his listeners a fantasy they desperately want to believe – that they are sophisticated, compassionate, and connected to something larger than themselves. His crime, perhaps, is less the deception itself and more the exposure of their own vulnerabilities and hypocrisies. Doesn't that core question – how much of our identity is curated for others – feel incredibly relevant in today's social media age?

The title itself, referencing the theory that everyone on the planet is connected by six intermediaries, becomes profoundly ironic. These characters inhabit a world of immense privilege and access, yet genuine human connection seems agonizingly out of reach. Paul, the ultimate outsider, paradoxically becomes the catalyst forcing them to confront their own isolation.

***

Rating: 9/10

Six Degrees of Separation is a brilliantly acted, intelligently written, and deeply unsettling film that has only gained resonance over time. Channing's performance is a masterclass, Smith's dramatic arrival is undeniable, and Guare's script remains a razor-sharp exploration of social strata and the stories we tell ourselves. It justifies its high rating through its powerhouse acting, its successful stage-to-screen translation, its enduring thematic depth, and its lingering power to provoke thought long after the credits roll. It’s a sophisticated, sometimes uncomfortable watch that reminds us how readily we accept illusions, especially when they flatter us.

What lingers most is Ouisa's final, haunting realization – the experience, however fraudulent, has irrevocably changed her, leaving her adrift in a world she thought she knew. It's a feeling that stays with you, a testament to a film that dared to dissect the glittering surfaces of society and find something far more complex and troubling underneath. A truly unforgettable piece of 90s cinema well worth revisiting on whatever format you can find.