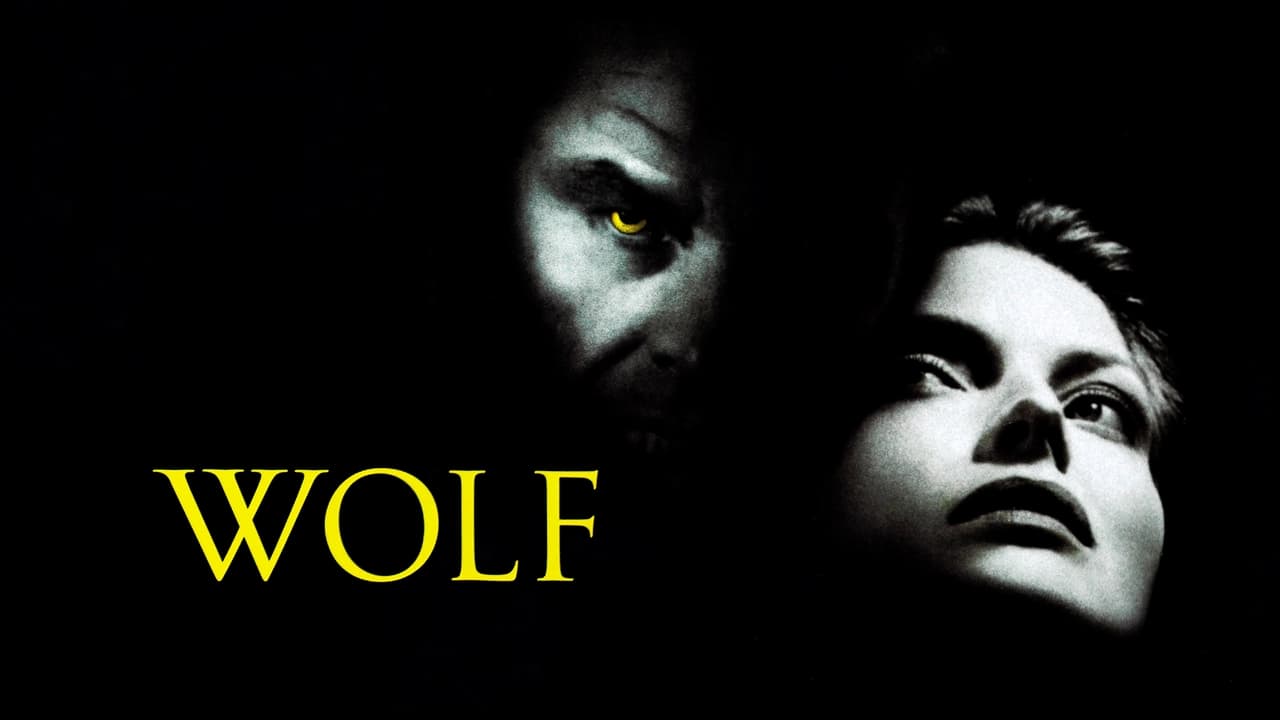

Okay, let's dim the lights, maybe pour something contemplative, and settle in. Remember pulling Wolf (1994) off the shelf at Blockbuster? The cover alone – Jack Nicholson's intense gaze hinting at something primal beneath the surface – promised a different kind of creature feature. And different it was. It wasn't the gore-soaked transformation scenes many werewolf films leaned into back then. Instead, director Mike Nichols, a filmmaker we usually associate with sharp character dramas like The Graduate (1967) or Working Girl (1988), gave us something more akin to a brooding, elegant thriller draped in gothic romance, asking questions about aging, power, and the animal lurking within civilized society.

A Bite of Midlife Crisis

The setup is deceptively simple, almost mundane. Will Randall (Jack Nicholson) is a respected, albeit aging and somewhat weary, book editor-in-chief facing obsolescence. He’s being pushed out by a younger, ruthlessly ambitious protégé, Stewart Swinton (a perfectly viperous James Spader), backed by publishing tycoon Raymond Alden (Christopher Plummer). Driving home one snowy Vermont night, Randall hits a wolf. When he gets out to check, the creature bites him before vanishing into the woods. This isn't just an inciting incident; it's the catalyst for a profound, unsettling change. The bite doesn't just heal; it revitalizes him. His senses sharpen, his energy returns, his graying hair darkens. He becomes more assertive, more decisive... more predatory. It’s a fascinating metaphor – is this lycanthropy, or merely a midlife crisis manifesting in a feral, almost supernatural way?

Nicholson Unleashed, Subtly

Watching Nicholson navigate this transformation is the film's dark, beating heart. He’d reportedly harboured an ambition to play a werewolf for years, and you can feel that investment. It's not the scenery-chewing Jack of The Shining (1980), but something far more internal and nuanced, at least initially. He masterfully conveys Randall’s confusion, fear, and burgeoning exhilaration. There’s a quiet intensity in his rediscovered confidence, a dangerous glint in his eye as he starts turning the tables in the cutthroat publishing world. We see the gradual shifts – the heightened senses leading to almost comical moments (overhearing whispers across a crowded room) but also to a terrifying loss of control. It’s a performance that grounds the fantastical premise in psychological reality. What does it feel like to have your senses overloaded, your instincts sharpened to a razor's edge after decades of intellectual detachment?

Shadows and Intrigue

The film excels in atmosphere. Nichols, alongside legendary cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno, crafts a world of sleek corporate offices, shadowy Manhattan apartments, and sprawling, isolated estates bathed in moonlight. It feels expensive, sophisticated, yet constantly shadowed by something ancient and untamed. The score by the maestro Ennio Morricone adds layers of melancholic beauty and suspense, avoiding typical horror cues for something more evocative and mournful. This isn't a jump-scare fest; it's a mood piece, a slow burn that relies on suggestion and the internal struggles of its characters.

Into this world steps Laura Alden (Michelle Pfeiffer), the tycoon's cynical, disillusioned daughter. Pfeiffer brings a captivating blend of vulnerability and weary strength to the role. Her connection with Randall feels less like a traditional romance and more like two wounded souls recognizing a shared wildness, a mutual dissatisfaction with the polite cages they inhabit. Their scenes together have a charged, almost dangerous intimacy. Can trust exist when one partner might literally devour the other? It's a dynamic that adds another layer to the film's exploration of human (and inhuman) connection. She wasn't the first choice – apparently, Sharon Stone was considered – but Pfeiffer's specific brand of cool intelligence feels absolutely right here.

The Devil You Know

And then there's James Spader. His Stewart Swinton is a magnificent creation of slicked-back hair, smug confidence, and utterly believable corporate treachery. He represents the other kind of predator – the boardroom shark, ruthless and territorial in his own way. The rivalry between Randall and Swinton becomes a fascinating study in contrasts: the civilized man grappling with literal animal instincts versus the seemingly refined man driven by purely savage ambition. Spader reportedly relished the role, and his performance is a masterclass in conveying menace beneath a polished veneer. Their confrontations crackle with tension, blurring the lines between human and beast in the corporate jungle.

More Metaphor Than Monster

Let's talk about the wolf itself. The effects, supervised by the legendary Rick Baker (who famously handled An American Werewolf in London), are deliberately restrained for much of the film. Baker aimed for subtle, suggestive transformations – changes in eye colour, slight shifts in facial structure, enhanced physicality – rather than full-blown monster makeup until the climax. This decision, while perhaps disappointing gorehounds back in '94, serves the film's thematic core. Wolf is less interested in the mechanics of lycanthropy than in what it represents. It’s about reclaiming vitality, the danger of unchecked power, and the thin line between instinct and savagery. The production itself wasn't entirely smooth sailing; the script, originally penned by novelist Jim Harrison, went through significant rewrites by Wesley Strick to shape it into the thriller Nichols envisioned. Some say Harrison's more mystical, internal focus was diluted, but the resulting blend still offers plenty to chew on. Despite a hefty $70 million budget (around $145 million today), its $131 million worldwide gross ($272 million today) made it profitable, though perhaps not the blockbuster some anticipated given the star power.

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Why a 7? Wolf is a fascinating, beautifully crafted film anchored by stellar performances, particularly from Nicholson and Spader. Its moody atmosphere, intelligent themes, and unique blend of corporate thriller and gothic horror make it stand out. Nichols' direction lends it an elegance rare in the genre. However, it sometimes feels caught between its intellectual ambitions and genre demands. The third act leans more heavily into conventional werewolf tropes, slightly undercutting the nuanced buildup. The central romance, while compellingly acted, occasionally feels secondary to the power struggles. Yet, these points don't break the spell entirely. The film works because it takes its unusual premise seriously, exploring the unsettling allure of unleashing the beast within the confines of modern life. It’s a film that lingers, less for its scares and more for the questions it poses about our own civilized masks.

Pulling this tape out now evokes a specific kind of rainy-night feeling – a sophisticated chill rather than a raw fright. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most compelling monsters aren't the ones with fur and fangs, but the ones wrestling with the complexities of their own nature, hidden just beneath the surface. What part of ourselves do we suppress in the name of fitting in, and what happens when it finally breaks free?