Okay, fellow travelers down the aisles of memory lane, let's blow the dust off a real gem from the mid-90s independent boom. Remember that section in the video store, tucked away past the New Releases, usually labeled "Indie" or "Art House"? That's where you might have stumbled upon Tom DiCillo's hilariously, painfully authentic Living in Oblivion (1995). This wasn't your typical explosive blockbuster vying for shelf space; instead, it offered something far more fascinating for anyone curious about how the cinematic sausage gets made – especially when the grinder keeps jamming.

Forget meticulously planned CGI spectacles for a moment. Living in Oblivion throws us headfirst into the glorious, caffeine-fueled chaos of micro-budget filmmaking, where Murphy's Law isn't just a suggestion, it's the damn shooting script. This film doesn't just show you the trials of moviemaking; it feels like them.

Welcome to the Set from Hell

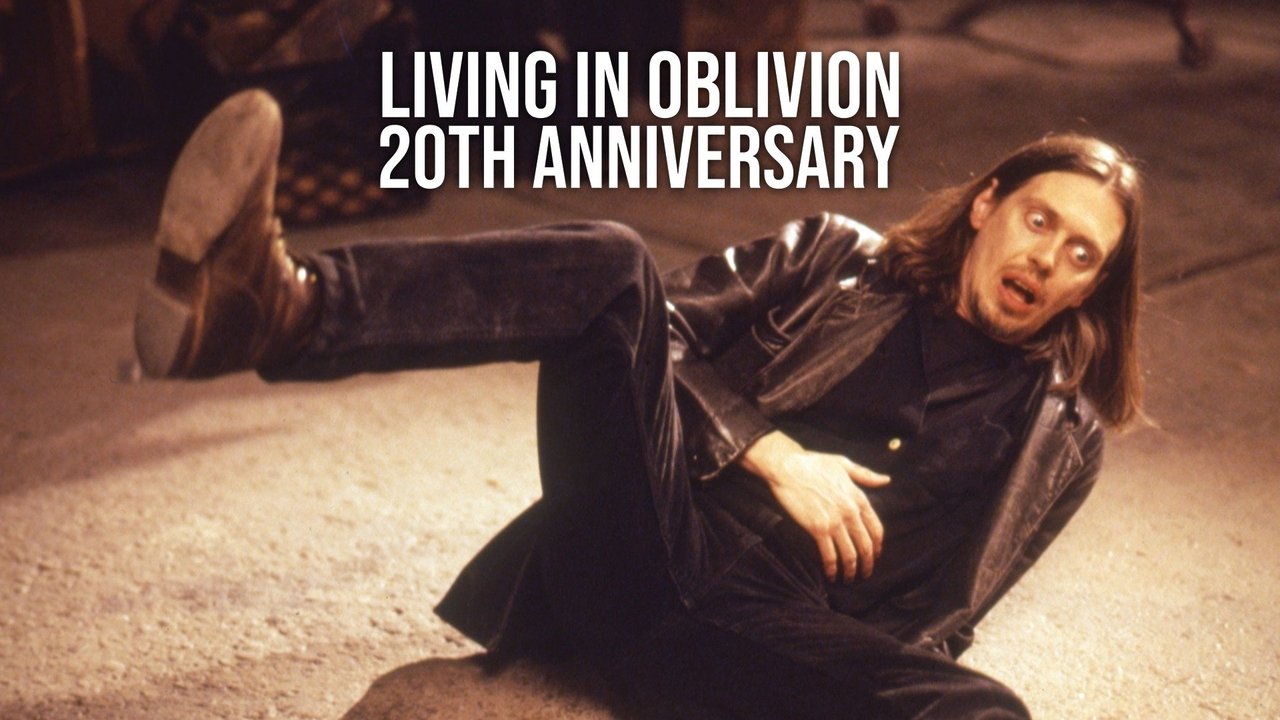

The premise is simple yet brilliant: we witness the increasingly disastrous attempts to film a low-budget independent movie, primarily through the fraying nerves of its director, Nick Reve, played with masterful exasperation by the legendary Steve Buscemi. If you've ever worked on any creative project with limited resources and maximum ego, Nick's plight will feel startlingly familiar. The film unfolds in three distinct segments, playing cleverly with reality, dreams, and the differing perspectives of the crew, shifting between gritty black-and-white and hopeful color stock. This structural choice isn't just stylistic flair; it mirrors the fractured, often surreal experience of being trapped on a set where nothing goes right.

Remember Buscemi from Reservoir Dogs (1992) or his later Coen Brothers collaborations? Here, he channels that signature intensity into pure creative frustration. His epic meltdown over a scene ruined again is the stuff of indie legend – raw, uncomfortable, and hysterically relatable. It's a scene fueled, apparently, by director DiCillo's own nightmarish experiences trying to wrangle a young Brad Pitt on his previous film, Johnny Suede (1991). Retro Fun Fact: DiCillo actually wrote the part of Nick specifically for Buscemi, perfectly capturing that blend of artistic passion and barely suppressed rage.

A Cast Firing on All (Sputtering) Cylinders

Alongside Buscemi, the ensemble cast is simply perfect. Catherine Keener shines as Nicole Springer, the lead actress enduring not only the technical mishaps but also the wandering hands and inflated self-importance of her co-star, Chad Palomino. Keener brings a weary resilience to Nicole; you see the flicker of hope battling the encroaching despair in her eyes. It’s a role that truly showcased her talent early on. Chad, played with preening perfection by Dermot Mulroney, is the epitome of the handsome-but-vacant actor convinced of his own genius. His clueless pronouncements and passive-aggressive suggestions ("Maybe my character wouldn't look?") are comedic gold, nailing a type instantly recognizable to anyone who's spent time near a film set.

And who could forget the memorable film debut of Peter Dinklage as Tito, an actor hired for a dream sequence who is utterly fed up with the condescending clichés thrust upon dwarf actors? His sharp refusal to play the stereotype is both funny and pointed, a standout moment delivered with characteristic gravitas. Retro Fun Fact: The entire first segment of the film was initially shot as a short film using funds DiCillo raised himself, partly through donations, after struggling to finance a feature based on his frustrating Johnny Suede experience. Its success paved the way for the rest of the movie.

The Craft of Capturing Chaos

Tom DiCillo, who also wrote the screenplay (winning the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award at Sundance for his efforts), directs with a keen eye for the absurdities of the process. The perpetually malfunctioning smoke machine, the out-of-focus shots, the sound guy picking up ambient noise, the boom mic dipping into frame – these aren't just gags; they're battle scars from the indie filmmaking trenches. There's an affection here, even amidst the satire. DiCillo understands the passion that drives people to endure such madness for the sake of creation. The shift between the grainy 16mm black-and-white (representing Nick's initial dream sequence and later, Nicole's perspective) and the warmer 35mm color film used for the "real" set segments visually underscores the different layers of perception and aspiration.

This isn't a film about practical effects in the traditional action movie sense, but about the practical realities of making anything appear seamless on screen when you have no money and everything is conspiring against you. Remember how even simple things could look challenging on older film stock or under poor lighting on your CRT TV back in the day? This film embraces that lack of polish as part of its aesthetic and narrative. It found its audience not necessarily in wide release multiplexes, but through critical praise and word-of-mouth, becoming a beloved cult classic, especially cherished by film students and aspiring directors who saw their own struggles reflected on screen.

Rating: 9/10

Why such a high score for a film about failure? Because Living in Oblivion succeeds brilliantly as a film about the chaotic, frustrating, yet strangely addictive process of making one. The performances are pitch-perfect, the writing is razor-sharp and painfully funny, and its structure is inventive. It captures the specific anxieties and absurdities of 90s independent filmmaking with uncanny accuracy and enduring charm. It’s more than just a comedy; it’s a love letter, albeit a slightly exasperated one, to the messy art of cinema itself.

For anyone who ever dreamed of making movies, or just loves watching the wheels come off in spectacular fashion, Living in Oblivion remains a vital, hilarious slice of indie history – a reminder that sometimes the most compelling drama happens behind the camera.