Okay, pull up a chair, maybe pour yourself something thoughtful. We're not digging into the usual action-packed rental aisle staple today. Instead, we're venturing into territory that might have occupied a quieter, perhaps dustier, corner of the video store – the kind of film that didn't scream for attention with explosions on the cover, but promised something deeper, something that might stick with you long after the VCR clicked off. I'm talking about Abbas Kiarostami's haunting and profound 1997 Palme d'Or winner, Taste of Cherry (Ta'm e Guilass).

Remember encountering films like this back then? Maybe not on a casual Friday night pizza-and-movie run, but perhaps through a recommendation, or stumbling upon it in the 'World Cinema' section, a stark contrast to the usual Hollywood fare. Taste of Cherry is precisely that kind of discovery – a film that doesn't offer easy answers, but instead poses a quiet, insistent question about the very value of existence.

A Drive Towards Oblivion?

The premise is deceptively simple, yet loaded with existential weight. We follow Mr. Badii, a middle-aged man played with unnerving stillness by Homayoun Ershadi, as he drives his Range Rover through the barren, dusty hills surrounding Tehran. He’s searching for someone, anyone, willing to perform a specific task for a large sum of money: to come to a pre-dug grave on a remote hillside the following morning and either help him if he’s somehow changed his mind and is still alive, or cover his body with earth if he has succeeded in taking his own life.

It's a stark, uncomfortable setup. Badii’s interactions with the potential candidates he picks up – a young, hesitant Kurdish soldier, a wary Afghan seminarian studying religious law, and finally, an older, wiser Azeri taxidermist – form the core of the film. Each conversation unfolds largely within the confines of the car, Kiarostami often employing his signature technique of filming each actor separately, sometimes having them deliver lines directly to him positioned near the camera. This method, born partly of necessity and partly of artistic choice, creates a subtle but powerful sense of isolation between the characters, even as they share the intimate space of the vehicle. It forces us, the viewers, to bridge the gap, to focus intently on the words, the expressions, the silences.

The Weight of Stillness

Homayoun Ershadi’s performance is central to the film's power. Discovered, incredibly, by Kiarostami himself while literally stuck in Tehran traffic, Ershadi brings a quiet desperation and profound weariness to Mr. Badii. His face is often impassive, his voice calm, yet beneath the surface, we feel the immense burden he carries. He doesn't reveal why he wants to end his life – a deliberate choice by Kiarostami that shifts the focus from the specific cause of despair to the universal question of choosing life or death. Is his quest selfish? Is it a right? The film refuses to judge, merely presenting the situation with a quiet intensity.

The non-professional actors Badii encounters bring their own unique textures. The soldier's fear, the seminarian's theological objections ("Suicide is a major sin!"), and crucially, the taxidermist's grounded perspective, offer different facets of human response to Badii's request. It's the taxidermist, Mr. Bagheri (Abdolrahman Bagheri), who provides the film's titular anecdote – a story about how the simple taste of mulberries once pulled him back from the brink of suicide. "You want to give up the taste of cherries?" he gently prods Badii, suggesting that the sensory experiences, the small beauties of the world, are reasons enough to endure.

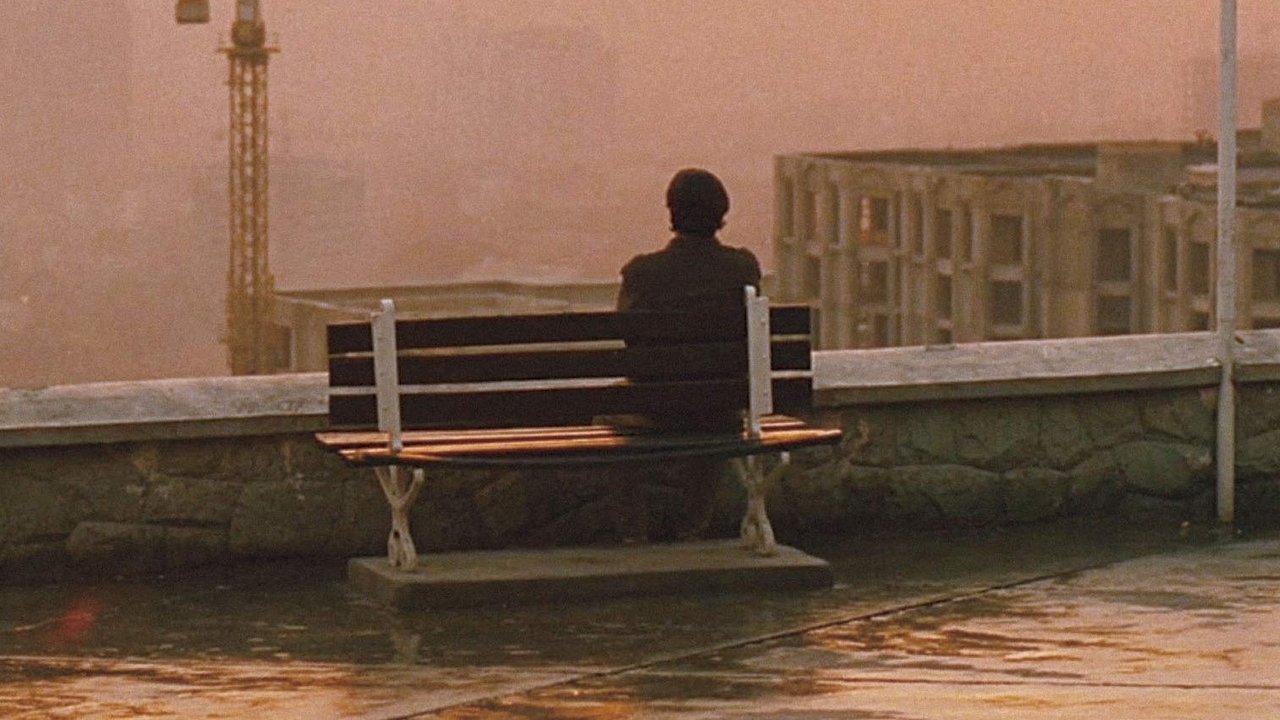

Landscape as Soulscape

Kiarostami, a master of cinematic minimalism, uses the landscape itself as a character. The dusty, construction-scarred hills outside Tehran aren't just a backdrop; they reflect Badii's internal state – arid, desolate, perhaps on the verge of transformation or collapse. The long takes, the patient rhythm of the driving, the ambient sounds of wind and distant machinery – all contribute to a meditative, almost trance-like atmosphere. This isn't a film that rushes; it asks you to slow down, to observe, to contemplate alongside its protagonist.

Interestingly, despite its heavy themes and minimalist approach, Taste of Cherry faced hurdles. It was initially banned in Iran, only allowed to screen after its prestigious Palme d'Or win at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival (an award it famously shared with Shohei Imamura's The Eel). Even its ending proved controversial – a sudden shift to camcorder footage showing Kiarostami and the crew filming, breaking the fourth wall entirely. Some found it jarring, others a profound reminder of the artifice of cinema and, perhaps, a subtle affirmation of life continuing beyond the narrative frame.

A Lingering Aftertaste

So, is Taste of Cherry a typical "VHS Heaven" comfort watch? Absolutely not. It’s challenging, philosophical, and demands patience. It doesn't offer catharsis in the conventional sense. But revisiting it, or perhaps discovering it for the first time, is a deeply rewarding experience. It reminds us of a time when world cinema gems could occasionally pierce the mainstream consciousness, offering radically different perspectives and cinematic languages. It pushes us to consider life's fundamental questions without providing easy answers. The film doesn't tell you what to think, but it absolutely makes you feel and ponder.

Rating: 9/10

This near-masterpiece earns its high score through its profound thematic depth, Homayoun Ershadi's unforgettable central performance, and Abbas Kiarostami's masterful, minimalist direction. It’s a demanding film, and its deliberate pace and ambiguous ending might not resonate with everyone, preventing a perfect score for general accessibility. However, its power lies in its quiet insistence on confronting life's biggest questions, using the simplest of cinematic tools to achieve extraordinary emotional and intellectual resonance.

It’s a film that stays with you, not unlike the memory of a specific taste – lingering, complex, and prompting reflection long after the screen goes dark. What, indeed, is the taste of your own cherries?