### Patience, Poetry, and the Unseen Horizon

There's a particular kind of quietude that settles over you when watching Abbas Kiarostami's The Wind Will Carry Us (1999). It’s not the silence of emptiness, but the resonant quiet of waiting, of observing, of life unfolding at its own unhurried pace. Landing near the very end of our beloved VHS era, this wasn't the kind of tape you grabbed for a Friday night pizza party. No, this was more likely nestled in the 'World Cinema' or 'Art House' section of the more discerning video stores – a plain cover hinting at something profound, something different. And different it certainly was. Discovering a film like this back then felt like uncovering a secret, a cinematic language far removed from Hollywood’s roar.

An Outsider's Gaze

The premise, like much of Kiarostami's work, is deceptively simple. A small crew, led by a man referred to only as "the Engineer" (Behzad Dorani), arrives in a remote Kurdish village in Iran. Their purpose is deliberately obscured, hinted at involving a traditional mourning ritual connected to a very elderly, unseen woman who is near death. Dorani, our surrogate, spends his days waiting, driving up a nearby hill to catch fleeting mobile phone reception, interacting tentatively with the villagers – children, farmers, a young woman milking a cow in a darkened barn. We, like the villagers, are kept somewhat at arm's length from the crew's true intentions, forced instead to simply be in this place, to watch and listen.

The Kiarostami Touch

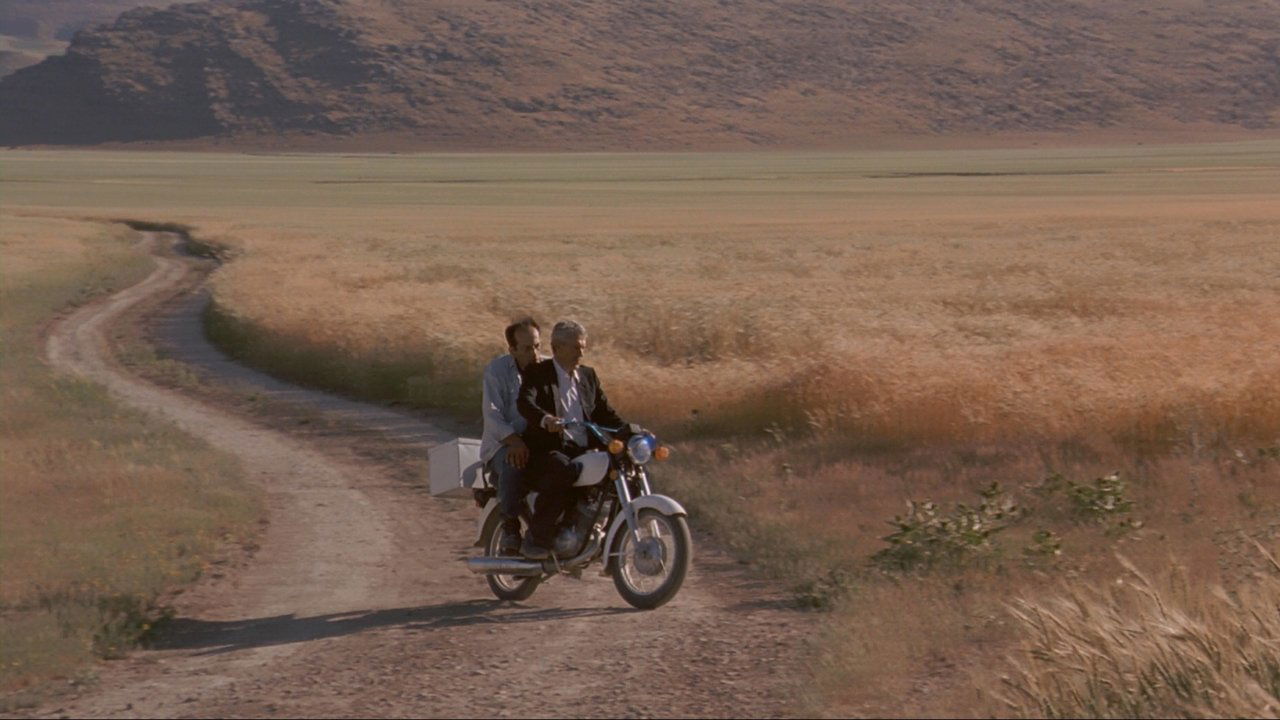

If you knew Kiarostami's name back then, perhaps from the Palme d'Or winning Taste of Cherry (1997) or the brilliant Close-Up (1990), you'd anticipate his signature style. The Wind Will Carry Us delivers it beautifully. Long, meditative takes allow the stunning, sun-baked landscapes to breathe, becoming characters in themselves. Much of the crucial action, including conversations on the phone and the fate of the old woman, happens off-screen, forcing us to engage our imagination, to piece together the narrative through fragments and inference. This isn't lazy filmmaking; it's a deliberate choice, trusting the audience to connect the dots and find meaning in the spaces Kiarostami leaves open. He masterfully uses sound – the wind, the distant calls, the sputter of the Engineer's car – to paint a world richer than what we strictly see.

Life in the Waiting Room

What truly resonates is the film's profound meditation on life, death, and the rhythms connecting them. While the Engineer waits for death to occur (for reasons never fully confirmed, but likely journalistic or anthropological), life bursts forth all around him. Children play, workers toil, conversations meander through philosophy and everyday concerns. There’s a recurring motif of digging – a ditch digger, communications trenches, eventually a grave – suggesting layers of meaning beneath the surface. The film subtly contrasts the urbanite Engineer's detached, technologically-tethered impatience with the village's organic, cyclical existence. Doesn't this tension between 'modern' schedules and the timeless pulse of nature still feel incredibly relevant today?

Authenticity and Hidden Poetry

Behzad Dorani, one of the few professional actors, carries the film with a wonderfully nuanced performance. He embodies the educated outsider – slightly awkward, sometimes impatient, yet capable of connection and quiet reflection. The real magic, however, lies in Kiarostami's work with the local villagers, many of whom were non-actors playing versions of themselves. Their interactions feel unscripted, genuine, lending the film an almost documentary-like authenticity. It’s a testament to Kiarostami’s unique ability to blur the lines between fiction and reality, capturing moments of unguarded truth.

Interestingly, the film's title comes from a poem by the celebrated Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad, whose work is recited within the film. This poetic sensibility permeates the entire runtime. Kiarostami wasn’t just documenting; he was composing a visual poem about existence itself. Filming in such a remote location reportedly presented its own challenges, yet the result feels effortless, lived-in. The film’s patience and artistry were recognized, notably winning the Grand Special Jury Prize and the FIPRESCI Prize at the Venice Film Festival that year – a significant nod to its unique power.

The Lingering Echo

The Wind Will Carry Us is not a film that provides easy answers or conventional narrative satisfaction. Its pace is deliberate, demanding patience and attention. It asks us to slow down, to observe the world differently, to find beauty and meaning not just in grand events, but in the texture of everyday life, in the connections forged and missed, in the landscapes that hold silent witness to it all. Picking up that VHS tape might have felt like a gamble back in the day, a deviation from the norm. But for those who took the chance, the reward was a film that lingered long after the credits rolled, its gentle rhythms and profound questions echoing in the quiet.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: This near-masterpiece earns its high score through Kiarostami's singular artistic vision, its profound thematic depth, stunning cinematography, and the authentic portrayal of life it captures. Its deliberate pace and ambiguity are not flaws but integral parts of its unique power, demanding engagement from the viewer. While perhaps not for everyone seeking fast-paced entertainment, its poetic beauty and philosophical resonance are undeniable.

Final Thought: It leaves you pondering the things we wait for, the life that happens while we're waiting, and the quiet poetry hidden in the folds of the everyday world.