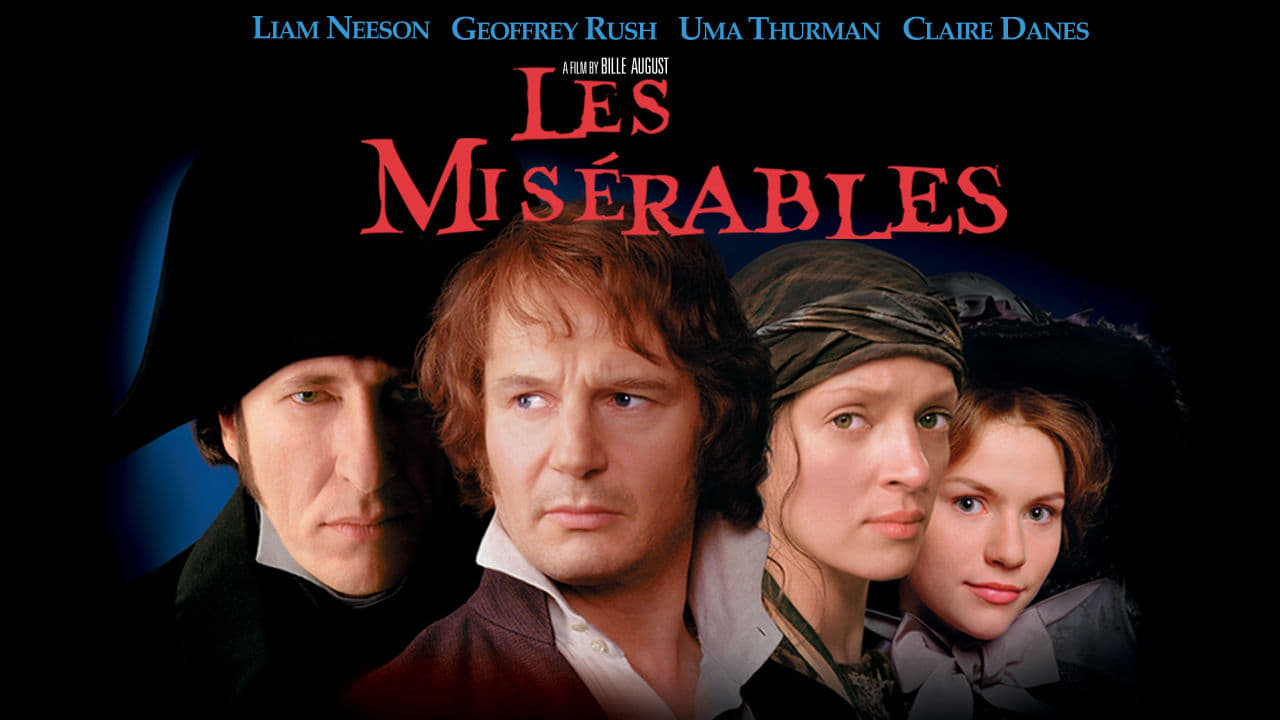

Okay, fellow tape travelers, let's rewind to a time when adapting a literary giant felt like a monumental task, especially when stepping out of the shadow of a certain, globally dominant musical. I’m talking about Bille August's 1998 take on Victor Hugo's Les Misérables. Pull up a comfy chair, maybe grab a slightly dusty beverage, because this isn't the sing-along version – and perhaps that's exactly where its quiet power lies.

What strikes you first, settling into this film years later, is the sheer weight it carries, embodied so profoundly by Liam Neeson as Jean Valjean. Fresh off the seismic impact of Schindler's List (1993), Neeson brings not just star power but a palpable sense of inner turmoil and weary resilience. His Valjean is less a soaring tenor, more a burdened soul etched with the harsh lines of injustice. This adaptation hinges on the raw drama of Hugo’s narrative, stripping away the melodies to focus intently on the dogged, decades-long pursuit that defines the core conflict.

A Conflict Carved in Stone

And what a conflict it is. Opposite Neeson stands Geoffrey Rush, hot off his Oscar win for Shine (1996), as Inspector Javert. Rush doesn't chew the scenery; he calcifies it. His Javert is a man not merely rigid, but seemingly forged from inflexible principle, his adherence to the law a terrifying absolute. The scenes between Neeson and Rush crackle with unspoken history and opposing worldviews. It’s not just cop-and-robber; it’s a philosophical battleground. You see it in Neeson's eyes – the hunted animal seeking peace – and in Rush's unwavering stare – the embodiment of a system that allows no deviation. Their dynamic is the engine of this adaptation, and it’s compelling precisely because it feels so grounded, so relentlessly human in its tragedy.

Danish director Bille August, already celebrated for works like the Palme d'Or winner Pelle the Conqueror (1987), brings a distinctly European sensibility. His approach is measured, visually rich, favoring atmosphere over histrionics. The film boasts a significant scale – reportedly budgeted around $50 million (a hefty sum for a period drama back then, maybe closer to $90-100 million today), which sadly didn't translate into box office success, barely scraping $14 million in the US. Perhaps the ghost of the musical loomed too large for audiences at the time? Regardless, the investment shows on screen. Filmed largely in the Czech Republic, with Prague standing in beautifully, if perhaps a little too cleanly, for 19th-century Paris, the production design creates a believable, albeit somber, world. There's a tangible quality to the mud, the poverty, the grandeur and the grime.

More Than Just the Main Event

While the Valjean/Javert duel dominates, the supporting cast adds crucial texture. Uma Thurman, post-Pulp Fiction (1994) cool, delivers a harrowing Fantine. Her screen time is tragically brief, mirroring the character's fate, but her portrayal of desperation and sacrifice lingers powerfully. It's a stark reminder of the societal cruelties Hugo railed against. Claire Danes, then known for My So-Called Life and Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet (1996), embodies the hope and innocence of Cosette, providing a necessary counterpoint to the surrounding darkness.

Rafael Yglesias's screenplay undertakes the Herculean task of condensing Hugo’s sprawling masterpiece. Necessarily, subplots are trimmed, characters streamlined. Some might miss the intricate social tapestry of the novel or the emotional peaks of the musical's anthems. This version is undeniably leaner, focusing squarely on Valjean's journey toward redemption and Javert's relentless pursuit. It’s a choice that yields a more direct, arguably more conventionally cinematic narrative, but one that still resonates with the core themes of mercy, justice, and the possibility of change. I recall renting this on VHS, perhaps expecting familiar refrains, but finding instead a somber, thoughtful drama that stayed with me in a different way.

Retro Fun Facts Woven In

It’s fascinating to think about the casting clout this film assembled in '98 – Neeson, Rush, Thurman, Danes – all major names. August’s decision to eschew the songs was bold, aiming for a definitive dramatic version. The use of Prague as a stand-in for Paris was a common cost-saving measure for historical epics of the era, but it speaks volumes about the logistics of recreating such specific period detail on location. This wasn't just another costume drama; it was a significant undertaking aiming for prestige.

Does it Hold Up on the Magnetic Tape of Time?

Watching Les Misérables (1998) today, removed from the initial comparisons and box office disappointment, allows its strengths to shine more clearly. It stands as a handsome, impeccably acted, and deeply serious adaptation. It doesn't aim for the soaring emotion of the musical, but instead offers a quieter, more introspective exploration of Hugo's enduring questions about human nature, societal structures, and the possibility of grace in a fallen world. Neeson’s performance remains a cornerstone, a compelling portrayal of a good man battling impossible circumstances.

Rating: 7.5/10

This score reflects a film that succeeds admirably in its specific goal: presenting a powerful, non-musical dramatic interpretation of a classic. The central performances by Neeson and Rush are outstanding, the production values are high, and August's direction is assured. It might lack the sheer emotional sweep some associate with the title, and the necessary narrative streamlining might frustrate purists, but its focused intensity and thoughtful approach earn it solid marks. It’s a testament to the power of Hugo’s story that it can sustain such different, yet equally valid, interpretations.

This Les Misérables may not be the version that prompts spontaneous singalongs, but it’s one that invites contemplation long after the VCR clicks off, leaving you pondering the weight of a single life caught in the gears of justice and mercy. A worthy resident of any discerning VHS shelf.