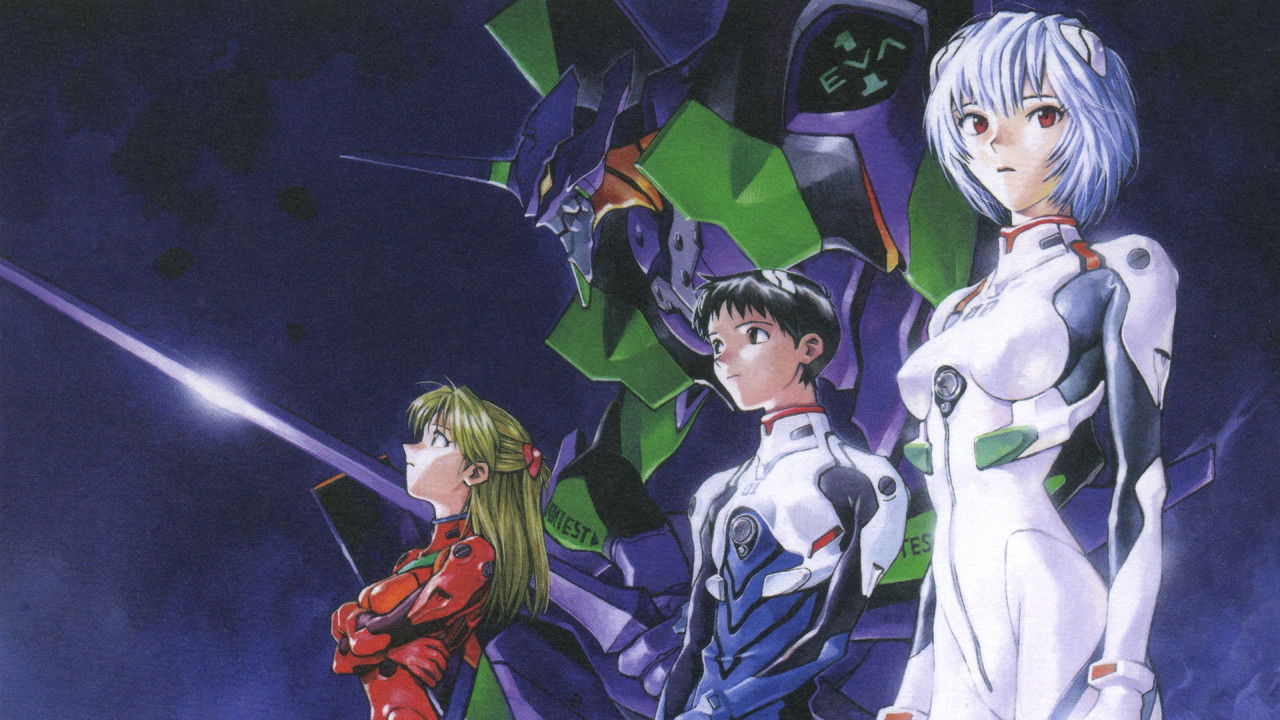

Some images burn themselves onto the back of your eyelids. They linger long after the static hiss of the stopping tape, shapes shifting in the darkness of a room lit only by the phantom glow of a switched-off CRT. For anyone who sought out Neon Genesis Evangelion beyond its challenging, debated television conclusion, the monstrous, beautiful, and utterly terrifying finality presented in Revival of Evangelion (1998) is likely one such indelible scar. This wasn't just an anime; it felt like witnessing a broadcast from the edge of the abyss.

A Necessary Apocalypse

Let's clear the static first. Revival of Evangelion isn't technically a single, new film. It's the theatrical package that combined the recap/re-edit Evangelion: Death(true)² with the soul-shattering The End of Evangelion. The latter, of course, was Hideaki Anno's direct, visceral response to the... polarizing reception of the original series' final two episodes. Fans felt cheated, confused, perhaps even abandoned by the introspective, budget-constrained conclusion. Anno, reportedly battling severe depression and feeling attacked by some segments of the fanbase (death threats were allegedly involved, a grim testament to the fervour surrounding the series), channeled that turmoil, frustration, and perhaps a desire for cathartic destruction, back onto the screen. The result, The End of Evangelion, forms the brutal heart of Revival, and it remains one of the most audacious, demanding, and unforgettable finales in animation history.

Congratulations? The Nightmare Begins

Forget giant robots punching monsters for a moment. While the Eva units and Angels are present, The End of Evangelion plunges headfirst into raw, psychological horror and existential dread. The relative safety of the NERV bunker dissolves into a charnel house as SEELE initiates its final, terrifying plan: Human Instrumentality. What follows is less a battle and more a prolonged, agonizing dissection of the human psyche under unimaginable pressure. We watch characters we've followed, flaws and all, utterly break down. Yūko Miyamura's performance as Asuka Langley Soryu reaches a fever pitch of defiance and despair in her desperate final stand, a sequence both exhilarating and deeply upsetting. And Megumi Ogata as Shinji Ikari... well, her vocal cords must have been shredded raw portraying Shinji's complete psychological collapse. Rumour has it Ogata was so immersed in Shinji's trauma during recording sessions, particularly the infamous hospital scene, that the lines blurred uncomfortably, lending an almost unbearable authenticity to his suffering.

The visuals are relentlessly inventive and disturbing. The escalating body count is depicted with unflinching, almost grotesque detail. But it's the surreal, apocalyptic imagery of Third Impact that truly sears itself into memory – the merging of souls, the giant, spectral Rei Ayanami (Megumi Hayashibara), the sea of LCL. It's abstract, terrifying, and loaded with symbolism that fans still debate decades later. Anno, alongside co-directors Kazuya Tsurumaki and Masayuki, uses every tool available – jarring cuts, shifts in animation style, unsettling sound design (Shirō Sagisu's score is iconic, perfectly balancing dread and operatic grandeur), and even a notorious sequence incorporating live-action footage – to confront and destabilize the viewer. This wasn't about providing easy answers; it felt like Anno was forcing us, alongside Shinji, to confront the ugliest parts of existence and the painful necessity of human connection, even if that connection inevitably leads to hurt.

Recap Before the Reckoning

The first part, Death(true)², serves as an elegant, albeit dense, recap of the original TV series, re-framing events through character perspectives and thematic lines. For newcomers, it’s likely impenetrable. For seasoned fans back in the day, it was a way to refresh the intricate plot points and emotional arcs before the main event. While perhaps less essential viewing now with the series readily available, its inclusion in Revival created a comprehensive, if lengthy, theatrical experience – a deep breath before the plunge. It set the mood, reminding us of the weight of trauma these characters carried before End utterly dismantled them.

Lingering Radiation

Watching Revival of Evangelion on a worn VHS tape, likely a treasured import or a carefully copied fan-sub back in the late 90s or early 2000s, felt like handling forbidden material. It was challenging, confusing, graphically violent, sexually charged in deeply uncomfortable ways, and philosophically dense. It didn't offer catharsis in the traditional sense; it offered psychic scarring, introspection, and a profound sense of unease. Did it 'fix' the TV ending? That's debatable. It certainly provided a more conventionally cinematic conclusion, but one steeped in such nihilism and pain that 'satisfying' feels like the wrong word entirely. Powerful? Undeniably.

Its influence is undeniable, pushing the boundaries of mainstream anime storytelling and demonstrating the medium's capacity for profound, adult psychological exploration. It cemented Evangelion not just as a popular mecha series, but as a cultural phenomenon and a deeply personal work of art born from its creator's struggles. Even the subsequent Rebuild of Evangelion film series, which offers an alternative (and some might say, more hopeful) path, exists in the long shadow cast by this monumental, terrifying conclusion.

***

Rating: 9/10

Justification: Revival of Evangelion, primarily through The End of Evangelion, is a landmark achievement in animation, albeit a deeply unsettling one. Its artistic ambition, raw emotional power, unforgettable imagery, and willingness to confront incredibly dark themes head-on are staggering. The sheer audacity of its vision, born from Hideaki Anno's personal crucible and fan reaction, is palpable. It loses a point only for the inherent density and the fact that Death(true)² feels somewhat less vital today, but the impact of End remains undiminished. It's demanding, often unpleasant, but utterly essential viewing for anyone serious about anime or confrontational filmmaking.

Final Thought: Decades later, the psychic residue of Third Impact still lingers. Revival of Evangelion wasn't just an ending; it was an event, a trauma, a masterpiece painted in shades of despair and desperate hope that few other works, animated or otherwise, have ever dared to match. It truly felt like the end of the world, viewed through the flickering static of a VCR.