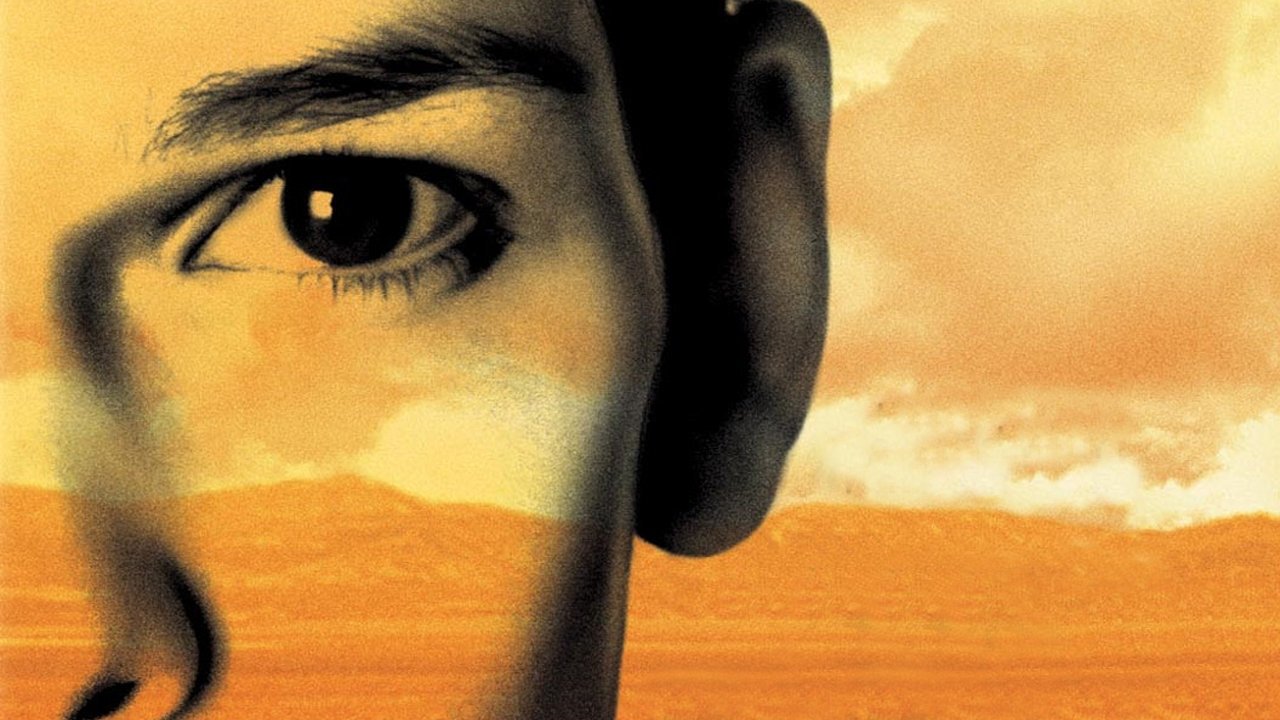

There are performances that lodge themselves under your skin, moving beyond mimicry into something unnervingly real. And then there is what Hilary Swank accomplishes in Kimberly Peirce’s shattering 1999 debut, Boys Don’t Cry. Watching it again after all these years doesn't diminish its power; if anything, the passage of time sharpens the edges of its tragedy, making the brief moments of joy feel even more precious, more fragile. This wasn't just another late-90s indie flick making waves; it felt like witnessing lightning captured in a bottle – raw, electrifying, and ultimately, devastatingly sad.

A Story That Demanded To Be Told

Based on the harrowing true story of Brandon Teena, a young trans man navigating life, love, and lethal prejudice in rural Nebraska, Boys Don't Cry doesn't flinch. Peirce, who spent years meticulously researching Brandon's life, including poring over court documents and interviewing those involved (a journey that began long before the acclaimed 1998 documentary The Brandon Teena Story brought wider attention), crafts a narrative that is deeply empathetic yet brutally honest. The film immerses us in the suffocating atmosphere of Falls City – the low-rent bars, the trailer parks, the endless, indifferent landscapes under that vast Midwestern sky. It's a world where dreams feel small and escape routes even smaller.

The story follows Brandon (Swank) as he arrives in this new town, quickly finding camaraderie and, crucially, romance with Lana Tisdel (Chloë Sevigny). Their connection forms the film's fragile heart – a bond built on shared desires for something more, a tentative hope blooming in desolate ground. But Brandon's secret, the fact that he was assigned female at birth, hangs like a Sword of Damocles over their burgeoning happiness, particularly as he falls deeper into the orbit of Lana's ex-convict friends, the volatile John Lotter (Peter Sarsgaard) and Tom Nissen (Brendan Sexton III).

Inhabiting Truth: Swank and Sevigny

It’s impossible to discuss Boys Don’t Cry without focusing on the performances, particularly Swank's. Her transformation is staggering, not just physically – the bound chest, the swagger, the lower vocal register – but emotionally. She inhabits Brandon's yearning, his infectious charm, his desperate hope for acceptance, and his paralyzing fear. There's a vulnerability beneath the assumed masculinity that makes his eventual fate all the more heartbreaking. It’s a performance devoid of caricature, grounded in a profound understanding of the character's inner life.

One compelling piece of trivia often shared is how Swank lived as a man for a month before filming began, cutting her hair short and binding her chest, even introducing herself to strangers as Hilary's brother, James. Her dedication was such that neighbors reportedly believed a young man was visiting her husband. This wasn't mere method acting indulgence; it seems to have been crucial for her to access the bone-deep authenticity that radiates from the screen. Reportedly paid just $75 a day for her work, totaling around $3,000 for the entire shoot, her Oscar win feels like cosmic justice for such a committed, soul-baring portrayal. Peirce herself initially had doubts, considering Swank "too girly," but Swank's relentless pursuit of the role ultimately won her over.

Equally vital is Chloë Sevigny as Lana. Already an indie icon thanks to films like Kids (1995) and Gummo (1997), Sevigny brings a captivating mix of world-weariness and naive hope to Lana. She’s drawn to Brandon's gentle spirit, a stark contrast to the aggressive masculinity surrounding her. The chemistry between Swank and Sevigny is palpable, their scenes together offering fleeting moments of warmth and genuine tenderness amidst the encroaching dread. Sevigny masterfully conveys Lana’s confusion, attraction, and eventual devastation without resorting to histrionics. Her performance earned her a well-deserved Oscar nomination, grounding the film's central relationship in relatable emotional truth. And Peter Sarsgaard, in one of his early prominent roles, is terrifyingly convincing as John Lotter, embodying a casual menace that chills to the bone.

Peirce's Unflinching Gaze

For a debut feature, Peirce's direction is remarkably assured. She demonstrates a keen eye for capturing the textures of this specific environment and the complex dynamics within it. The film, shot mostly in Texas standing in for Nebraska on a tight budget (around $2 million, a testament to indie resourcefulness which impressively grossed over $20 million worldwide), feels immediate and lived-in. Peirce doesn't shy away from the story's inherent brutality, particularly in the devastating final act, but she handles it with a sensitivity that avoids gratuitousness. The violence serves the narrative, highlighting the horrific consequences of ignorance and hate, rather than exploiting them. The way the camera often lingers on faces, capturing unspoken emotions, draws us deeper into the characters' experiences. What lingers most after the film ends? Perhaps it's the stark realization of how quickly fragile hopes can be extinguished by ingrained prejudice.

Legacy in Celluloid

Boys Don't Cry arrived at a critical juncture, significantly contributing to the visibility of transgender stories in mainstream(ish) cinema, albeit through a tragic lens. It sparked conversations, challenged assumptions, and showcased the immense talent of its cast and director. While discussions around representation have evolved significantly since 1999, particularly regarding cisgender actors playing transgender roles, the film's raw power and emotional honesty remain undeniable. It stands as a landmark piece of late-90s independent filmmaking, a difficult but essential watch that forces viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about identity, acceptance, and the devastating impact of intolerance. Doesn't the core struggle for understanding and safety depicted here still resonate with challenges faced today?

---

Rating: 9/10

Justification: Boys Don't Cry earns a 9 primarily due to the monumental, transformative performances from Hilary Swank and Chloë Sevigny, which remain utterly compelling and deeply affecting. Kimberly Peirce's sensitive yet unflinching direction, especially for a debut, masterfully crafts an atmosphere of both tender intimacy and suffocating dread. The film's courage in tackling its difficult subject matter with raw honesty and empathy was groundbreaking for its time and still resonates powerfully. While the inherent bleakness makes it a challenging viewing experience, its importance as a piece of cinematic history and its sheer emotional impact are undeniable. It falls just short of a perfect score perhaps only because the relentless tragedy can feel overwhelming, leaving little room for nuanced exploration of supporting characters beyond their roles in Brandon's fate, though this focus is arguably central to the film's intent.

Final Thought: This isn't a film you revisit lightly, like slipping in a favorite action flick. Boys Don't Cry demands something from you, leaving an indelible mark – a stark, poignant reminder, preserved from the cusp of the millennium, of the human cost of hate and the desperate, enduring need for acceptance.