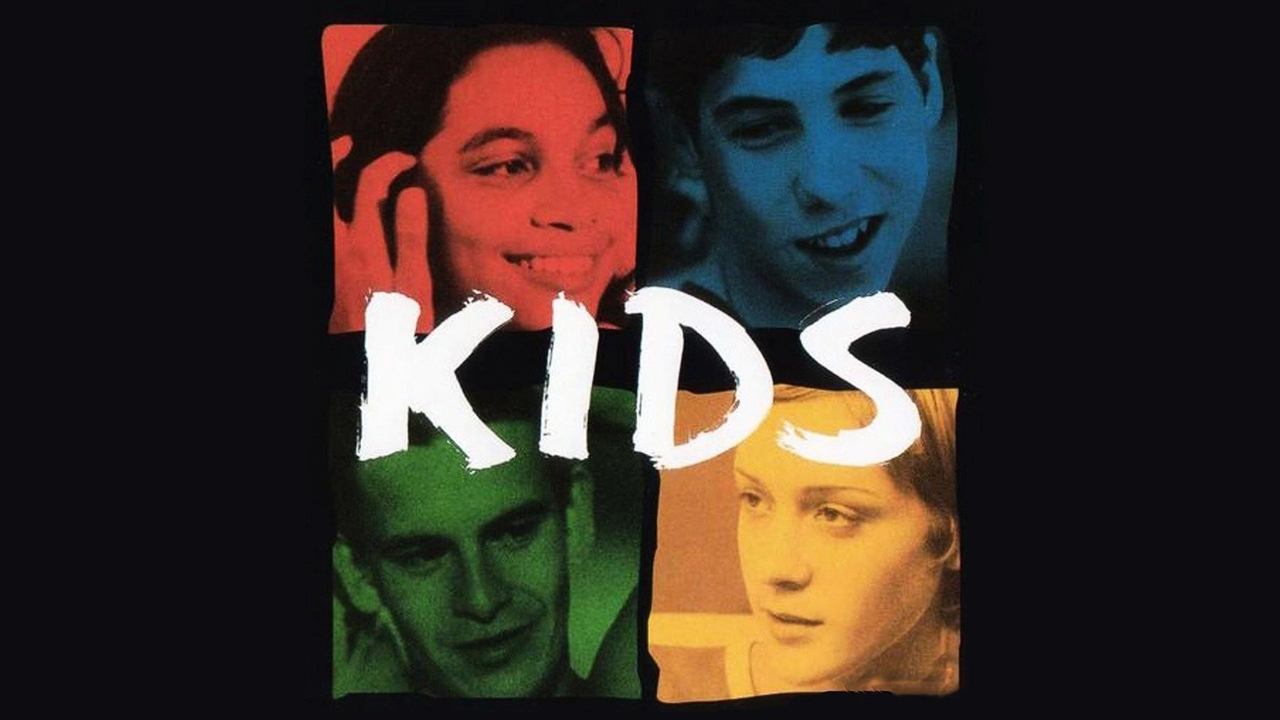

It hits you not like a film, but like a documentary smuggled out from a world you suspected existed but perhaps hoped didn't, at least not with such raw, unfiltered intensity. Larry Clark's Kids (1995) wasn't just another movie on the shelf at Blockbuster; pulling that tape felt like an act of transgression in itself. There was a buzz around it, whispers of controversy, the stark black and white cover art hinting at something far removed from the usual teen comedies or dramas of the era. It promised a glimpse into the abyss, and frankly, it delivered.

A Day Like Any Other, Except It Isn't

The premise is deceptively simple: follow a group of New York City teenagers over the course of a single, sweltering summer day. But within that 24-hour window, writer Harmony Korine (famously just 19 when he wrote the screenplay, lending it an unnerving, contemporary voice) and director Clark unpack a Pandora's box of casual sex, drug use, petty crime, and profound aimlessness. Our primary guides are Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick), a self-proclaimed "virgin surgeon" whose predatory monologues are chilling in their nonchalance, and his best friend Casper (Justin Pierce), swept along in the same current of nihilistic hedonism. Hovering on the periphery, and eventually becoming central to the film's devastating undertow, is Jennie (Chloë Sevigny in a startling debut), whose discovery about her own health status provides the narrative's ticking clock.

There's an immediacy to Kids that still feels potent. Clark, bringing the unflinching eye he honed as a photographer chronicling volatile youth culture in works like Tulsa and Teenage Lust, largely eschews traditional narrative structure. Much of the film feels observational, almost cinéma vérité, dropping us directly into conversations laced with authentic slang and deploying handheld camerawork that mirrors the characters' restless energy. This wasn't Hollywood pretending to be gritty; this felt like the genuine article, rough edges and all.

Casting Lightning in a Bottle

A huge part of that authenticity stems from the casting. Clark populated the film primarily with non-professional actors, real NYC skateboarders and teenagers scouted from Washington Square Park. Leo Fitzpatrick embodies Telly with a terrifying lack of self-awareness, making him not a cartoon villain but a disturbingly plausible product of his environment. The late Justin Pierce, himself a gifted skateboarder, brings a tragic vulnerability to Casper, a kid seemingly aware of the downward spiral but unable or unwilling to break free. And Chloë Sevigny, even then, possessed a captivating screen presence, conveying Jennie's dawning horror and quiet desperation with minimal dialogue. Her performance anchors the film's emotional core, fragile as it is. You also spot a very young Rosario Dawson among the group, another remarkable debut foreshadowing a significant career.

Getting this raw portrayal onto screens wasn't easy. Financed independently for around $1.5 million after established studios balked, the film inevitably clashed with the MPAA, receiving the dreaded NC-17 rating. Rather than cut the film, distributors Miramax and the newly formed Shining Excalibur Films opted to release it unrated, a move that only amplified its notoriety and likely contributed to its eventual $20 million-plus box office haul – a significant return for such challenging material. It became a cultural flashpoint, debated endlessly for its perceived exploitation versus its undeniable power as a wake-up call.

The Uncomfortable Mirror

Watching Kids today, especially through the lens of VHS nostalgia, is a complex experience. The grainy image quality, the specific 90s fashion and music – it transports you back. But the film's core themes remain unsettlingly relevant. It forces a confrontation with uncomfortable truths about adolescent sexuality, peer pressure, the dangers of apathy, and the devastating consequences that can ripple outwards from seemingly casual decisions. The backdrop of the AIDS crisis looms large, not through overt preaching, but through Jennie's personal catastrophe, making Telly's boasts feel even more grotesque.

Did Clark and Korine merely observe, or did they exploit? It's a question that has followed the film since its release. There’s no easy answer. The film offers no judgment, no neat moral conclusions. It simply presents this world, these characters, and leaves the viewer to grapple with the profound unease it generates. Is Telly solely responsible, or is he a symptom of a larger societal disconnection, of absent parents and absent futures? What does Jennie’s fate say about the vulnerability lurking beneath bravado? These aren't comfortable questions, and Kids refuses to provide comfortable answers.

Legacy of Unease

It’s not a film one "enjoys" in the conventional sense. There’s no catharsis, no uplift. Yet, its impact is undeniable. It launched careers, sparked vital (if difficult) conversations, and pushed the boundaries of mainstream American filmmaking. It stands as a stark, divisive artifact of the mid-90s, a time capsule filled not with comforting nostalgia, but with the anxieties and dangers simmering beneath the surface of youth culture.

Rating: 8/10

This high rating reflects the film's sheer, visceral impact, its technical execution in achieving a raw, documentary feel, and its cultural significance, rather than traditional entertainment value. The performances, particularly from the non-professional cast and Sevigny, are remarkably authentic. Clark’s direction is unflinching and purposeful, even if the subject matter is deeply disturbing. It’s a film that achieves precisely what it sets out to do: provoke, disturb, and refuse to be ignored. It’s difficult viewing, yes, but its power as a piece of confrontational cinema is undeniable.

Kids remains a film that burrows under your skin. Decades later, the humid haze of that New York summer day and the chilling emptiness in Telly's eyes still linger, a potent reminder of the darkness that can hide in plain sight.