### The Lingering Silence of the Hospitality Suite

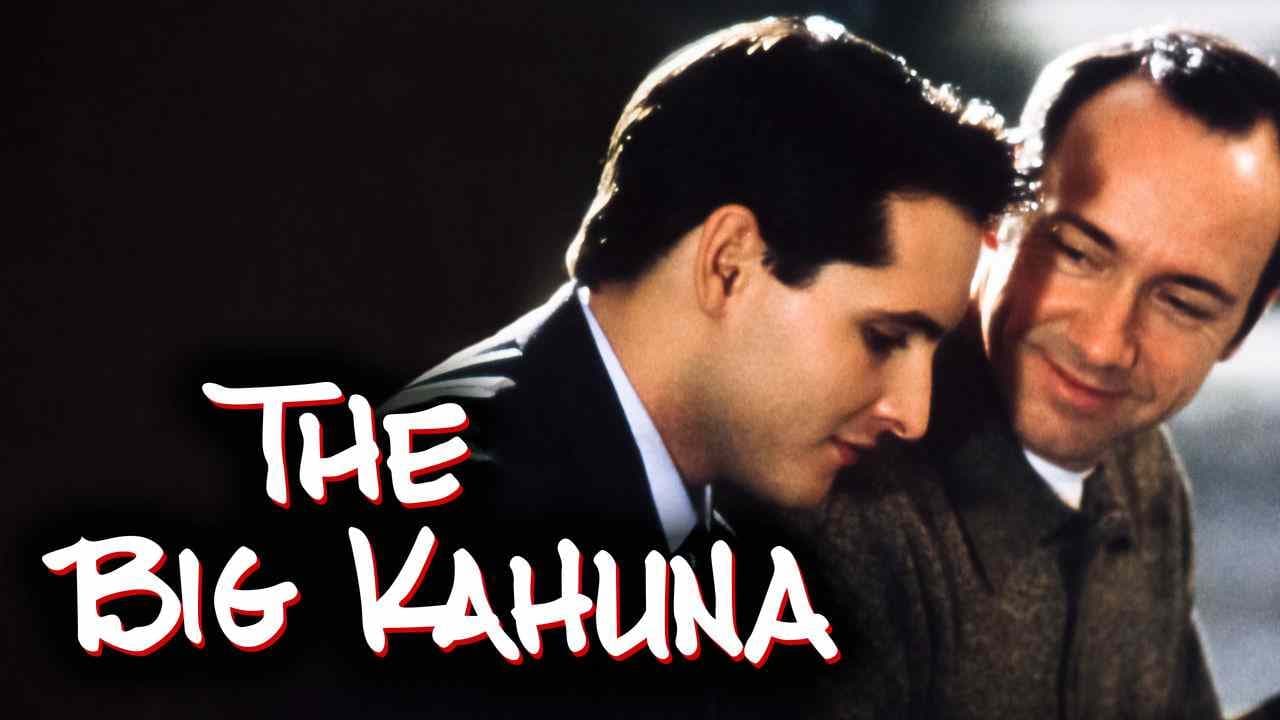

Sometimes a film settles over you not with a bang, but with the quiet weight of truths spoken in hushed tones, under the hum of hotel air conditioning. The Big Kahuna (1999) is one such film. It arrived near the turn of the millennium, a time when flashy blockbusters still dominated the multiplex, yet here was this contained, dialogue-driven piece that felt more like stumbling into an intense late-night conversation than watching a typical movie. I remember finding the VHS, likely nestled in the 'Drama' section, its cover art hinting at corporate intrigue but delivering something far more introspective. It’s a film that doesn't shout; it questions.

Adapted by Roger Rueff from his own 1992 stage play, "Hospitality Suite," the film wisely retains its theatrical intensity. Director John Swanbeck, in his feature debut, confines us almost entirely to a single Wichita hotel suite during a lubricant manufacturers' convention. This isn't just a budgetary constraint; it becomes a pressure cooker. We're trapped with three salesmen – Larry Mann (Kevin Spacey), Phil Cooper (Danny DeVito), and Bob Walker (Peter Facinelli) – representing a mid-level industrial lubricant company. Their mission: land the "Big Kahuna," the CEO of a major potential client whose account could save their struggling firm.

Character Over Commerce

What unfolds isn't really about lubricants or sales tactics, though those are the catalysts. It’s about the interplay between these three men, each representing a different stage of life and disillusionment. Kevin Spacey, riding high on his late 90s acclaim from films like American Beauty (1999) and L.A. Confidential (1997), delivers a masterclass in controlled volatility as Larry. He’s the sharp-tongued cynic, driven, laser-focused on the sale, masking deeper frustrations beneath layers of aggressive confidence. His performance is precise, capturing the brittle energy of a man who believes success is the only measure of worth. It's fascinating to note that Spacey's own production company, Trigger Street Productions, helped bring this to the screen, suggesting a personal connection to the material.

Contrast him with Danny DeVito's Phil. Often known for broader comedic roles like in Twins (1988) or his directing work on Matilda (1996), DeVito here offers perhaps one of his most soulful and understated performances. Phil is the veteran, weary but humane, recently divorced, grappling with his faith and the creeping realization that professional achievements might be hollow victories. DeVito imbues Phil with a profound sense of quiet decency and resignation. There's a weight in his posture, a searching look in his eyes that speaks volumes more than any sales pitch. He carries the film's moral center, reminding us (and Larry) that human connection transcends business.

Rounding out the trio is Peter Facinelli as Bob, the earnest, devoutly religious newcomer. He’s naive, optimistic, and possesses an guileless sincerity that initially grates on Larry but intrigues Phil. Facinelli effectively portrays Bob's journey from wide-eyed recruit to someone forced to confront the ethical compromises and existential questions the night throws at him. The tension between Larry's aggressive secularism and Bob's unwavering faith provides much of the film's philosophical underpinning.

From Stage to Screen

The film's stage origins are palpable. The action is confined, the dialogue is dense and central, and the focus is squarely on character interaction. While some critics at the time found it overly "stagey," I'd argue that this containment is precisely its strength. It forces us to lean in, to listen to the nuances in the conversation, the pauses, the things left unsaid. Swanbeck uses the claustrophobic setting effectively, emphasizing the emotional and professional pressure bearing down on the characters. There are no car chases, no explosions – the drama is entirely internal, playing out on the actors' faces and in the shifting dynamics within the room. This approach likely contributed to its modest $3.7 million box office against a reported $7 million budget, but it also cemented its status as a hidden gem for those seeking thoughtful drama.

One piece of trivia that highlights the transition is how Rueff adapted his own work. Plays often rely purely on dialogue, but film allows for visual storytelling, even in a confined space. Notice the way the camera frames the characters, sometimes isolating them, sometimes forcing them together, mirroring their emotional states. It’s subtle work, but effective.

The Questions That Linger

The Big Kahuna doesn't offer easy answers. It asks uncomfortable questions about integrity, ambition, faith, and what truly constitutes a meaningful life. Larry’s climactic monologue about missed opportunities and the importance of character – "It doesn't matter whether youaitaith is based on the Bible, or the Koran, or the phone book" – is a powerful piece of writing and acting, even if it comes from the least likely messenger. Does landing the big account truly satisfy, or is it the fleeting moments of genuine human connection, like the conversation Bob has with the CEO about his dog, that hold real value? What does it profit a man, the film seems to ask, if he gains the whole world but loses his soul... or maybe just forgets to ask about the dog?

It’s a film that resonates differently now, perhaps, viewed through the lens of subsequent decades and career trajectories. But its core examination of humanity within the often-dehumanizing confines of corporate life remains potent. It’s a reminder of those quieter films, often found lurking on the video store shelves, that prioritized conversation and character above spectacle.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the powerhouse performances, particularly from Spacey and DeVito, the intelligent script adapted beautifully from its stage origins, and its willingness to tackle profound themes within a deceptively simple setup. While its contained nature might feel slow to some, it rewards patient viewing with genuine insight. It might not have been the blockbuster of '99, but The Big Kahuna remains a significant, thought-provoking character study.

It leaves you pondering not the fate of the lubricant company, but the quiet battles waged within each of us between ambition and authenticity, cynicism and hope. A true conversation starter, even decades later.