It’s 1945, Moscow. The Great Patriotic War has scarred the landscape and the people, but the fight isn't over. A different kind of battle rages in the shadows, a war against the brutal "Black Cat" gang whose brazen crimes terrorize a city desperate for peace. This is the grim, electric backdrop for Stanislav Govorukhin's masterful 1979 Soviet miniseries, The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed (Место встречи изменить нельзя), a sprawling, morally complex detective story that, even decades later, feels astonishingly potent. For many of us who discovered it later, perhaps on a multi-generational VHS copy passed between enthusiasts, it was a revelation – a window into a different world of filmmaking, yet tackling universal questions of justice, duty, and the marks war leaves on the soul.

### Echoes in the Rubble

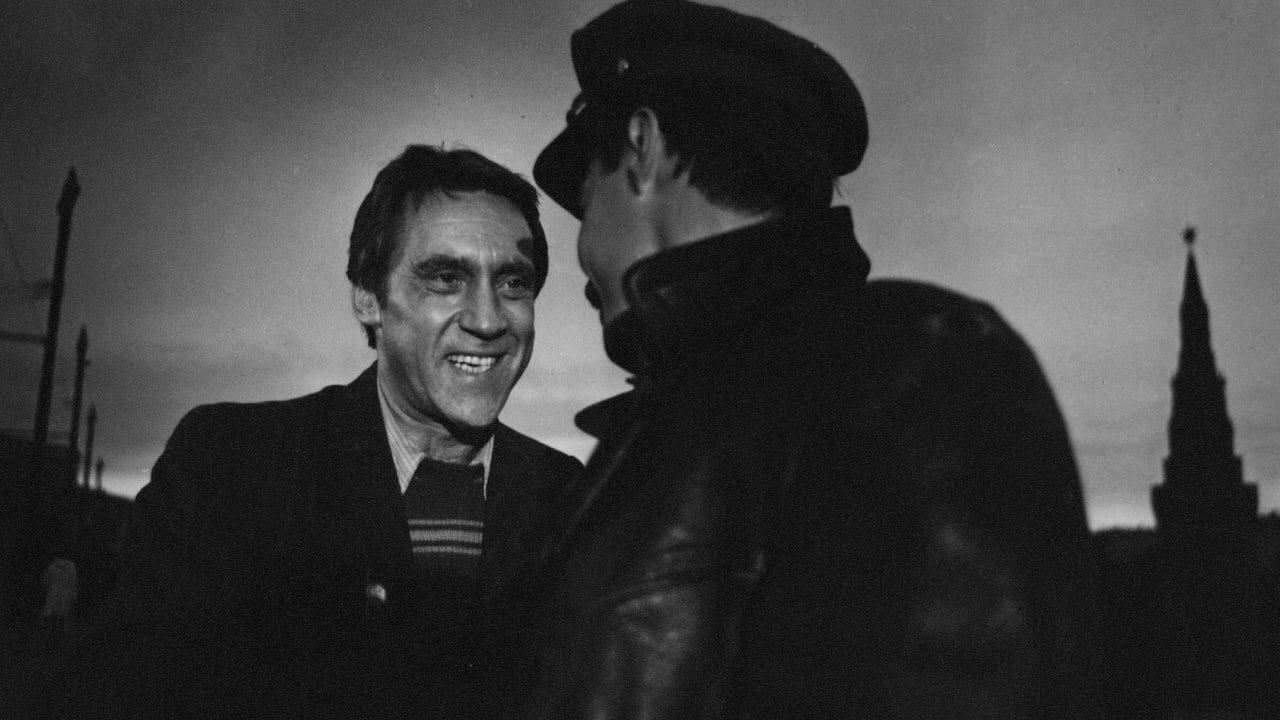

What strikes you immediately is the atmosphere. Govorukhin, working from the novel "Era of Mercy" by the Vayner brothers (who also co-wrote the screenplay), doesn't just depict post-war Moscow; he makes you feel its weariness, its lingering tension, the palpable sense that beneath the surface of relief, danger still lurks. The black and white cinematography (though originally shot in color, it was broadcast and largely remembered in monochrome, enhancing its noirish feel) adds to the starkness. There’s little glamour here; just rain-slicked streets, cramped communal apartments, and the imposing halls of the Moscow Criminal Investigations Department (MUR). Recreating this specific moment in time wasn't simple; filming often relied on finding pockets of the city that hadn't changed much, or cleverly obscuring modern intrusions – a testament to the resourcefulness of the production.

### The Lawman and the Idealist

At the heart of the series are two unforgettable figures, detectives whose contrasting methods form the film's ideological core. Gleb Zheglov, played with ferocious charisma by the legendary singer-songwriter Vladimir Vysotsky, is the seasoned, cynical, results-driven cop. He’s charming when he needs to be, utterly ruthless when he feels justified, bending rules and planting evidence if it means getting the ‘scum’ off the streets. His philosophy is stark: "A thief's place is in prison!" (Вор должен сидеть в тюрьме!), a line that became instantly iconic across the Soviet Union. Vysotsky embodies Zheglov with a raw energy that crackles off the screen; it’s a force-of-nature performance, making you understand his motivations even as you question his methods. It's hard to fathom now, but the studio initially had reservations about casting Vysotsky, preferring more conventional film actors. It was Govorukhin's insistence, backed by Vysotsky's immense off-screen popularity, that secured him the role – a decision that cemented the series' place in history.

Counterpointing Zheglov is the younger, idealistic Volodya Sharapov (Vladimir Konkin), a former frontline reconnaissance officer new to police work. He’s intelligent, principled, and deeply troubled by Zheglov’s willingness to operate outside the law. Sharapov believes in due process, in the importance of evidence and the letter of the law. Konkin portrays Sharapov’s quiet integrity and moral struggle beautifully, providing the essential conscience of the story. Their relationship – a mix of grudging respect, mentorship, and fundamental conflict – is utterly compelling. Doesn't their dynamic raise timeless questions about policing itself? How much compromise is too much in the pursuit of justice?

### More Than Just a Procedural

While the hunt for the Black Cat gang provides the narrative engine – complete with undercover operations, tense interrogations, and sudden bursts of violence – The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed offers so much more than a standard police procedural. It’s a rich tapestry of post-war life, populated by vivid supporting characters, each carrying their own burdens and secrets. From the weary expertise of the forensics team to the desperate lives of small-time crooks and the palpable fear of ordinary citizens, the series paints a detailed, human portrait of a society rebuilding itself. The sheer length of the miniseries (originally aired in five parts) allows for this depth, letting moments breathe and characters develop organically.

One can only imagine the impact this had on its initial audience. When it first aired in November 1979, reports claimed streets emptied as families gathered around their televisions. Its blend of thrilling crime story, complex characters, and authentic period detail resonated deeply, making it an enduring cultural touchstone. For those of us discovering it later via worn VHS tapes, it felt like uncovering a hidden classic, a piece of powerful storytelling that transcended language and borders. Watching Vysotsky, knowing he tragically passed away less than a year after the series aired, adds another layer of profound poignancy to his definitive performance.

### The Verdict

The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed isn't just a brilliant detective series; it's a significant piece of television history. Its exploration of morality, the ambiguity of its hero, the textured portrayal of its setting, and the powerhouse performances, especially from Vladimir Vysotsky, make it unforgettable. It avoids easy answers, forcing viewers to grapple with difficult questions long after the credits roll. The pacing might feel deliberate compared to modern thrillers, but its depth and atmosphere are rewards in themselves. Finding a good subtitled version might take a little digging, but believe me, it’s worth the effort. This is essential viewing for anyone interested in crime drama, Soviet-era cinema, or simply powerful, character-driven storytelling.

Rating: 9.5/10

It’s a near-perfect execution of its ambition, held back only slightly by the inherent limitations of its television origins compared to big-screen features of the era. Yet, its thematic weight and unforgettable lead performance elevate it far beyond those constraints. What lingers most is the haunting question: in the fight against darkness, how do we keep from becoming consumed by it ourselves?