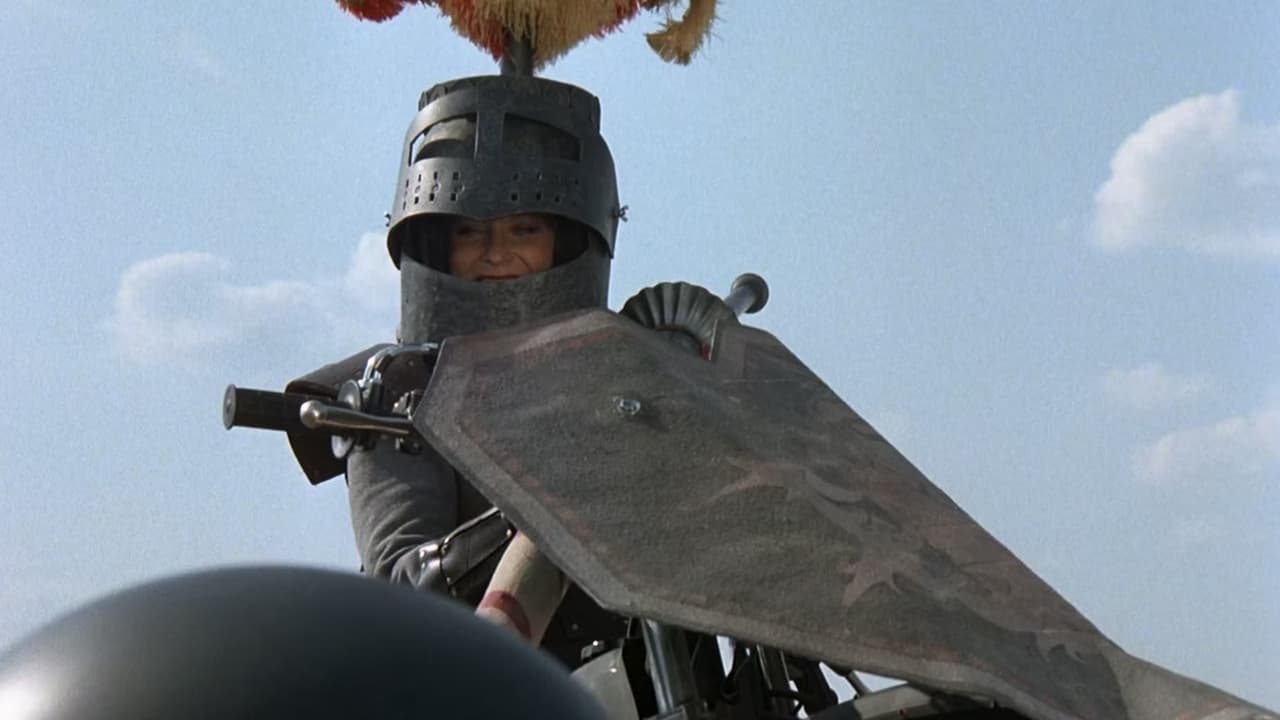

It’s a strange vision, isn't it? Knights in dented armor, lances lowered, not astride warhorses but astride gleaming, roaring motorcycles. This central image of George A. Romero's Knightriders (1981) is potent, maybe even slightly absurd at first glance. Finding this tape on a rental shelf back in the day, nestled perhaps near Romero's more famous zombie outings, felt like uncovering a secret – something utterly unexpected from the master of the undead. And revisiting it now? It feels less like an oddity and more like a deeply personal, almost melancholic statement from a filmmaker wrestling with ideals in a world leaning hard towards compromise.

### More Than Just Medieval Motorbikes

Forget the easy categorization. Knightriders isn't really an action film, though it features impressive motorcycle jousting (much of it performed by the actors themselves, including a fiercely committed Ed Harris). It’s not quite a fantasy, despite its Arthurian trappings. At its heart, this is George A. Romero, the man who gave us Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead, crafting a character drama about integrity, community, and the corrosive influence of commercialism. It’s a film that asks: can you live by a code, a chosen set of ideals, when the modern world demands you sell out or fade away?

The film follows a travelling Renaissance Faire troupe led by Billy (Ed Harris), who insists on living by a strict Arthurian code, referring to himself as King William. His knights, including the charismatic but pragmatic Morgan (Tom Savini, Romero’s frequent collaborator and legendary makeup effects artist), perform medieval combat on motorcycles for rural crowds. But tensions simmer. Local law enforcement views them with suspicion, internal conflicts fester over leadership and loyalty, and the lure of bigger audiences and slicker promotion threatens to shatter the very principles Billy holds dear.

### The Weight of the Crown

Ed Harris, in one of his earliest leading roles, is nothing short of magnetic. He doesn't just play Billy; he embodies the man's burning intensity, his unwavering belief in the code, and the immense pressure that comes with it. There’s a scene where Billy, wrestling with his doubts and the physical toll of his role, deliberately injures himself – it’s raw, unsettling, and speaks volumes about the character's internal struggle. Harris reportedly threw himself into the role with similar fervor, performing many of his own stunts and capturing that sense of a man trying to hold onto an ideal that might be slipping through his fingers. Is his rigidity noble, or is it a fatal flaw? The film leaves that satisfyingly ambiguous.

Contrast this with Tom Savini's Morgan. He’s not inherently evil, but he represents the seductive path of pragmatism. Why stick to muddy fields and small crowds when national exposure beckons? Savini, known more for his groundbreaking gore effects in films like Friday the 13th and Dawn of the Dead, proves himself a capable actor here, portraying Morgan's ambition and eventual break with Billy with believable conviction. Their conflict forms the ideological spine of the film.

### Romero's Personal Quest

Romero himself often cited Knightriders as his most personal film. Shot around his native Pittsburgh for about $3.7 million (a modest sum even then, roughly $12 million today), it feels like a departure, yet the themes resonate with his other work. Just as his zombies often served as metaphors for mindless consumerism or societal breakdown, the challenges faced by Billy's troupe reflect the struggle of independent artists (like Romero himself) trying to maintain their vision against commercial pressures. The film reportedly stemmed from Romero witnessing a Society for Creative Anachronism event and pondering the dedication required to live out such fantasies.

The production itself had its share of real-world grit. Integrating the complex motorcycle stunts safely was a major undertaking, coordinated in part by Savini. And look closely during the fair scenes – you might spot horror author Stephen King (a friend and collaborator of Romero's) making a brief, hilarious cameo as the wonderfully named "Hoagie Man," offering commentary from the crowd. It’s one of those delightful "VHS pause button" moments for fans. Apparently, King’s wife Tabitha also appears briefly as his on-screen spouse. These little touches add to the film's authentic, lived-in feel. Despite its ambition, the film sadly didn't find a large audience initially, barely recouping its budget at the box office, perhaps because audiences expecting another Romero horror spectacle were baffled by this medieval motorcycle drama.

### A Community Under Siege

Beyond the central conflict, Knightriders excels at portraying the messy, complex dynamics of this chosen family. We see the loyalty, the love, the petty jealousies, and the genuine bonds forged through shared experience and belief. Gary Lahti as Alan, Billy's cousin and conflicted second-in-command, and Amy Ingersoll as Linet, Billy's queen torn between loyalty and practicality, add layers to the human drama. It’s not just about knights and bikes; it's about people trying to build something meaningful together, and the internal and external forces that threaten to tear it apart. Does the weight of upholding an ideal inevitably crush the community built around it?

The film isn't perfect. At nearly two and a half hours, its pacing can feel ponderous at times, dwelling perhaps a little too long on certain character beats or philosophical debates. Some moments might strike modern viewers as overly earnest or melodramatic. Yet, its sincerity is also its strength. It never winks at its own premise. It takes the ideals, the conflicts, and the characters seriously, inviting us to do the same.

### Lasting Echoes of the Roaring Knights

Knightriders remains a unique entry in George A. Romero's filmography and a fascinating artifact of early 80s independent filmmaking. It’s a film with mud on its boots and grease on its chainmail, tackling themes of artistic integrity, the allure of fame, and the struggle to live authentically in a world that often rewards conformity. It’s the kind of discovery that made browsing those video store aisles so rewarding – unexpected, ambitious, and deeply felt.

Rating: 8/10

Its length and occasional earnestness might test some viewers, but Knightriders earns this score through its sheer audacity, Ed Harris's powerhouse performance, its surprisingly resonant themes, and its status as a truly unique vision from a master filmmaker stepping outside his expected genre. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most compelling quests are the ones fought not with swords, but with conviction, even atop a roaring motorcycle. What code do you choose to live by, it seems to ask, long after the engines have quieted?