There’s a particular kind of quiet intensity that some films possess, an atmosphere that settles over you long after the tape has clicked off in the VCR. Andrei Konchalovsky’s Maria’s Lovers (1984) is precisely that kind of film. It doesn't shout its themes from the rooftops; instead, it lets them steep, like strong tea, in the melancholic air of post-war Pennsylvania. What lingers most, perhaps, is the haunting gaze of Nastassja Kinski, embodying a complex blend of loyalty, desire, and simmering frustration that feels startlingly real.

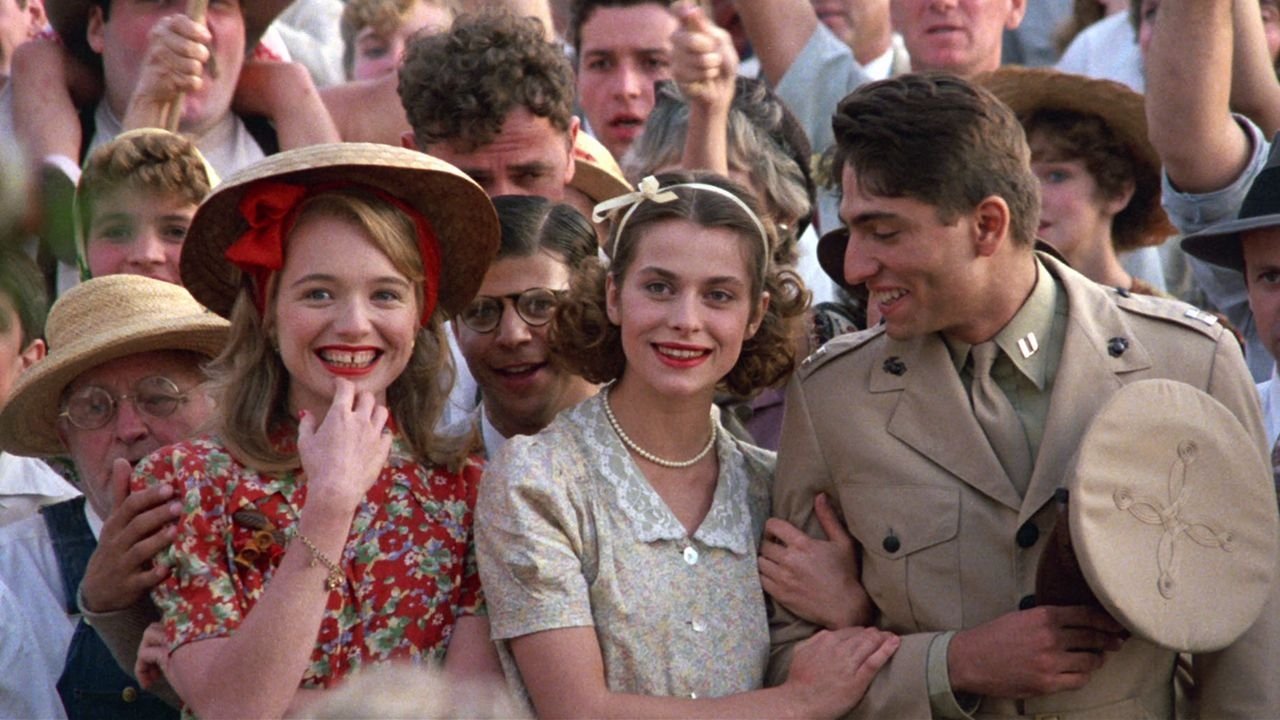

Set against the backdrop of a small, working-class town grappling with the return of its soldiers from World War II, the film centers on Ivan Bibic (John Savage), a man deeply scarred by his experiences as a prisoner of war. He comes home a hero, carrying the idealized image of Maria (Nastassja Kinski) – the neighborhood beauty he worshipped from afar – as the beacon that kept him alive. They marry quickly, swept up in the relief and expectation of homecoming. But the war has left deeper wounds than anyone acknowledges, manifesting in a crippling impotence that prevents Ivan from consummating his marriage with the very woman who symbolized his survival.

The Scars We Carry

This central conflict – Ivan’s inability to connect physically with Maria despite his profound love for her – is the raw, beating heart of the film. It’s a brave and difficult subject, particularly for a mid-80s American movie, exploring what we now readily identify as PTSD. John Savage throws himself into the role with a harrowing intensity. His Ivan is a man coiled tight with shame, confusion, and a love so fierce it paradoxically pushes Maria away. It’s not always an easy performance to watch; Savage internalizes much of Ivan’s torment, sometimes bordering on inscrutable, but the pain radiating from him is undeniable. Doesn't his struggle force us to consider how ill-equipped society often is to handle the invisible burdens soldiers bring home?

It’s fascinating to note this film came from Cannon Films, a studio more often associated with the high-octane exploits of Chuck Norris or Charles Bronson! Golan-Globus producing a sensitive character drama directed by a Soviet émigré (Andrei Konchalovsky, who would direct the fantastic Runaway Train for Cannon just a year later) feels like a delightful anomaly from the VHS era. Konchalovsky, working with screenwriters including Gérard Brach (a frequent collaborator with Roman Polanski), brings an outsider’s perspective, capturing the textures of American life – the close-knit community, the looming factories, the quiet desperation – with a poet’s eye. The film was shot on location in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, and that authenticity grounds the story beautifully. You can almost feel the grit and humidity of that specific place and time.

A Woman Caught Between Worlds

While Ivan’s trauma drives the plot, it’s Nastassja Kinski’s Maria who provides the film’s emotional anchor. Kinski, already an international star thanks to films like Tess (1979) and Cat People (1982), is luminous here. She embodies Maria’s deep loyalty to Ivan, her confusion at his rejection, and the burgeoning awareness of her own desires. There’s a quiet strength in her portrayal; she’s no mere victim waiting for Ivan to heal. She has agency, needs, and a burgeoning sensuality that attracts others, most notably the charming, guitar-strumming wanderer Clarence (Keith Carradine, effortlessly charismatic). Carradine offers Maria a vision of uncomplicated affection, a stark contrast to the tortured love Ivan provides. How does Maria navigate this impossible situation? Kinski makes her choices feel earned, rooted in a genuine, complex inner life.

And then there’s Robert Mitchum. As Ivan’s father, Mitchum arrives late in the film, but his presence is immense. He brings that world-weary gravitas only a screen legend truly can. His scenes with Savage are electric, offering gruff, pragmatic wisdom that cuts through Ivan’s self-pity. It’s a reminder of Mitchum’s incredible range, adding layers of patriarchal expectation and unspoken understanding to the already complex family dynamics. His brief appearance feels like a grounding force, connecting the film's specific post-war anxieties to a longer, more timeless story of fathers and sons.

Love, Loyalty, and the Long Road Home

Maria’s Lovers isn't a film that offers easy answers. It delves into the messy realities of love when confronted with deep trauma. Can love conquer all, even the horrors of war imprinted on the soul? How much loyalty does one owe to a partner who cannot meet their needs? Konchalovsky doesn't shy away from the pain, but he also doesn't wallow in it. There's a deep empathy for all the characters, even in their flawed choices. The film explores the pressure cooker of small-town life, where everyone knows everyone's business, adding another layer of difficulty to Maria and Ivan's private struggle.

The pacing is deliberate, allowing the mood and characters to breathe. It might test the patience of viewers expecting typical 80s melodrama, but the reward is a richer, more resonant experience. It feels like finding one of those unexpected gems on the video store shelf, nestled between the blockbusters – a film that stays with you, prompting reflection on the enduring power of love and the long shadows cast by conflict.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's powerful performances, particularly from Kinski and Mitchum, its sensitive handling of difficult themes, and Konchalovsky's atmospheric direction. While Savage’s intense portrayal might be divisive for some, and the pacing is measured, the film’s emotional honesty and refusal of easy sentimentality make it a standout drama from the era. It's a thoughtful, beautifully crafted exploration of love tested by trauma.

Maria's Lovers remains a potent reminder that sometimes the greatest battles are fought not on foreign fields, but within the quiet spaces of the human heart, long after the guns have fallen silent.