There's a certain weight that settles in when you watch Walter Hill's Geronimo: An American Legend (1993). It’s not the explosive thrill of his earlier works like The Warriors or 48 Hrs.; instead, it's the heavy presence of history, of inevitability, captured through Hill’s distinctively masculine, yet here almost elegiac, lens. Finding this tape again, perhaps tucked between flashier action flicks on the rental shelf back in the day, felt like unearthing something significant, something demanding quiet contemplation long after the VCR clicked off. It wasn’t just another Western; it felt like bearing witness.

A Landscape of Loss

From the opening frames, narrated by a young, earnest Matt Damon as the fresh-faced Lt. Britton Davis, the film establishes a somber tone. This isn't a celebration of westward expansion; it's a chronicle of its brutal end game, focusing on the final free days of the Chiricahua Apache and their most feared, most mythologized leader. The vast, beautiful, yet unforgiving landscapes of Utah and Arizona, captured with Hill’s characteristic eye for rugged beauty, serve less as a majestic backdrop and more as a shrinking cage, the last bastion of a way of life being systematically extinguished. The feeling isn't adventure, but a slow, encroaching dread. What does freedom mean when your world is disappearing acre by acre?

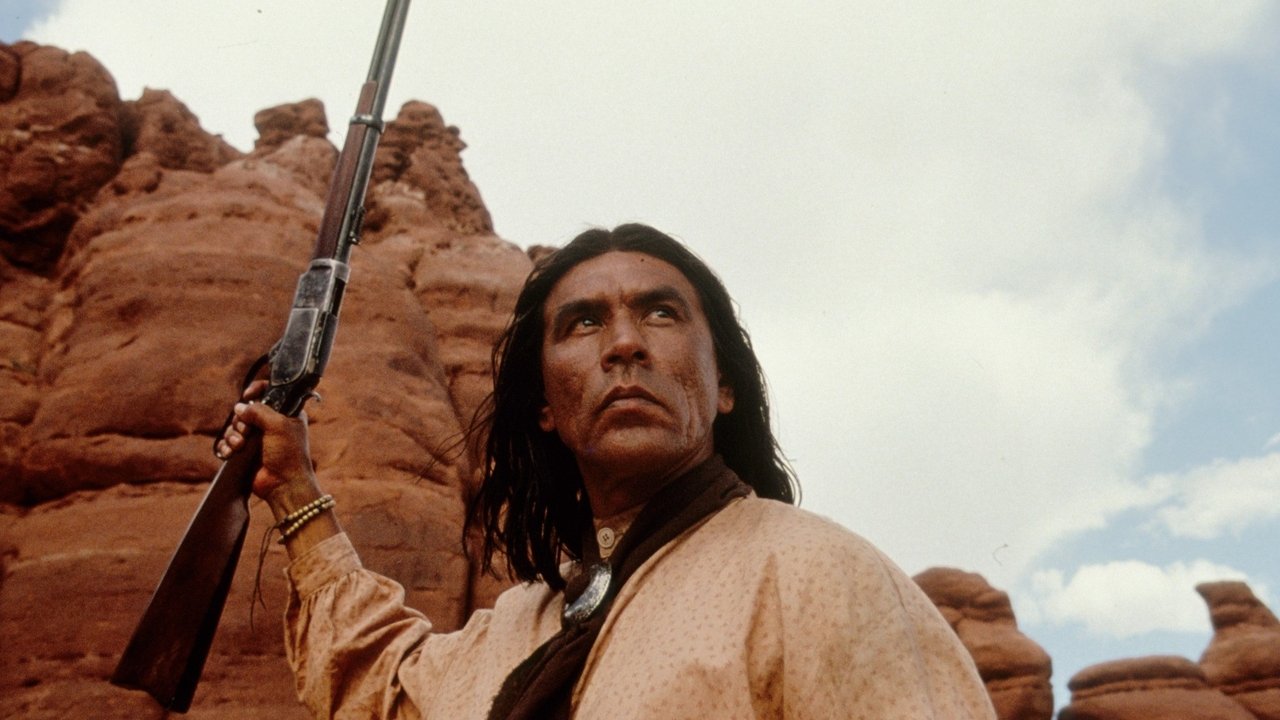

Embodying a Legend

At the heart of it all is Wes Studi as Geronimo. Following his searing performance in The Last of the Mohicans (1992), Studi delivers something truly magnetic here. He embodies Geronimo not just as a fierce warrior, but as a man burdened by loss, driven by visions, and grappling with impossible choices. There's a profound stillness in his portrayal, a gaze that carries the weight of broken treaties and relentless pursuit. It's a performance that resists easy categorization – he’s neither noble savage nor monstrous villain, but a complex human being pushed to the edge. Studi, himself Cherokee, dedicated himself to portraying the Apache leader with dignity, reportedly learning Chiricahua phrases and immersing himself in the culture. It's this dedication that allows the character to transcend the historical figure and become a powerful symbol of resistance against overwhelming force.

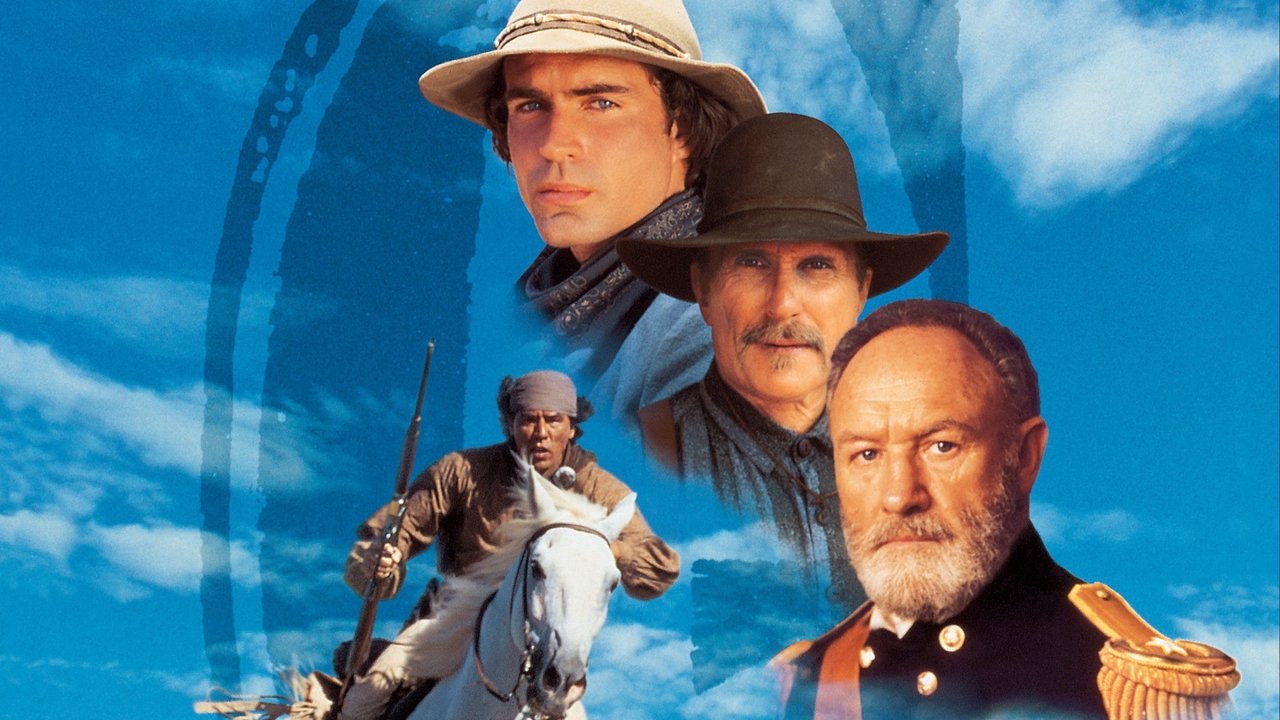

Men Caught in the Machine

Surrounding Studi is a formidable cast representing the forces closing in. Jason Patric plays Lt. Charles Gatewood, the officer tasked with bringing Geronimo in, carrying a weary respect for the man he hunts. Patric conveys the moral ambiguity of his position, caught between duty and a dawning understanding of the injustice unfolding. Then there are the veteran powerhouses: Gene Hackman as Brigadier General George Crook, pragmatic and soldierly, trying to navigate the politics and warfare with a certain weary honor, and Robert Duvall as Al Sieber, the grizzled, cynical chief of scouts, embodying the harsh realities of the frontier. Watching Hackman and Duvall, two titans of American cinema, share scenes crackles with unspoken history – their weary professionalism perfectly mirrors the characters they portray. Their presence lends the film an undeniable gravitas.

Hill, Milius, and the Weight of History

Walter Hill's direction is assured, staging moments of brutal, sudden violence characteristic of his style, but often pulling back to emphasize the human cost. The action feels less like spectacle and more like spasms of desperation. The script, co-written by John Milius (infamous for Apocalypse Now and Conan the Barbarian) and Larry Gross, carries some Milius hallmarks – an interest in warrior codes, the burden of command – but filters them through a more mournful, less triumphant lens than some of his other work. It attempts to weave multiple perspectives, primarily through Davis's narration, offering glimpses into the motivations and mindsets on both sides of the conflict.

Unearthing Retro Insights

Geronimo: An American Legend arrived in 1993, part of a brief resurgence of the Western genre that also included the much flashier Tombstone. Despite its pedigree and a substantial budget for the time (around $35 million – roughly $74 million in today's money!), the film was a commercial disappointment, grossing only about $18.6 million domestically. Perhaps its somber tone and refusal to offer easy heroes or clear victories didn't align with audience expectations for a Western epic. It's a shame, as the film boasts incredible production value, authentic costuming, and features Ry Cooder's haunting, atmospheric score, which perfectly complements the dusty, sun-baked visuals and the pervasive sense of melancholy. For fans spotting familiar faces, seeing Matt Damon in such a significant early role, essentially guiding the narrative, is a fascinating piece of trivia. This film feels like a necessary counterpoint to more romanticized visions of the West; it dares to show the ugliness alongside the beauty.

The Lingering Question

The film doesn't shy away from the brutality committed by both sides, but its core focus remains on the tragic trajectory of Geronimo and his people. It leaves you contemplating the nature of history, how legends are forged in bloodshed and misunderstanding, and the promises broken in the name of progress. It’s a film that doesn't offer easy answers but instead asks us to sit with the discomfort, to consider the human cost of conflict and conquest. Doesn't the struggle for cultural survival, the resistance against erasure, still echo in challenges faced today?

Rating: 8/10

Geronimo: An American Legend earns its 8/10 for its powerful central performance by Wes Studi, the stunning cinematography capturing the harsh beauty of the landscape, the weighty contributions of Hackman and Duvall, and its admirable, if somber, attempt to grapple with a complex and painful chapter of American history. While its narrative structure, relying heavily on narration, might feel a bit fragmented to some, and its pacing is deliberately measured rather than action-packed, the film’s atmosphere and Studi’s portrayal are unforgettable.

It remains a potent, often overlooked Western from the VHS era – a film less concerned with shootouts and more with the slow, grinding erosion of a people and the defiant spirit of their leader. It’s a heavy watch, but a necessary one.