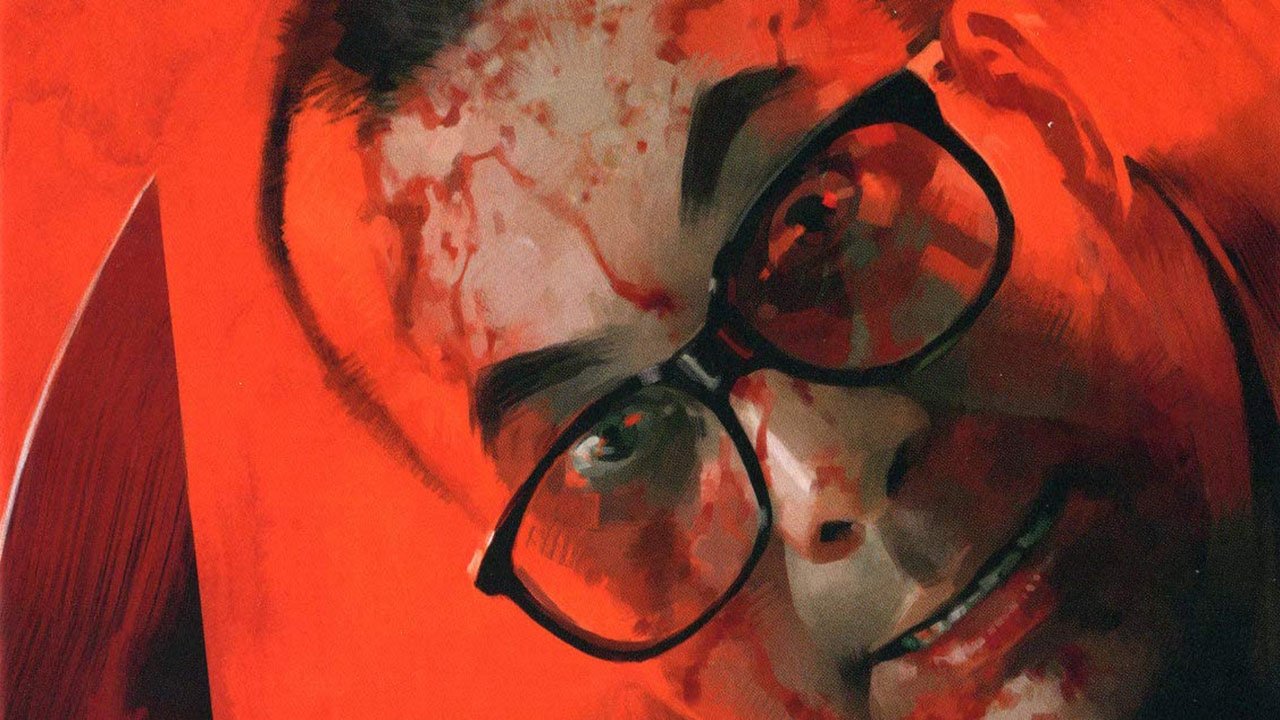

Some video tapes felt heavier than others on the rental store shelf, didn't they? They carried a weight beyond the plastic casing and spools of magnetic tape – a whispered reputation, a rumour of boundary-pushing content. Few carried that weight quite like The Untold Story (1993), a film that arrived from Hong Kong under the notorious Category III label, promising something far removed from the usual kung fu flicks or glossy melodramas. And promise, it horrifyingly delivered.

This isn't a film you ease into; it plunges you headfirst into a grimy, sweltering Macau where the stench of desperation seems to cling to the very celluloid. We're initially grounded by the familiar presence of Danny Lee (often the stalwart cop figure in Hong Kong cinema, and producer here), leading a police investigation into human remains washing ashore. But the procedural aspect quickly becomes a framing device for something far more visceral and disturbing: the story of Wong Chi Hang, the new owner of the Eight Immortals Restaurant.

A Descent into Mundane Evil

Enter Anthony Wong Chau-Sang. Forget movie monsters or supernatural threats. Wong's portrayal of the restaurant owner is a masterclass in mundane monstrosity. He’s not a cackling villain; he's sweaty, irritable, quick to anger, capable of sudden, shocking violence that erupts from petty grievances. His performance is utterly magnetic and deeply repulsive, a transformation so complete it famously, and controversially, earned him the Hong Kong Film Award for Best Actor. Rumours persisted about Wong's intense method approach, apparently staying in character and deeply unsettling cast and crew – looking at the final product, it’s disturbingly easy to believe. He embodies a terrifyingly ordinary sort of evil, the kind that could be lurking behind any unassuming storefront.

The film, directed by Herman Yau (who would later bring us the Ip Man origin story, showing incredible range), slowly peels back the layers of Wong Chi Hang's past and his connection to the restaurant's previous owners. What unfolds is based, chillingly, on the real-life 1985 'Eight Immortals Restaurant murders' in Macau, where a gambler named Huang Zhiheng murdered a family of ten and allegedly served their remains to unwitting customers. The Untold Story doesn't flinch from depicting the alleged events with a raw, unflinching brutality that was genuinely shocking, even by the often-extreme standards of Category III cinema.

The Texture of Dread

What makes The Untold Story burrow under your skin isn't just the graphic violence – though there's plenty of that, rendered with a grim practicality that feels sickeningly real. It’s the atmosphere Yau cultivates. The cramped restaurant kitchen, the sticky summer heat, the gaudy backdrop of Macau's gambling dens – it all combines to create an oppressive sense of unease. There’s little stylistic flourish; the horror feels grounded, almost documentary-like in its ugliness. The film juxtaposes scenes of grotesque violence with moments of banal everyday life – Wong playing mahjong, complaining about business – making the eruptions of savagery feel even more jarring and unpredictable.

I distinctly remember the buzz around this film when copies started circulating on VHS, often traded among fans of extreme Asian cinema. It felt illicit, something you watched late at night with the volume low, half-expecting a knock at the door. The grainy NTSC transfer somehow enhanced the griminess, the imperfections of the medium mirroring the moral decay on screen. Does that feeling still resonate? Watching it today, the shock value might be tempered for viewers desensitized by decades of screen violence, but the sheer nastiness and Anthony Wong's unforgettable performance retain their power. The film's production wasn't without its own dark legends; whispers about the psychological toll on Wong and the sheer difficulty of filming such harrowing scenes add another layer to its grim legacy. Made for a modest sum, its controversial nature and shocking content turned it into a notorious success story within its niche.

Beyond the Gore

While often remembered purely for its graphic content, The Untold Story also functions as a bleak social commentary. It touches on police corruption, the desperation fueled by gambling addiction, and the simmering frustrations of lower-class life. Danny Lee's police team aren't exactly shining examples of justice; their methods, particularly in the interrogation scenes, are brutal in their own right, blurring the lines between law enforcement and sadism. It presents a world where violence begets violence, and humanity feels like a fragile commodity. Emily Kwan also deserves mention for her harrowing portrayal of one of the victims, bringing a tragic human element amidst the brutality.

This film isn't "fun" in any conventional sense. It’s a cinematic ordeal, a confrontational piece of work designed to provoke and disturb. It represents a specific, wild period in Hong Kong filmmaking where censorship was loosening, and directors like Herman Yau pushed boundaries with raw, often exploitative, energy.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: The Untold Story is undeniably effective at achieving its grim goals. Anthony Wong's powerhouse performance is legendary for a reason, and Herman Yau crafts an atmosphere of palpable dread. Its basis in true crime adds a chilling layer, and its unflinching depiction of violence makes it a landmark (albeit notorious) example of Category III cinema. However, its extreme, often stomach-churning content makes it a difficult watch, bordering on exploitative, which prevents a higher score. It’s technically proficient and impactful, but its appeal is inherently limited to those who can stomach its brutality.

Final Thought: More than just a gore-fest, The Untold Story remains a potent and deeply unsettling piece of extreme cinema, anchored by one of the most terrifyingly believable monster portrayals ever committed to film. It’s a tape you might only watch once, but its grim flavour lingers long after the screen goes dark.