## The Unseen Walls of Desire

There's a certain kind of quiet intensity that cinema, particularly from auteurs operating outside the mainstream, can achieve like no other medium. It’s a stillness that vibrates with unspoken tension, where glances hold volumes and the spaces between words feel vast and significant. Chantal Akerman's La Captive (The Captive), released right at the turn of the millennium in 2000, possesses this quality in abundance. It’s a film that feels less like a narrative unfolding and more like an observation chamber, meticulously documenting the suffocating dynamics of obsessive love, demanding a patience and attention that feels almost nostalgic in itself – a throwback to a time before endless scrolling, when you might commit to a challenging film discovered on a sparsely decorated VHS cover in the 'World Cinema' aisle.

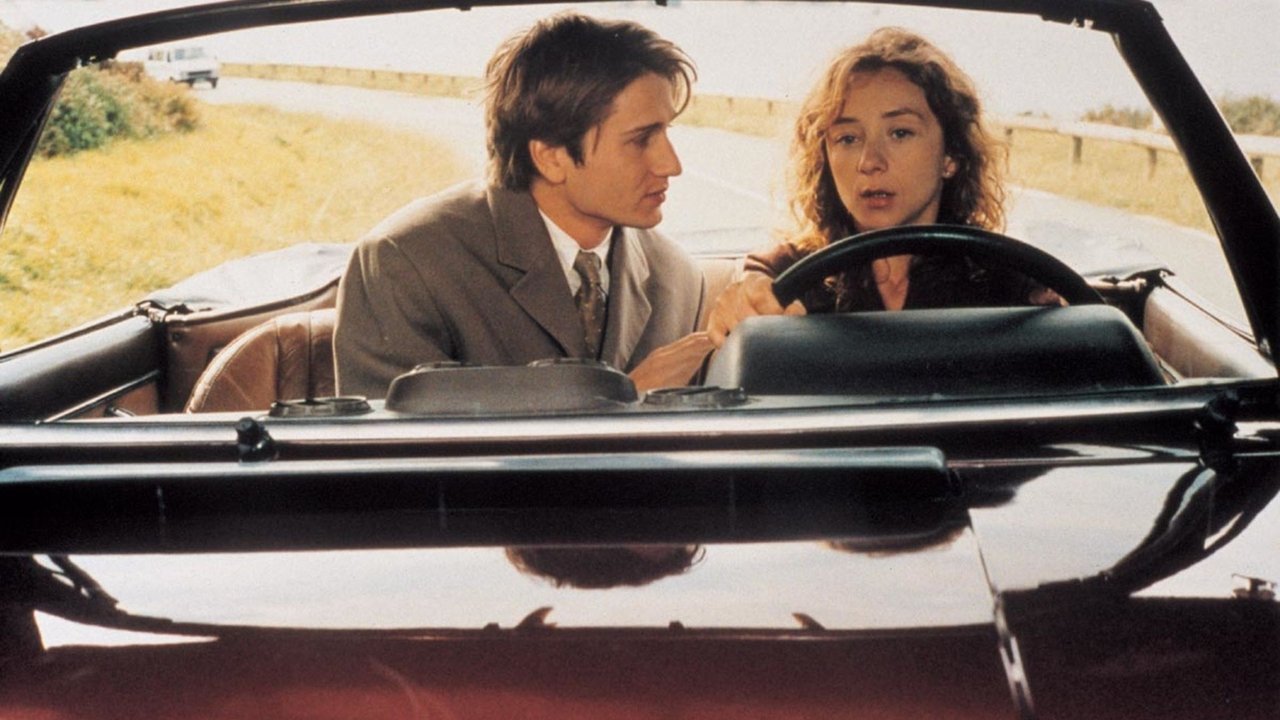

Loosely inspired by the fifth volume of Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time (La Prisonnière), the film centres on Simon (Stanislas Merhar) and his consuming fixation on Ariane (Sylvie Testud). They live together in his opulent Parisian apartment, a gilded cage where Simon spends his days and nights watching Ariane, photographing her, following her, listening at doors, desperate to possess not just her presence, but the entirety of her inner life, particularly her suspected relationships with women, notably her friend Andrée (Olivia Bonamy). It’s a setup ripe for melodrama, yet Akerman, ever the master of restraint, steers sharply away from histrionics.

A Study in Seeing, Not Knowing

What distinguishes The Captive is Akerman's deliberate, almost unnervingly calm directorial hand. Known for her minimalist and often feminist-informed works like the landmark Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Akerman employs long takes, static shots, and a pervasive sense of distance. We observe Simon observing Ariane. We watch her sleeping, bathing, moving through the apartment, often framed through doorways or captured in mirrors. The camera rarely seeks to penetrate Ariane's thoughts; instead, it mirrors Simon's own futile quest. He sees everything, yet understands nothing. This visual strategy is central to the film's power. The opulent apartment, rather than feeling luxurious, becomes claustrophobic, its beauty rendered sterile by the obsessive gaze that patrols it. The cinematography often bathes scenes in a cool, detached light, emphasizing the emotional chilliness underpinning the relationship.

Performances of Evasion and Obsession

The performances are perfectly attuned to Akerman's vision. Stanislas Merhar, with his brooding intensity and haunted eyes, embodies Simon's consuming jealousy not as explosive rage, but as a persistent, soul-eroding ache. He projects a vulnerability that almost makes his possessiveness understandable, yet never excusable. His actions – the constant surveillance, the interrogations disguised as casual questions – are chilling precisely because they feel so psychologically plausible within the warped reality of his obsession.

But it's Sylvie Testud as Ariane who is the film's enigmatic heart. Her performance is a masterclass in ambiguity. Is she a victim, knowingly playing along, or genuinely unaware of the depths of Simon's suspicion? Testud keeps Ariane perpetually just out of reach, her expressions fleeting, her motives opaque. She allows Simon (and the audience) glimpses of warmth or connection, only to retreat behind a veil of polite inscrutability. It's a performance that forces us to confront the fundamental unknowability of another person, even one we live with intimately. Olivia Bonamy also makes a strong impression as Andrée, representing the specific focus of Simon's anxieties and the external world Ariane might inhabit away from his gaze.

The Weight of Unanswered Questions

The Captive isn’t a film that offers easy answers or resolutions. It deliberately frustrates conventional narrative expectations. Akerman is less interested in what Ariane is hiding (if anything) and more interested in the nature of Simon's need to know, the destructive impulse to control and possess another human being completely. It raises unsettling questions: Can love exist alongside total possession? Is jealousy an inherent part of intense passion, or its poison? The film offers no lectures, only a meticulously crafted atmosphere where these questions hang heavy in the air. It’s a challenging watch, certainly. Its pacing is measured, demanding immersion. I remember finding a copy years ago, perhaps on an early DVD release alongside its VHS counterpart, and being struck by how different it felt from almost everything else available – a quiet film demanding loud attention.

Its 2000 release places it just outside the strict 80s/90s timeframe of "VHS Heaven," yet its aesthetic, its challenging arthouse sensibility, and its likely discovery by many on home video formats of that transitional era make it feel relevant to our shared cinematic explorations. It's a potent reminder of a kind of filmmaking that prioritizes mood, psychological depth, and visual storytelling over plot mechanics.

Rating: 8/10

The Captive earns this rating for its masterful direction, hypnotic atmosphere, and compellingly nuanced performances. Akerman crafts a haunting and indelible portrait of obsessive love that lingers precisely because of its ambiguities. It's not a comfortable film, nor an easily digestible one, but its artistic control and thematic depth are undeniable. It might not be a Friday night popcorn flick, but for viewers willing to submit to its deliberate pace and unsettling gaze, it offers profound reflections on the complexities of desire and the inherent solitude of the human condition.

What remains, long after the credits roll, is the echo of Simon's watching eyes and the unsettling realization that sometimes, the closer we try to get, the less we truly see.