Before the operatic grandeur of Apocalypse Now or the raw trauma of The Deer Hunter redefined the Vietnam War film for many, there was a quieter, dustier, and perhaps even more cynical tremor that registered the early, confused stages of American involvement. I'm talking about Ted Post's 1978 picture, Go Tell the Spartans. This wasn't a film that exploded onto screens; it felt more like it seeped into consciousness, particularly for those of us who discovered its potent truths tucked away on a video store shelf, years after its low-key theatrical run. It’s a film that doesn't shout its horrors, but lets them settle on you like the ever-present Vietnamese dust.

The Bleak Dawn of Intervention

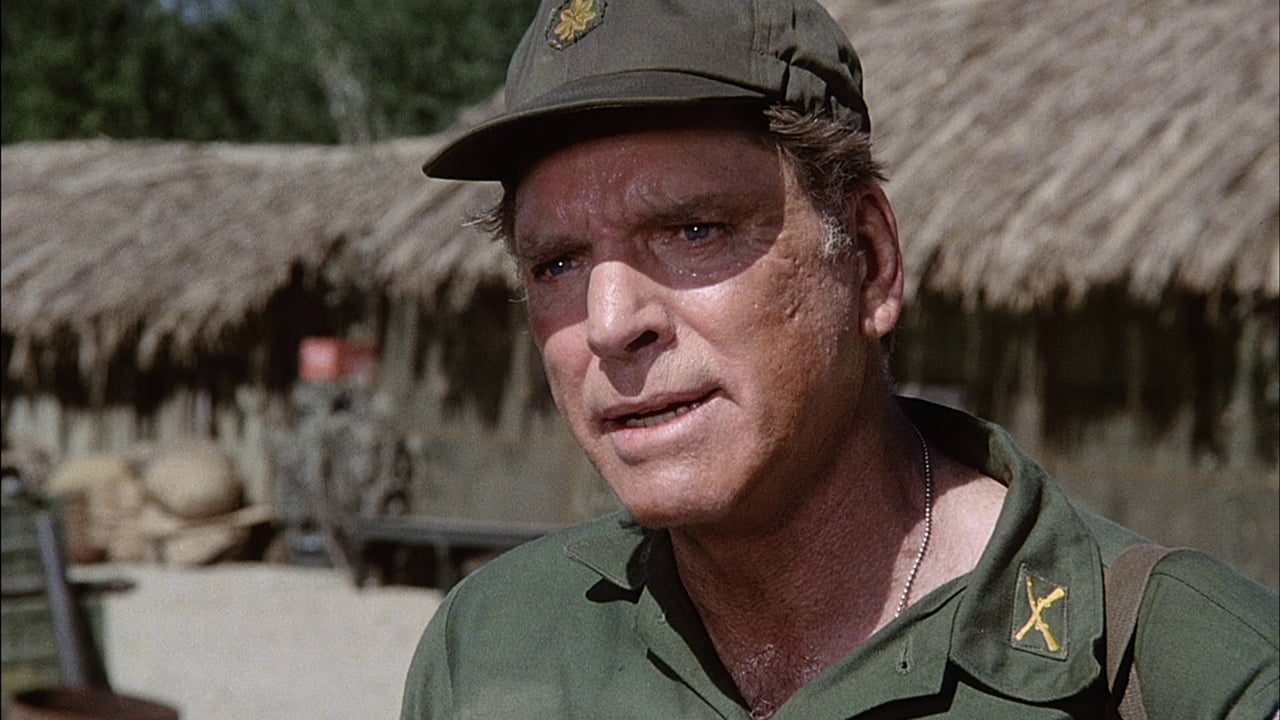

Set in the seemingly distant past of 1964, Go Tell the Spartans avoids the full-blown chaos that would later dominate narratives of the conflict. Instead, it focuses on a small contingent of American military advisors tasked with garrisoning a deserted, strategically questionable outpost called Muc Wa. Leading this thankless charge is Major Asa Barker, portrayed with magnificent weariness by the legendary Burt Lancaster. Barker is no gung-ho warrior; he’s a veteran of two previous wars, acutely aware of the political gamesmanship and the likely futility of their mission, yet bound by a soldier's duty. The plot unfolds not as a series of heroic battles, but as a slow descent into logistical nightmares, cultural misunderstandings, and the dawning realization that they are pawns in a game whose rules haven't even been written yet.

Lancaster's Heavy Mantle

At the absolute core of the film is Burt Lancaster. In one of his finest later performances, he embodies the disillusionment of a professional soldier grappling with the nonsensical realities of this new kind of conflict. His Barker is gruff, pragmatic, occasionally even harsh, but beneath the surface lies a deep-seated empathy and a profound sense of foreboding. There's a weight in his eyes, a slump in his shoulders that speaks volumes about the burden he carries. It’s a performance devoid of vanity, built on subtle gestures and world-weary line deliveries. It’s said Lancaster believed so strongly in the script, based on Daniel Ford's novel "Incident at Muc Wa," that he agreed to work for union scale just to get the film made. That commitment radiates from the screen; he is Barker, the old soldier watching the familiar, tragic patterns repeat themselves.

Faces in the Dust

Surrounding Lancaster is a capable cast representing the various archetypes thrust into this confusing crucible. A young Craig Wasson (later of Brian De Palma's Body Double) plays Corporal Courcey, the idealistic draftee whose initial eagerness slowly erodes under the harsh sun and harsher realities. His journey serves as the audience's entry point into the madness. We also see familiar faces like Jonathan Goldsmith, years before becoming "The Most Interesting Man in the World," as a seasoned but weary Sergeant. Each character, from the cynical medic to the career-obsessed Captain, feels grounded, contributing to the film's unvarnished portrayal of men caught in the gears of an ill-defined war machine. There are no super-soldiers here, just flawed humans trying to survive.

A Different Kind of War Film

What truly sets Go Tell the Spartans apart, especially considering its 1978 release date, is its utter lack of romanticism. Director Ted Post, perhaps better known for genre work like Magnum Force or Beneath the Planet of the Apes, adopts a stark, almost documentary-like style. The action, when it comes, is messy, confusing, and brutal, devoid of heroic framing. The film is more interested in the absurdity of command decisions, the communication breakdowns, and the quiet dread that permeates the camp. The title itself, a direct reference to the epitaph for the Spartans who fell defending the pass at Thermopylae ("Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here, obedient to their laws, we lie"), carries a profound and tragic irony. Are these men heroes defending a noble cause, or sacrifices offered up to flawed strategies and political expediency? The film strongly suggests the latter.

Retro Grit and Lasting Echoes

Filmed on a tight budget (reportedly around $1.5 million) primarily in Valencia, California, the production itself mirrors the make-do reality depicted on screen. The locations convincingly evoke the dusty, sun-baked atmosphere of Vietnam, and the lack of expensive pyrotechnics forces the focus onto the characters and their psychological states. This wasn't a box office smash; it found its audience slowly, through word-of-mouth and, crucially, through home video. I remember encountering the distinctive VHS box art, Lancaster's tired face promising something different from the usual war movie fare. Watching it felt like unearthing a hidden truth, a prescient warning issued before the national consciousness fully grappled with the war's complexities. Its initial lukewarm reception makes its later critical reappraisal and cult following all the more satisfying for those of us who recognized its quiet power early on.

The film doesn't offer easy answers or cathartic victories. It presents the Vietnam conflict not as a clear struggle between good and evil, but as a murky, morally ambiguous quagmire where good intentions pave roads to disaster. Doesn't this portrayal of confusion and unintended consequences still resonate with conflicts happening decades later?

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's powerful, understated realism, Burt Lancaster's towering central performance, and its unflinching, prescient critique of the early Vietnam conflict. It earns its high marks for daring to be unglamorous, cynical, and deeply human in its portrayal of war, avoiding the jingoism or simplistic narratives that sometimes plagued the genre. Its low-budget grit only enhances its authenticity. Go Tell the Spartans remains a vital piece of war cinema, a film whose quiet truths about the cost of ill-conceived adventures echo long after the tape stops rolling. It leaves you not with a sense of triumph, but with a lingering question about the price of obedience.