It's a quiet weight that settles in the room when certain films end, isn't it? Not the silence of boredom, but the heavy quiet of contemplation. Playing for Time, the landmark 1980 television film, leaves precisely that kind of stillness. Originally broadcast on CBS, it felt less like typical evening entertainment and more like an event – something demanding attention, something that lingered long after the flickering cathode ray tube went dark. Watching it again now, decades removed from its initial impact, that sense of gravity hasn't diminished one bit. This isn't a film you revisit for escapism; it's one you return to out of a sense of necessity, a need to bear witness.

The Unflinching Mirror

Based on the harrowing autobiographical account by Fania Fénelon, a French Jewish singer and pianist, the film plunges us into the unimaginable reality of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp during World War II. Adapted for the screen with stark power by the legendary playwright Arthur Miller (Death of a Salesman, The Crucible), the narrative centers on Fénelon's induction into the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz. This group of prisoners, possessing musical talent, were afforded grim privileges – slightly better conditions, exemption from the gas chambers – in exchange for performing for their Nazi captors, including the infamous Josef Mengele. The premise itself is a study in profound moral complexity: Does art offer solace or merely serve as a grotesque decoration for barbarity? Can survival justify collaboration, even on these terms? Miller’s script doesn't offer easy answers, instead laying bare the brutal choices and the erosion of spirit under duress.

A Controversial, Captivating Center

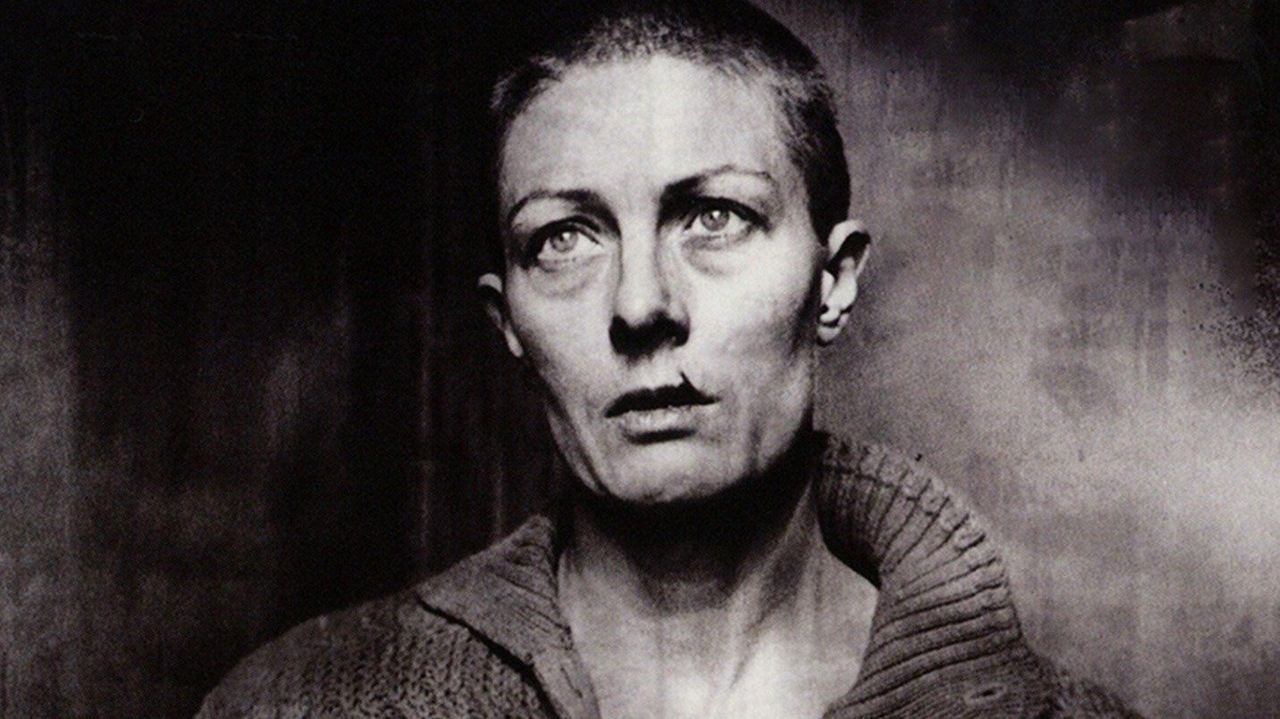

At the heart of the film is Vanessa Redgrave's portrayal of Fania Fénelon. It’s a performance etched in memory, not just for its raw intensity but also for the considerable controversy surrounding her casting. Redgrave's outspoken pro-Palestinian Liberation Organization views at the time led to protests and security concerns during production and broadcast. Fénelon herself publicly distanced herself from Redgrave's politics and aspects of the portrayal. Setting aside the external storm, Redgrave's work on screen is undeniable. Having famously shaved her head for the role, she embodies Fania with a fierce, almost defiant vulnerability. We see the flicker of the sophisticated Parisian performer grappling with the dehumanizing horror, the moments of connection with fellow prisoners, and the quiet, soul-crushing compromises made simply to draw the next breath. It’s a performance that feels stripped bare, confronting the audience with the physical and psychological toll of the camps. Does it perfectly capture Fénelon's own account? Perhaps not entirely, given the author's own critiques, but as a dramatic interpretation, its power is immense.

The Weight of Command

Equally compelling is Jane Alexander (Kramer vs. Kramer, All the President's Men) as Alma Rosé, the orchestra's formidable conductor. Rosé, herself a renowned violinist and niece of composer Gustav Mahler, wields her limited authority with a stern, almost ruthless pragmatism. Alexander portrays her not as a villain, but as another soul navigating an impossible situation, convinced that discipline and musical perfection are the only shields against annihilation. The dynamic between Alexander's tightly wound Rosé and Redgrave's more openly expressive Fénelon forms the film's emotional core – a clash of wills, strategies for survival, and tragically shared fates. Alexander deservedly won an Emmy for her supporting role, bringing a chilling dignity and complexity to a figure who could easily have become a caricature.

Art in the Abyss

What does it mean to play Schubert while smoke rises from the crematoria? Playing for Time forces this question relentlessly. The music isn't presented as a simple symbol of hope; it's complicated, tainted. It’s a tool used by the SS for their amusement, a means to soothe them before they commit further atrocities, and yet, for the women playing, it’s also a fragile lifeline, a connection to a world of beauty and order that seems galaxies away. The film, initially under the direction of Daniel Mann before he was replaced by Joseph Sargent (who helmed gritty classics like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three [1974] and received the Emmy for directing this), captures this dissonance effectively. Sargent’s direction maintains a stark, almost documentary-like feel, avoiding overt sentimentality, allowing the inherent horror and the nuances of the performances to carry the weight. Filmed not in Europe, but at Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, the production nonetheless creates a convincing atmosphere of dread and confinement.

Behind the Somber Lens

Remembering Playing for Time isn't just about the film itself, but its context. This was event television, a major network committing significant resources (and facing considerable flak) to tell a profoundly difficult story. It swept the Emmys, winning not just for Redgrave, Alexander, Sargent, and Arthur Miller, but also for Outstanding Drama Special. It felt important then, a stark contrast to much of the programming surrounding it. Fénelon’s own memoir caused debate, and the film added layers to that discussion, particularly regarding historical accuracy versus dramatic interpretation. Miller's script, while powerful, takes liberties, as adaptations often must. Knowing that Fénelon felt her experience was somewhat misrepresented, particularly regarding the level of camaraderie and resistance, adds another layer to consider when watching.

Enduring Echoes

Does Playing for Time still hold up? Absolutely. Its unflinching gaze, anchored by towering performances from Redgrave and Alexander, remains deeply affecting. It stands as a vital piece of Holocaust cinema, offering a unique perspective on the complexities of survival within the camps through the specific lens of the women's orchestra. It doesn’t offer catharsis or easy resolution; instead, it leaves you with the haunting questions it raises about humanity, art, and the impossible choices made in the shadow of death. It’s a film that reminds us why certain stories, no matter how painful, must continue to be told and wrestled with.

Rating: 9/10

The score reflects the film's sheer power, its historical significance as a television event tackling a monumental subject, and the unforgettable, Emmy-winning performances by Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Alexander. Arthur Miller's adaptation is stark and intelligent, and Joseph Sargent's direction is appropriately sober. While the controversy surrounding Redgrave and Fénelon's own criticisms slightly temper a perfect score, they don't diminish the film's raw impact and importance.

Playing for Time isn't entertainment; it's testimony, rendered through the powerful medium of drama, demanding remembrance long after the music has faded.