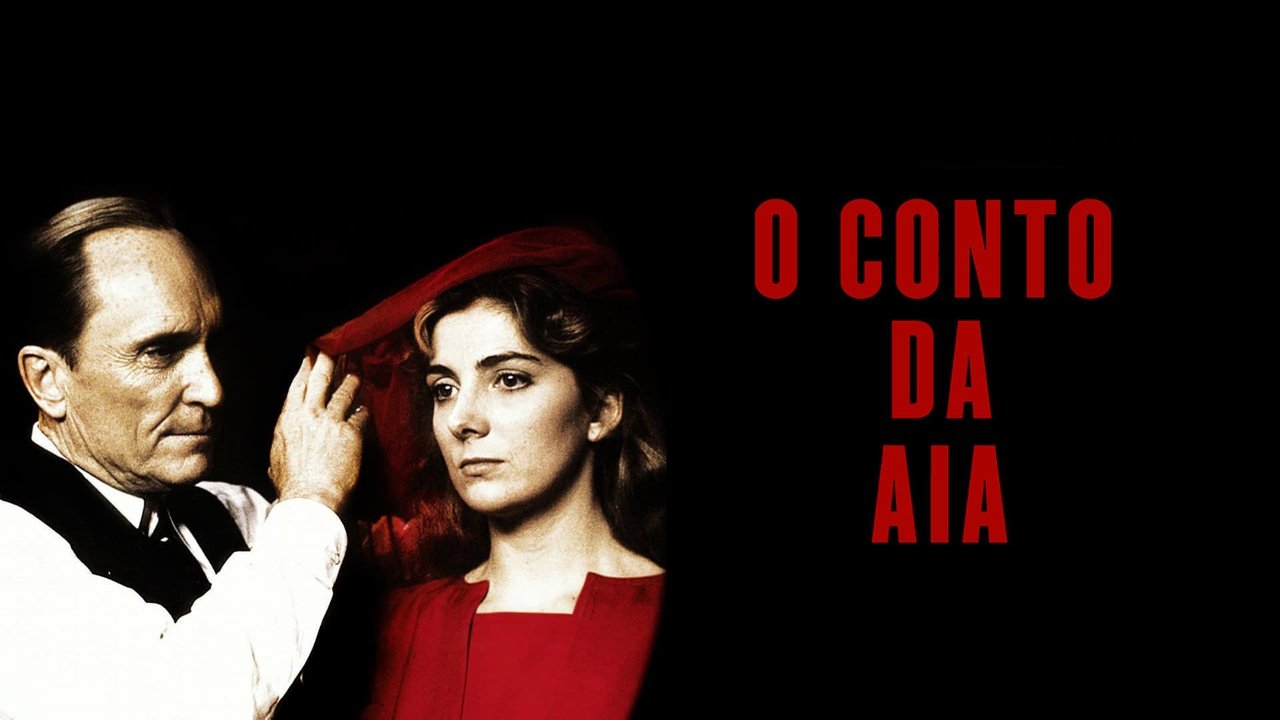

Amidst the explosion of neon-drenched action flicks and high-concept comedies that defined the video store aisles of 1990, some tapes carried a different kind of weight. Tucked perhaps between a Schwarzenegger epic and a John Hughes teen classic, you might have found a cover art far more somber, hinting at a reality much closer, and far more chilling, than any space opera. Volker Schlöndorff's adaptation of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale was one such film – a stark, often uncomfortable vision that, even viewed through the nostalgic haze of CRT static, retains a disquieting power.

It wasn’t an easy watch then, and it certainly isn't now. The film plunges us headfirst into the chillingly plausible dystopia of Gilead, a near-future America transformed into a theocratic state where environmental collapse and rampant infertility have led to a terrifying social order. Women are brutally subjugated, stripped of their names and identities, and fertile women, the Handmaids, are reduced to reproductive vessels for the ruling elite. It’s a premise that chills to the bone, forcing us to confront uncomfortable questions about power, faith, gender, and the fragility of freedom. Doesn't the echo of such concerns feel eerily persistent today?

A World Drained of Colour, Save One

Schlöndorff, the acclaimed German director behind the Palme d'Or and Oscar-winning The Tin Drum (1979), brings a certain European arthouse sensibility to this American nightmare. Working with cinematographer Igor Luther, he crafts a world visually defined by oppressive order and muted tones – sterile interiors, imposing architecture, a landscape seemingly leached of hope. Against this desaturated backdrop, the blood-red habits of the Handmaids stand out with shocking intensity, a constant, visceral reminder of their function and their captivity. This deliberate visual language is one of the film's strongest assets, creating an atmosphere thick with dread and unspoken menace. The production design, including those now-iconic costumes by Colleen Atwood (who would go on to win multiple Oscars for films like Chicago and Alice in Wonderland), wasn't just aesthetic; it was integral to communicating the rigid hierarchy and dehumanization central to Gilead's ideology. Filming primarily in Durham, North Carolina, using locations like Duke University's gothic architecture, lent an unsettling familiarity to the oppressive regime, grounding the fantastical in the recognizable.

Richardson's Quiet Defiance

At the heart of this bleak world is Offred, portrayed by the luminous Natasha Richardson. Her task is immense: embodying a character largely defined in the novel by a rich, often defiant, internal monologue. The adaptation, famously scripted by Nobel laureate Harold Pinter, streamlines much of this interiority, relying instead on Richardson’s performance and sporadic voiceover to convey Offred’s fear, suppressed memories, and flickering embers of resistance. Richardson is captivating, her face a canvas of subtle emotions – vulnerability, weary resignation, flashes of the woman she once was, and quiet, dangerous moments of defiance. She carries the film's emotional weight, making Offred's plight deeply felt. It’s a performance that relies on stillness and observation, drawing us into her terrifying reality. Watching her navigate the treacherous dynamics of the Commander's household is a masterclass in nuanced acting.

A High-Caliber Cast in a Chilling Ensemble

Surrounding Richardson is a formidable cast. Faye Dunaway, fresh off a career resurgence, is icily perfect as Serena Joy, the Commander's barren wife, radiating brittle privilege and simmering resentment. Her scenes with Richardson crackle with tension, a complex dynamic of shared oppression and hierarchical cruelty. Robert Duvall brings a chilling banality to the Commander; he isn't a mustache-twirling villain, but a man utterly convinced of the righteousness of this horrific system, making him perhaps even more terrifying. His attempts at connection with Offred, particularly the illicit Scrabble games, are deeply unsettling. And Aidan Quinn as Nick, the Guardian who represents a potential spark of connection and danger for Offred, offers a necessary counterpoint, though the film perhaps simplifies their relationship compared to the novel's ambiguities.

Retro Fun Facts: Pinter, Politics, and Production Hurdles

The journey from page to screen wasn't smooth. Harold Pinter's initial script reportedly diverged significantly from Atwood's novel, leading to rewrites (some reportedly by Atwood herself, though uncredited) to bring it closer to the source material. Pinter, known for his sparse dialogue and palpable menace, was apparently unhappy with the final result and distanced himself from it, though his name remains prominent in the credits. This behind-the-scenes tension perhaps reflects the inherent difficulty in translating Atwood’s dense, internal narrative into a visual medium. The film also faced censorship battles, initially threatened with an X rating before being trimmed for its R, likely softening some of the novel's more brutal aspects concerning sexual violence. With a budget of around $13 million, it performed modestly at the US box office, grossing just under $5 million – perhaps its stark message and challenging themes were a harder sell in 1990 compared to the more explicit political anxieties that fueled the success of the later television series. Finding concrete details on specific stunt work or technical hurdles is difficult, but the overall production achieved a chillingly believable dystopia on its budget.

Lost in Translation?

While visually striking and powerfully acted, the film does struggle with the loss of Offred's pervasive internal voice from the novel. The voiceover feels occasionally functional rather than deeply revelatory, and some of the novel's complex political and social commentary is inevitably streamlined. It simplifies certain relationships and plot points, opting for a more conventional narrative structure, particularly towards the end. For those who know the book intimately, these omissions might feel significant. Yet, judged on its own terms as a piece of 90s cinema, it stands as a serious, often unnerving attempt to grapple with profound themes. It dared to present a mainstream audience with a deeply unsettling vision, planting seeds of unease that resonate differently, but perhaps no less powerfully, than the more expansive modern series.

Final Reflection

Watching The Handmaid's Tale today, especially on a format like VHS that feels like a relic of a past era itself, is a strange experience. It’s a film that feels both dated in its specific 90s cinematic language and chillingly relevant in its core concerns. It may not capture the full depth and nuance of Atwood's masterpiece, but it offers a potent, atmospheric, and superbly acted distillation of its terrifying vision. Richardson's central performance remains unforgettable, a beacon of humanity in a world designed to extinguish it.

Rating: 7/10

The score reflects a film that is commendably ambitious, visually potent, and anchored by outstanding performances, particularly from Richardson and Dunaway. It successfully creates a chilling atmosphere and tackles difficult themes with seriousness. However, it's held back slightly by the inevitable compromises of adapting such a complex, internal novel and a script that streamlines some of the source material's deeper ambiguities and political nuances.

Final Thought: A sobering reminder from the VHS vaults that the anxieties explored in Gilead – control, complicity, the erosion of rights – weren't just speculative fiction then, and tragically, feel anything but distant now. What lingers most is the quiet horror, carried in Natasha Richardson's haunting gaze.