Some films gently unfold, not with grand pronouncements or earth-shattering events, but with the quiet rhythm of everyday life, gradually revealing profound truths. Studio Ghibli's Only Yesterday (1991) is precisely such a film – a delicate watercolour painting of memory and self-discovery that feels miles away from the fantastical realms often associated with the famed animation house, yet carries its own distinct, resonant magic. Watching it feels less like consuming entertainment and more like participating in a quiet, contemplative conversation about the paths we take and the echoes of childhood that shape our adult selves.

It's a film many of us in the West likely missed during its original Japanese release, perhaps discovering it later, tucked away on a shelf or recommended by a fellow Ghibli devotee. Unlike the more immediately accessible adventures of My Neighbor Totoro (1988) or Kiki's Delivery Service (1989), Only Yesterday didn't grace typical American video store shelves in the early 90s. Its eventual wider release revealed a work of surprising maturity and nuance, a gentle current pulling us back not just to the protagonist's past, but perhaps, inevitably, to our own.

A Journey Between Two Times

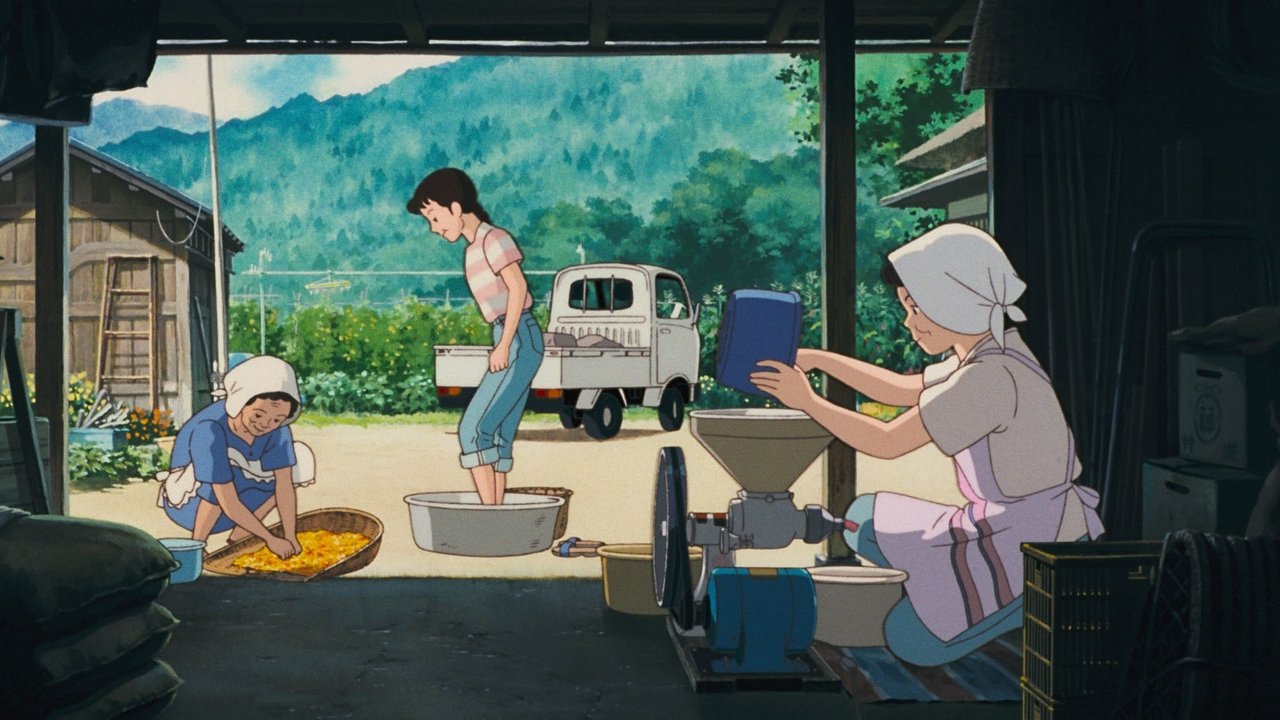

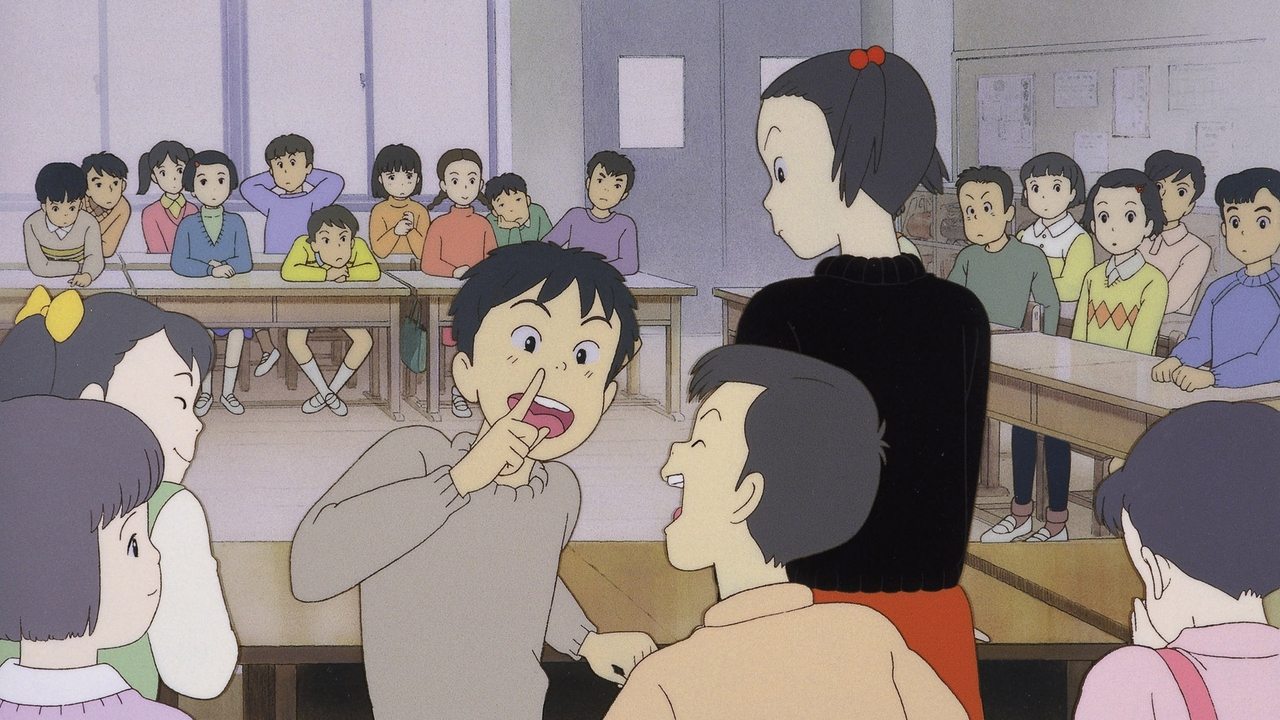

The premise is deceptively simple: Taeko Okajima (Miki Imai), a single 27-year-old woman living and working in Tokyo, decides to escape the city grind and spend time working on a safflower farm in the rural Yamagata Prefecture. The train journey becomes a conduit, not just across physical distance, but through time itself. Memories of her 10-year-old self (Youko Honna) in 1966 begin to surface – vivid, awkward, sometimes embarrassing fragments of fifth grade. Cutting her first pineapple, navigating playground politics, the confusing bloom of puberty, the subtle pressures of family expectations – these moments aren't dramatic plot points but rather the essential texture of growing up.

What makes Only Yesterday so captivating is how director Isao Takahata, the visionary Ghibli co-founder also behind the heartbreaking Grave of the Fireflies (1988), masterfully interweaves these two timelines. The past isn't just recalled; it actively informs and complicates Taeko's present. Her childhood anxieties and unresolved questions subtly mirror her uncertainties as an adult navigating societal expectations and her own quiet dissatisfaction. Is her comfortable city life truly fulfilling? Why do these specific memories resurface now?

Animation as Emotion

Takahata employs a brilliant visual strategy to distinguish the timelines, a choice that speaks volumes about the nature of memory itself. The 1982 present-day scenes are rendered with remarkable detail and realism, particularly in the nuanced facial expressions and body language of the characters. You see the weight of contemplation in adult Taeko's eyes, the easy warmth of Toshio (Toshiro Yanagiba), the young farmer who gently challenges her perspective. Reportedly, Takahata experimented with capturing facial movements of the actors during pre-recording sessions to enhance this naturalism, a pioneering approach for anime at the time.

Conversely, the 1966 flashbacks possess a softer, more impressionistic quality. Backgrounds sometimes fade into watercolour washes or pure white space, suggesting the selective, often emotionally charged focus of memory. Character designs are simpler, capturing the essence of childhood perception. This visual distinction isn't just stylistic flair; it is the film's theme, visually articulating how the sharp details of the present are built upon the sometimes hazy, emotionally potent foundations of the past. The meticulous research into safflower farming, involving trips by the animation team to ensure accuracy, further grounds the present-day narrative in a tangible reality, contrasting beautifully with the ethereal quality of the recollections.

Echoes of Authenticity

The voice performances are key to the film's gentle power. Miki Imai imbues adult Taeko with a relatable blend of competence and underlying vulnerability. Youko Honna captures the earnestness, confusion, and occasional bratty indignation of young Taeko perfectly. There's an authenticity here that transcends animation, making these characters feel utterly real. This realism was paramount for Takahata, who often favored pre-scoring (recording dialogue before animation) to allow animators to match lip flaps and expressions more precisely – a departure from the typical post-scoring workflow in Japanese animation that contributes significantly to the film's grounded feel.

The film's exploration of seemingly mundane childhood events – the struggle with fractions, the first crush, the quiet pain of feeling misunderstood – resonates deeply precisely because of its lack of melodrama. It trusts the audience to recognize the universal weight in these small moments. It also, rather bravely for its time and medium, touches upon topics like puberty and menstruation with a frankness that reportedly contributed to its delayed international release. Disney, Ghibli's initial US distributor, was apparently hesitant about how to market a film with such mature themes, particularly that scene. It wasn't until GKids secured the rights that Only Yesterday finally received a proper, thoughtful English dub (featuring Daisy Ridley and Dev Patel) and widespread release in North America in 2016, a full 25 years after its Japanese debut.

A Quiet Triumph

Despite its introspective nature and adult focus, Only Yesterday was a massive success in Japan, becoming the highest-grossing domestic film of 1991. Its triumph demonstrated a significant audience appetite for animated stories that explored complex human emotions with subtlety and grace. It solidified Isao Takahata's reputation as a master storyteller capable of finding profound depth in the quiet corners of life, a counterpoint to the more fantastical adventures often associated with Studio Ghibli.

Watching it today, it feels less like a relic of the early 90s and more like a timeless exploration of the journey toward self-understanding. It asks us, gently, to consider our own younger selves – not just with fondness, but with understanding. What parts of that child still live within us? How do those early experiences continue to shape our choices? It doesn’t offer easy answers, but encourages the reflection itself.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's exceptional artistry, its emotional depth, and its courageous commitment to a mature, character-driven narrative within animation. The dual timelines are masterfully handled, the animation is purposeful and beautiful, and the performances feel deeply authentic. While its deliberately paced, introspective nature might not resonate with everyone seeking typical Ghibli fantasy, its power lies in its quiet truthfulness. It might not have been the Ghibli tape we rented every weekend back in the day, but discovering Only Yesterday feels like uncovering a hidden gem, a poignant reminder that sometimes the most important journeys are the ones we take within ourselves. It lingers, much like a half-remembered scent or a melody from childhood, inviting contemplation long after the credits roll.