What if a miracle cure became its own kind of burden? That’s the unsettling question simmering beneath the surface of Irwin Winkler's 1999 drama, At First Sight. It arrived near the tail-end of the VHS era, a time when romantic dramas often promised straightforward emotional payoffs. But this film, based on a fascinating real-life case documented by the brilliant neurologist Oliver Sacks, dares to explore the disorienting, often terrifying complexities hidden within a seemingly joyous event: the restoration of sight to a man blind since childhood. I remember picking this tape up, intrigued by the premise and the star power of Val Kilmer and Mira Sorvino, expecting one kind of movie and finding something far more contemplative and, frankly, challenging.

Beyond the Meet-Cute

The setup feels familiar enough initially. Amy Benic (Mira Sorvino, carrying the warmth and intelligence she showcased in Mighty Aphrodite), a stressed-out architect escaping the city, meets Virgil Adamson (Val Kilmer), a gentle, self-sufficient spa masseur in a small town. There's instant chemistry, a connection that deepens despite Virgil's lifelong blindness. Amy, driven by love and perhaps a touch of savior complex, researches a radical surgical procedure that could restore his sight. Virgil, encouraged by Amy but facing resistance from his protective sister Jennie (Kelly McGillis, bringing a grounded gravity honed in films like Witness), agrees. The surgery is a technical success. Virgil can see. But this is where the film departs from expectation and delves into its most compelling territory.

The Overwhelming World of Sight

At First Sight isn't truly about getting sight; it's about the bewildering struggle to understand it. Irwin Winkler, known more perhaps for producing cinematic titans like Rocky (1976) and Goodfellas (1990), attempts to visually translate the neurological chaos Virgil experiences. The world isn't suddenly clear; it's an onslaught of disconnected shapes, colors, and movements without context. He knows a cat by touch, but the visual input of "cat" is meaningless, even frightening, until he can painstakingly connect the new sense to his existing knowledge. The film uses visual distortions, fragmented images, and moments of sensory overload to convey this. Does it always succeed? Perhaps not perfectly, sometimes leaning into slightly conventional cinematic shorthand. Yet, the core idea – that seeing isn't the same as perceiving – resonates powerfully. It challenges our ingrained assumption that sight is an intuitive, effortless gift. For Virgil, it’s a new language he must learn from scratch, under the intense pressure of expectation from himself and others.

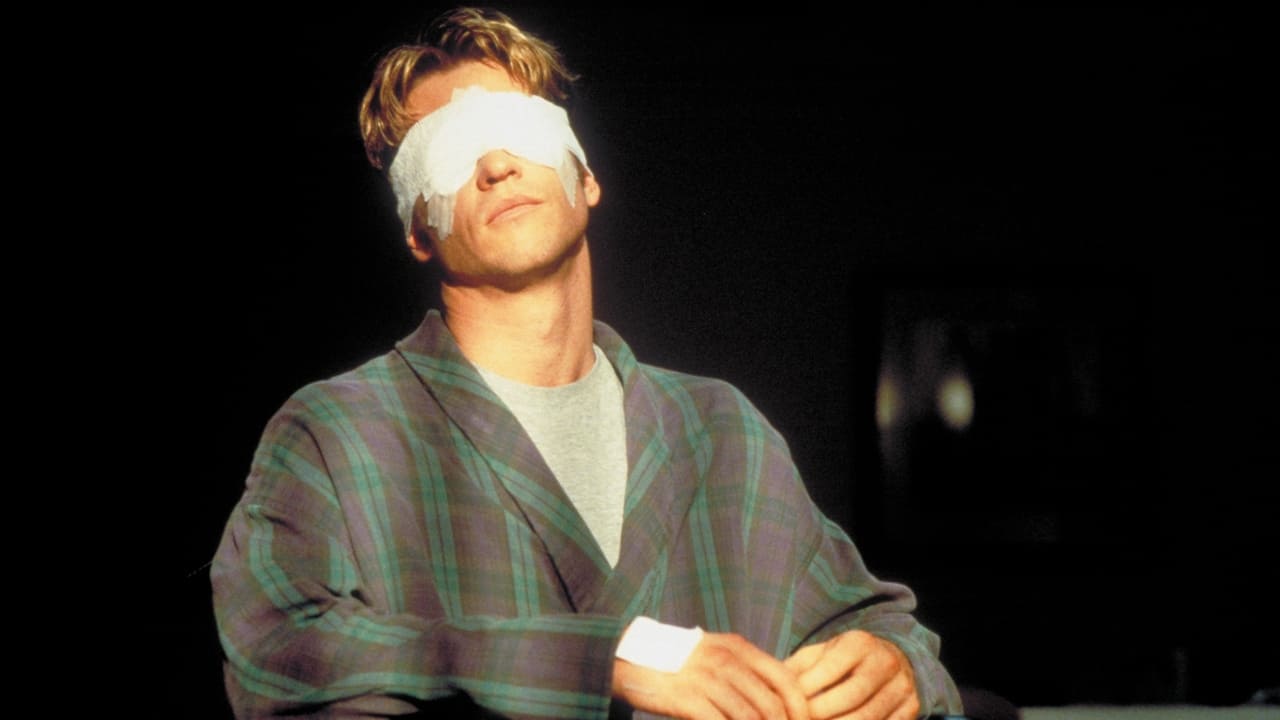

Kilmer's Sensitive Portrayal

The weight of the film rests squarely on Val Kilmer's shoulders, and he delivers a performance of remarkable sensitivity and depth. This wasn't the swaggering Doc Holliday of Tombstone (1993) or the brooding caped crusader of Batman Forever (1995). Kilmer reportedly threw himself into understanding the role, spending time with blind individuals and even wearing specialized contacts to simulate visual impairment. His portrayal of Virgil before the surgery avoids caricature; he embodies a man comfortable and capable within his world. It's after the surgery that Kilmer truly shines, conveying the vulnerability, frustration, and profound disorientation of navigating a newly visible, utterly alien landscape. The moments where sheer sensory input overwhelms him, leading to shutdowns or panicked reactions, feel authentic and moving. It’s a performance that deserved more recognition than it received at the time.

Adapting Sacks: Triumph and Compromise

The film draws its fascinating premise from Oliver Sacks' essay "To See and Not See," documenting the real case of Shirl Jennings. Sacks' writing is renowned for its humanistic exploration of complex neurological conditions, blending scientific rigor with deep empathy. Translating this nuance into a mainstream Hollywood drama, directed by someone primarily known as a producer and starring two major actors, was always going to be a tricky balancing act. Steve Levitt's screenplay understandably leans into the central romance between Virgil and Amy, providing an emotional anchor for the audience. Mira Sorvino is luminous as Amy, embodying the hope and eventual strain that comes with supporting Virgil through his tumultuous journey. Kelly McGillis offers a vital counterpoint, representing the life Virgil knew and questioning the true cost of this "miracle."

However, some critics felt the film smoothed over the harsher, more complex realities Sacks detailed, opting occasionally for sentimentality over stark neurological truth. There's a palpable tension between the film's desire to be a touching love story and its exploration of a profound perceptual challenge. This might partly explain its underwhelming box office performance – reportedly making only around $22 million on a $60 million budget. Perhaps audiences expecting a simple, uplifting narrative were unprepared for the film's more somber and ambiguous reflections on what it truly means to see. It’s a classic case where the fascinating source material presents challenges for a traditional cinematic structure.

A World Re-Evaluated

What lingers long after the VCR whirred to a stop is the film's central, haunting question about the nature of perception and identity. Is sight inherently superior to a life expertly navigated without it? Virgil’s journey suggests it’s far more complicated. He loses the mastery he had in his tactile world, plunged into a visual chaos that threatens his sense of self. The film doesn't offer easy answers, leaving the viewer to contemplate the trade-offs and the unexpected burdens that can accompany even the most desired changes. It prompts a re-evaluation of our own senses, the effortless way we process the visual world, and the deep connection between perception and identity.

Rating: 7/10

This rating reflects the film's thoughtful ambition and Val Kilmer's genuinely moving central performance, which elevates the material significantly. The adaptation of Oliver Sacks' work provides a uniquely compelling premise that sticks with you. However, the score is tempered by a narrative that sometimes struggles to fully reconcile the profound neurological themes with the conventions of a late-90s romantic drama, occasionally dipping into sentimentality where a sharper edge might have served the complex subject matter better. Despite its flaws and its quiet reception upon release, At First Sight remains a fascinating and often poignant exploration of perception, identity, and the unexpected consequences of getting exactly what you wished for. It’s a film that rewards patience and invites reflection, a worthy rediscovery from the back shelves of VHS Heaven.