## A Faded Brothel, A Fragile Defiance: Remembering The Place Without Limits

Some films don't just play out on screen; they seep into the atmosphere, leaving a residue long after the VCR clicked off. Arturo Ripstein's 1978 masterpiece, El lugar sin límites (The Place Without Limits), is one such film. It might not have been the most common rental lining the shelves alongside action blockbusters back in the day – perhaps it was a discovery tucked away in the foreign film section, a recommendation from a clerk who saw something in your cinematic curiosity. Watching it felt like uncovering a hidden, somewhat dangerous truth about the world, rendered in the dusty, decaying light of a forgotten Mexican village.

Based on the novel by Chilean author José Donoso, the film transports us to El Olivo, a town seemingly crumbling under the weight of its own obsolescence, marked for demolition by unseen forces. At its heart, or perhaps its festering wound, is a dilapidated brothel run by the formidable La Japonesa (Lucha Villa). Within these walls lives her daughter, the perpetually melancholic La Japonesita (Ana Martín), and the soul of the film, La Manuela (Roberto Cobo), a homosexual transvestite who owns half the establishment. La Manuela’s presence is a fragile performance of defiance against the crushing machismo of the environment, particularly embodied by the menacing Pancho (Gonzalo Vega), a local strongman haunted by a past encounter with La Manuela.

Ghosts of Desire in a Dying Town

What Ripstein, a director known for his meticulous, often claustrophobic style (think later works like Deep Crimson from 1996), achieves here is less a conventional narrative and more an immersion into a state of being. The air hangs thick with unspoken desires, simmering resentments, and the pervasive sense of entropy. The brothel isn't a place of titillation but of desperation and weary ritual. La Japonesa rules with a pragmatism born of survival, while La Japonesita dreams of escape, trapped by circumstance and her mother's manipulations. The very landscape feels like a character – dusty, sun-bleached, and utterly indifferent to the human dramas playing out within it. Ripstein and his cinematographer capture this decay with a painterly eye, forcing us to confront the ugliness and find a strange, melancholic beauty within it.

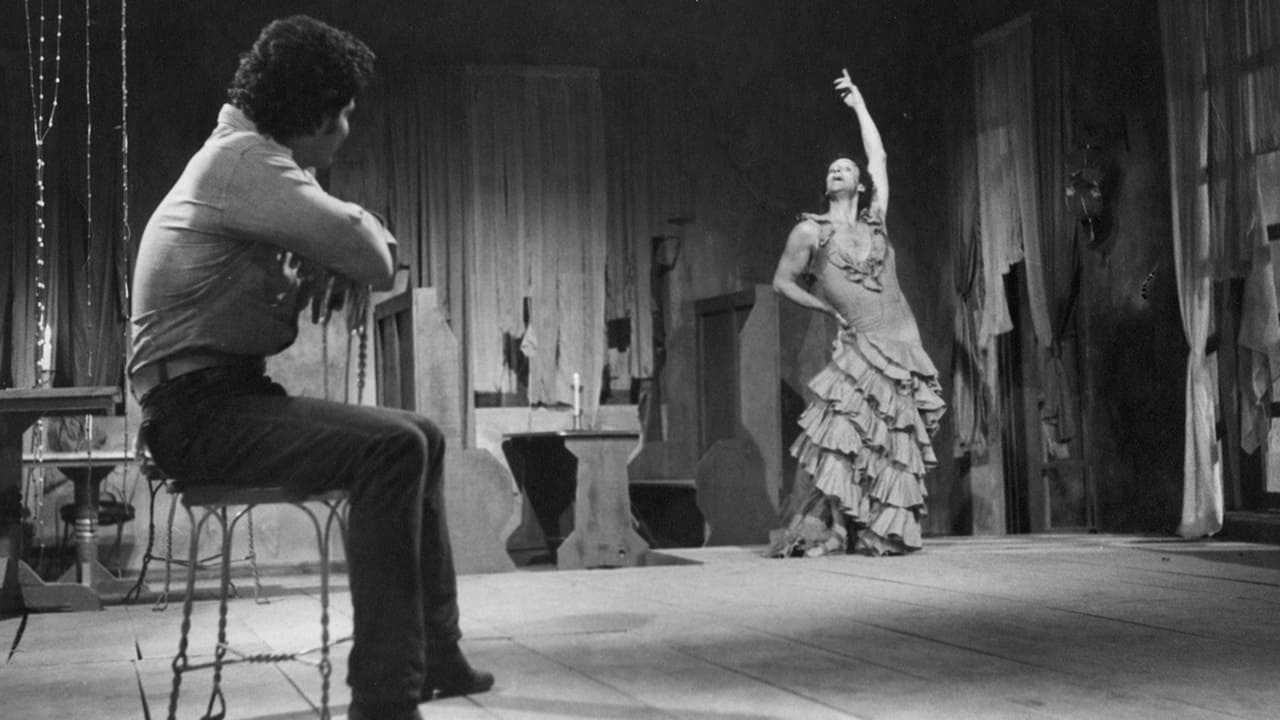

La Manuela: A Performance for the Ages

The film hinges entirely on the extraordinary performance of Roberto Cobo as La Manuela. It’s a portrayal devoid of caricature, steeped in vulnerability, resilience, and a profound sadness. La Manuela’s flamenco dancing, her primary form of expression and perhaps survival, isn't merely entertainment; it's a complex act of self-assertion in a world determined to erase her. Cobo, an actor whose career spanned decades in Mexican cinema, delivers a performance that feels utterly lived-in. There's a weariness in his eyes, but also flashes of defiance, wit, and a desperate longing for connection. His interactions with Pancho crackle with a dangerous, repressed energy – a dance between fear and a strange, unspoken acknowledgment. It was a role that earned Cobo the prestigious Ariel Award for Best Actor, a testament to its power and bravery, especially considering the era's social climate regarding LGBTQ+ representation.

Echoes of Machismo and Repression

The Place Without Limits is an unflinching critique of the destructive nature of machismo and sexual repression. Pancho, fueled by alcohol and a desperate need to assert his dominance, represents the violent intolerance that La Manuela navigates daily. His conflicted feelings towards her – a mixture of revulsion and undeniable fascination – drive the film towards its tragic, almost inevitable conclusion. The film doesn't shy away from the brutality inherent in this dynamic, making it a challenging watch even today. Doesn't this exploration of rigid gender roles and the violence they can incite still feel uncomfortably relevant?

Reportedly, Ripstein and his co-writers (José Emilio Pacheco and Donoso himself) worked closely to translate the novel's dense atmosphere and psychological depth to the screen. Filming took place in a remote, desolate location, which undoubtedly contributed to the palpable sense of isolation and decay permeating every frame. This wasn't a studio backlot; it felt real, lived-in, and forgotten.

Why It Lingers

While perhaps not a typical VHS-era comfort watch, The Place Without Limits represents the kind of powerful, boundary-pushing cinema that could sometimes be unearthed in those video stores. It’s a film that doesn't offer easy answers or catharsis. Instead, it leaves you contemplating the cages we build for ourselves and others, the corrosive effects of societal judgment, and the quiet tragedies that unfold in places the world has chosen to forget. It’s a stark reminder of the power of performance – not just Cobo’s mesmerizing turn, but the performances we all enact to survive.

Rating: 9/10

This near-masterpiece earns its high rating through its courageous themes, Ripstein's masterful direction creating an unforgettable atmosphere, and, above all, Roberto Cobo's transcendent performance. Its deliberate pace and bleak outlook might challenge some viewers, but its artistic integrity and emotional depth are undeniable. It’s a vital piece of Mexican cinema history.

The Place Without Limits stays with you, a haunting portrait of humanity clinging precariously to existence on the edge of oblivion, forever asking: what happens when the place meant for escape becomes the ultimate trap?