## The Unflinching Mirror: Reflecting on "American Me" (1992)

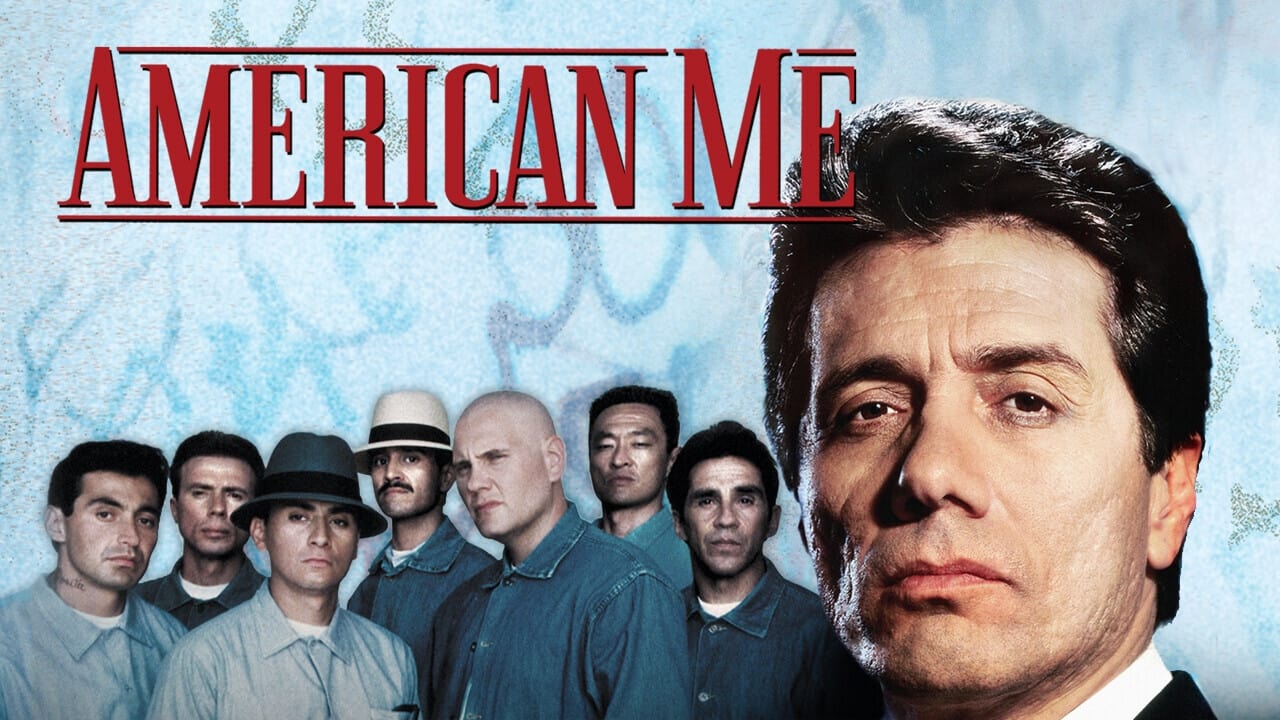

There are some tapes you rented from the video store shelf, nestled between the action blockbusters and sci-fi epics, that felt different. Heavier. The stark cover art of Edward James Olmos's 1992 directorial debut, American Me, promised something raw, something uncompromising. Slipping that tape into the VCR wasn't about escapism; it felt like bracing yourself for a difficult truth. And truth, harsh and unvarnished, is precisely what Olmos delivered – a film that lingers not with the thrill of violence, but with the profound ache of its consequences.

American Me isn't an easy watch. It doesn't offer simple answers or cathartic resolutions. Instead, it pulls us into the brutal trajectory of Montoya Santana (played with stoic intensity by Olmos himself), tracing his journey from a Pachuco youth caught up in the Zoot Suit Riots of the 1940s to becoming the powerful, feared founder of the fictionalized Mexican Mafia ("La Eme") within the unforgiving walls of Folsom Prison. The film asks a devastating question: Can a life forged entirely within the crucible of violence and incarceration ever truly find a path out?

Forged in Fire, Bound by Bars

What immediately strikes you, revisiting American Me today, is its stark authenticity. Olmos, who famously immersed himself in research, spending time with inmates and studying the history of Chicano gangs and prison life, directs with an almost documentary-like precision. There's little Hollywood gloss here. The prison sequences, partially filmed inside the actual Folsom State Prison with inmates as extras, possess a chilling verisimilitude. You feel the claustrophobia, the constant tension, the rigid codes that govern survival. This commitment to realism reportedly came at a cost; Olmos allegedly received death threats from the actual Mexican Mafia due to the film's portrayal (including a controversial depiction of homosexual rape as a tool of power and initiation), forcing him to seek protection for a time. That context hangs heavy over the viewing experience, underscoring the risks taken to tell this story.

The narrative, co-written by Floyd Mutrux (The Warriors associate producer) and Desmond Nakano (Last Exit to Brooklyn), unfolds across decades, showing how the youthful bonds between Santana and his childhood friends, J.D. (a frighteningly volatile William Forsythe, known for intense roles like in Out for Justice) and Mundo (Pepe Serna, heartbreakingly good), curdle into something far more complex and dangerous within the prison system. The film doesn't shy away from the brutality inherent in establishing and maintaining power behind bars, but crucially, it frames this violence not as spectacle, but as the grim currency of a closed, desperate world.

The Weight of Santana

Edward James Olmos, pulling double duty as director and star, carries the film's immense weight on his shoulders. His Santana is a figure of quiet, coiled authority. It’s a performance built on restraint – the calculating eyes, the minimal gestures, the voice that rarely rises but commands absolute attention. We see the flicker of the young man lost decades ago, but mostly we see the hardened product of institutionalization, a man who built an empire within walls but remains trapped by its very foundations. Does Santana ever truly grapple with the monster he created, or the lives consumed by it? Olmos leaves that ambiguous, forcing us to confront the chilling possibility that for some, the cycle becomes the self.

William Forsythe as J.D. is the explosive counterpoint – loyal but impulsive, terrifying in his capacity for violence, yet possessing a strange, almost childlike devotion to Santana. And Pepe Serna as Mundo provides the film's tragic heart. His attempts to reconnect with life outside, his struggles with addiction, and his ultimate fate serve as a devastating commentary on the near-impossibility of escaping the gravitational pull of the past. His journey asks whether redemption is even possible when the system, both inside and outside prison, seems designed to ensure failure.

Beyond the Violence: Legacy and Questions

American Me stands apart from many gangster films of its era. It lacks the operatic grandeur of The Godfather or the kinetic energy of Goodfellas. Its power lies in its bleakness, its refusal to romanticize the life. Olmos uses the violence strategically, not for thrills, but to illustrate the dehumanizing cycle. The film suggests that La Eme wasn't just born from criminal ambition, but as a desperate, distorted form of protection and identity formation for Chicanos facing systemic racism and brutality, both on the streets and within the penal system – a point underscored by the opening Zoot Suit Riot sequence.

Some critics at the time found the pacing deliberate, even slow. But this pacing feels intentional, mirroring the long, monotonous stretches of prison life, punctuated by sudden, brutal eruptions. It allows the weight of Santana's choices, and the decades they span, to truly settle. Made for a modest $16 million, the film wasn't a massive box office hit, but its impact resonated, offering a perspective rarely seen with such unflinching honesty in mainstream cinema. It remains a challenging, vital piece of 90s filmmaking.

Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable power, its courageous authenticity, and the strength of its central performances, particularly Olmos's commanding presence both on and off-screen. It’s a difficult, often harrowing watch, and its deliberate pace might test some viewers, preventing a higher score. However, its unflinching gaze into the abyss of cyclical violence and institutionalization, coupled with Olmos's commitment to realism (even allegedly at personal risk), makes it a significant and unforgettable piece of cinema.

American Me isn't a film you "enjoy" in the conventional sense. It's a film that demands reflection, leaving you with uncomfortable questions about identity, the illusion of control, and the devastating human cost when violence becomes the only language understood. It’s one of those heavier tapes from the rental store days, the kind that truly stayed with you long after the credits rolled and the VCR clicked off.