It starts not with gaslight and corsets, but with whispers in the present day. Young women, their faces open and modern, speak directly to the camera about kissing, about desire, their voices layered over the static elegance of 19th-century imagery. This unexpected prologue to Jane Campion's 1996 adaptation of The Portrait of a Lady wasn't just a stylistic flourish; it felt like a deliberate bridge, an assertion that the intricate traps and yearning for self-determination faced by Henry James's heroine were not relics confined to the past. It was a bold, perhaps even divisive, opening gambit from a director riding high on the global success of The Piano, signaling that this would be no staid literary transfer to celluloid.

### An Inheritance of Constraints

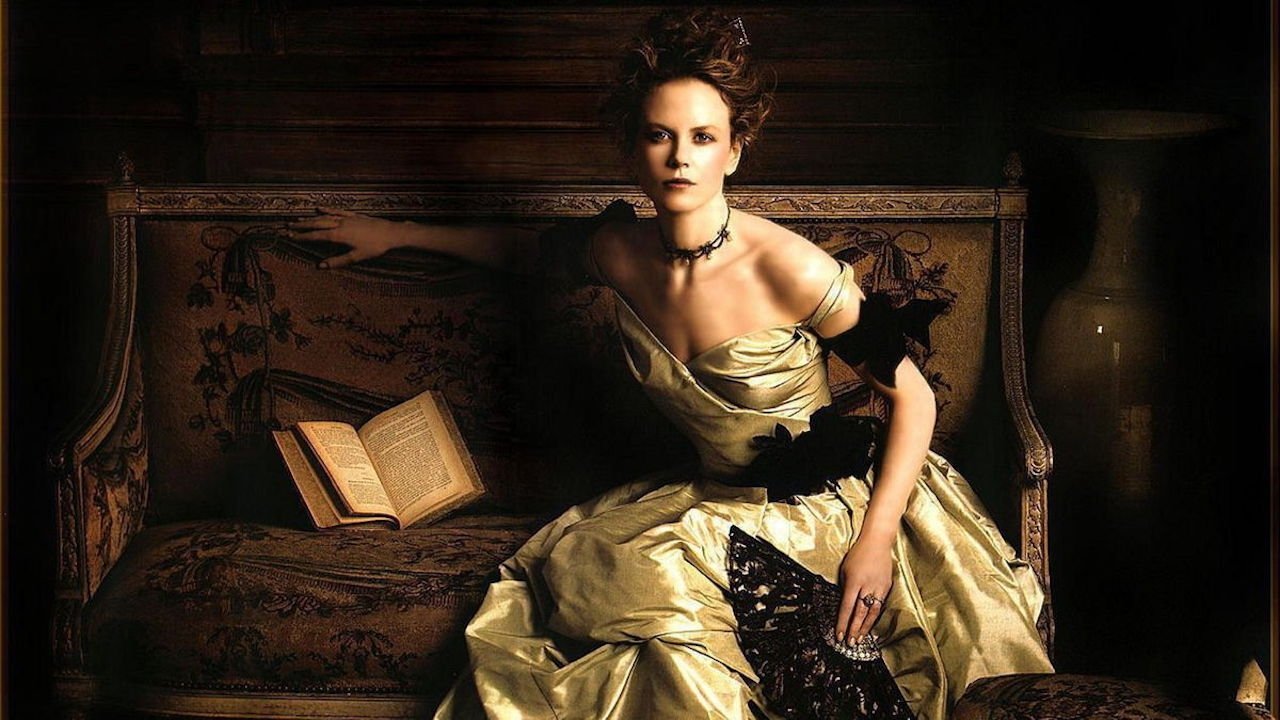

At the heart of this meticulously crafted, often suffocatingly beautiful film is Isabel Archer, brought to life with a fierce, intelligent vulnerability by Nicole Kidman. An American heiress adrift in the sophisticated, stratified world of European society, Isabel possesses wealth, beauty, and a sharp mind, but her most defining trait is her fierce desire for independence. She famously rejects advantageous marriage proposals, wanting to observe life, to choose her own path, unfettered by convention. It's a conviction Kidman embodies with palpable earnestness in the film's early stages – you see the spark in her eyes, the yearning for experience. Yet, this inheritance of freedom becomes its own kind of gilded cage. The film masterfully explores the paradox: how the very pursuit of absolute liberty can lead one into unforeseen, intricate forms of bondage.

### The Collectors of Souls

Isabel's journey is shaped by the magnetic, often predatory figures who orbit her. John Malkovich as Gilbert Osmond is a masterclass in refined cruelty. He’s not a moustache-twirling villain, but something far more insidious: an aesthete of control, a collector of beautiful things, among which he intends to count Isabel. Malkovich delivers Osmond’s pronouncements with a chilling quietude, his pronouncements on taste and form barely concealing a profound spiritual emptiness and a desire to dominate. His performance is a slow-burn horror, the silken tones gradually revealing the steel trap beneath.

Equally compelling, and perhaps even more complex, is Barbara Hershey as Madame Merle. A figure of worldly grace and seemingly benevolent guidance, Merle is the architect of Isabel's disastrous union with Osmond. Hershey, who deservedly earned accolades for this role, navigates Merle’s intricate motivations with extraordinary subtlety. Is she driven by envy, a desperate need for vicarious influence, or something deeper and sadder? Hershey allows glimpses of the calculation beneath the charm, the weary resignation behind the sophisticated facade. The scenes between Kidman, Malkovich, and Hershey crackle with unspoken tensions, a triangle of manipulation, desire, and profound betrayal.

### Campion's Brushstrokes

Adapting Henry James, with his dense psychological landscapes and nuanced prose, is a formidable task. Jane Campion, working from a screenplay by Laura Jones (who also adapted Campion's An Angel at My Table), doesn't shy away from the novel's complexities or its deliberate pacing. She leans into the atmosphere, using the opulent yet often decaying settings – captured beautifully by cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh – to mirror Isabel’s inner state. Sunlight streams through tall windows, illuminating dust motes in seemingly perfect rooms that gradually feel more like prisons. The score by Wojciech Kilar contributes significantly, often melancholic and foreboding, underscoring the emotional weight bearing down on Isabel. Campion's direction is patient, observational, demanding the viewer lean in and engage with the characters' interior lives, much like reading James requires. It’s a film that rewards attention but can feel demanding, even chilly, at times.

### Retro Fun Facts: Inside the Portrait

This ambitious production wasn't without its fascinating behind-the-scenes facets, adding layers to the viewing experience:

- The Modern Prologue's Purpose: That controversial opening? Campion herself explained it was a way to immediately connect Isabel's desires and dilemmas to contemporary women, preventing the story from feeling like a dusty museum piece. It sparked debate but undeniably set a distinct tone.

- Kidman's Immersion: Nicole Kidman reportedly threw herself into the role, not just reading James extensively but also seeking periods of isolation during the shoot to better connect with Isabel's profound loneliness and sense of being trapped.

- Malkovich's Reluctance: John Malkovich initially found Gilbert Osmond so thoroughly unpleasant that he hesitated to take the part. It was Campion's vision and the complexity beneath the cruelty that ultimately convinced him to embody this chilling character.

- Location Authenticity: The film shot extensively in Italy, particularly near Lucca, utilizing historic villas and estates that provided an unparalleled sense of authenticity but also presented logistical challenges inherent in filming within centuries-old structures. This wasn't just set dressing; it was stepping into history.

- Condensing a Classic: Adapting James’s sprawling novel inevitably meant making significant cuts and compressions. Laura Jones faced the difficult task of preserving the psychological depth while creating a viable cinematic narrative, a balancing act that drew both praise for its intelligence and criticism from literary purists for its omissions.

### The Echo of Choice

Watching The Portrait of a Lady today, perhaps rediscovered on a well-worn tape or a streaming service, its themes feel remarkably resonant. In an era still grappling with questions of female autonomy, societal expectations, and the often-invisible ways individuals can be controlled or manipulated, Isabel Archer's story remains potent. The film doesn't offer easy answers. It presents a complex, sometimes frustrating, portrait of a woman whose choices lead her down a dark path, prompting us to consider the nature of freedom itself. What does genuine independence look like, and what are the hidden costs of pursuing it against the grain? The film lingers, not necessarily with warmth, but with the weight of that question.

Rating Justification:

7/10

The Portrait of a Lady earns a solid 7 for its sheer ambition, atmospheric depth, and trio of powerful central performances, particularly from Hershey and Malkovich, with Kidman providing a compelling anchor. Jane Campion's distinct directorial vision and the film's visual richness are undeniable strengths. However, its deliberate, sometimes languid pacing and faithfulness to the novel's psychological density can make it a challenging, occasionally emotionally distant watch, potentially alienating viewers seeking more conventional narrative drive. The controversial prologue, while bold, might also divide audiences. It’s a work of significant artistic merit, deeply felt and intelligently crafted, but its reach might be limited by its demanding nature, preventing it from achieving a higher score based on broader accessibility or consistent engagement across its runtime.

Final Thought: This isn't a comforting period piece; it's a haunting exploration of a soul navigating treacherous currents, leaving you to ponder the intricate, often invisible, architecture of entrapment long after the screen fades to black.