It wasn't always neon lights and explosive action figure tie-ins back in the video rental days, was it? Sometimes, tucked away perhaps in a slightly dusty "Foreign Films" section or recommended in hushed tones by the store clerk who really knew cinema, you'd find a tape that promised something... different. A stark black and white cover, maybe a title that didn't scream escapism. Béla Tarr's 1988 film Damnation (Kárhozat) was exactly that kind of tape – a challenging, atmospheric plunge into a world far removed from the usual blockbuster fare, yet unforgettable once experienced. Forget the feel-good vibes; this one leaves a residue, a lingering chill that speaks volumes about a certain kind of despair.

### Rain Soaked Souls

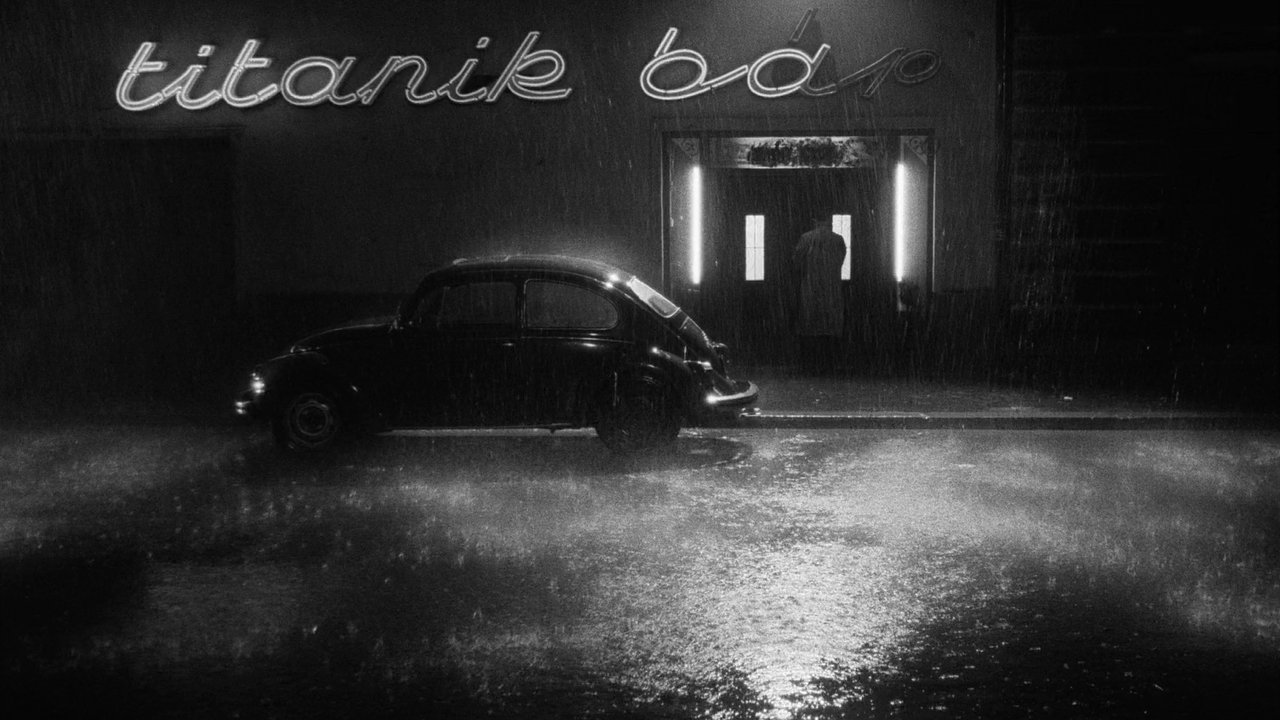

The film opens, and immediately, you're enveloped. Not by plot, necessarily, but by atmosphere. It's perpetually raining or has just stopped raining in the desolate industrial town where Karrer (Miklós B. Székely) drifts through his days. Mud slicks the streets, decay hangs heavy in the air, and the local bar, aptly named 'Titanik', serves as a kind of purgatorial waiting room. Karrer, a man seemingly paralyzed by inertia and longing, becomes obsessed with the bar's melancholic singer (Vali Kerekes), who is married to another man, Sebestyén (György Cserhalmi). This isn't a torrid love triangle in the Hollywood sense; it's a bleak, muted dance of desire, betrayal, and quiet desperation, playing out under perpetually overcast skies. The plot itself, involving a smuggling job Karrer arranges for the husband partly to get him out of the way, feels almost secondary to the crushing weight of the environment and the characters' internal landscapes.

### The Birth of a Bleak Vision

Watching Damnation today feels like witnessing the precise moment Béla Tarr solidified the unique cinematic language that would define his career, leading to later monumental works like Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies. This film marks the beginning of his crucial collaboration with novelist László Krasznahorkai, whose dense, existential prose finds its perfect visual match in Tarr's patient, observational style. The signature long takes are here – extended, hypnotic shots where the camera drifts, pans, and lingers, forcing us to inhabit the space and time of the characters. Gábor Medvigy's black and white cinematography isn't just an aesthetic choice; it's the very fabric of this world, rendering the mud, rain, and peeling paint with a stark, undeniable presence. It’s a far cry from the vibrant palette often associated with 80s cinema, isn't it? This feels like something unearthed from a different, older, sadder time, even though it was contemporary.

### Performances of Quiet Intensity

The acting in a Tarr film is a world away from overt emoting. Miklós B. Székely as Karrer is extraordinary in his stillness. His face, often seen in close-up or reflected in grimy windows, becomes a landscape of unspoken thoughts, of weariness and a flicker of dangerous obsession. You feel the weight of his solitude, his inability to connect or perhaps his unwillingness to try. Vali Kerekes, as the singer, possesses a captivating weariness herself, her songs echoing the film's pervasive melancholy. The sparse dialogue, often delivered in murmurs or resigned statements, puts immense pressure on the actors' physicality and presence, and they deliver performances that feel utterly grounded in this hopeless reality. There’s an authenticity here that’s unsettling because it feels so deeply weary of life itself.

### Forging Art from Mud and Rain

Finding specific, lighthearted "Retro Fun Facts" for a film like Damnation feels almost contradictory to its spirit, but the context of its creation is fascinating. This wasn't a slick studio production; it emerged from the state-funded Hungarian film system of the late 80s, a period of gradual political change and often challenging economic realities. The film's desolate locations weren't elaborate sets; they were real places, imbued with a sense of genuine decay. The collaboration between Tarr and Krasznahorkai wasn't just about adapting words; it was about finding a shared rhythm, a way to translate existential dread into visual poetry. Composer Mihály Víg’s minimalist, often accordion-driven score is inseparable from the film's mood, becoming another layer of the omnipresent atmosphere. You get the sense that the very difficulty of the environment bled into the filmmaking process, forging something uniquely potent and bleakly beautiful. It reportedly took Tarr years to secure funding, a testament to the perseverance needed to bring such an uncompromising vision to the screen in any era.

### Not Your Average Friday Night Rental

Let's be honest, Damnation isn't the kind of film you'd grab for a cheerful movie night with pizza. I distinctly remember encountering films like this in the more curated sections of independent video stores – the kind of place where the owner might nod knowingly if you picked it up, perhaps warning you it was "slow" but "important." It demands patience. It demands attention. Its pacing is deliberate, almost glacial at times, mirroring the characters' own trapped existence. Yet, for those willing to surrender to its unique rhythm and stark beauty, the experience is profound. It's a reminder that cinema, even on a humble VHS tape viewed on a flickering CRT, could transport you not just to worlds of adventure, but to states of mind, exploring the bleaker corners of the human condition with unflinching artistry. Doesn't that challenging potential represent part of the magic of film discovery we sometimes miss today?

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Damnation is a masterful piece of atmospheric filmmaking and a crucial work in Béla Tarr's filmography. Its uncompromising vision, stunning cinematography, and haunting performances create an unforgettable, albeit deeply melancholic, experience. The deliberate pacing and bleak subject matter make it challenging and certainly not for everyone, hence docking a couple of points for general accessibility within the 'VHS Heaven' context. However, its artistic merit and power are undeniable for viewers seeking profound, unconventional cinema from the era.

Final Thought: This is a film that seeps into your bones like the relentless rain it depicts, leaving you contemplating the nature of hope in seemingly hopeless places long after the tape has ended. A stark, essential piece of late 80s European art cinema.