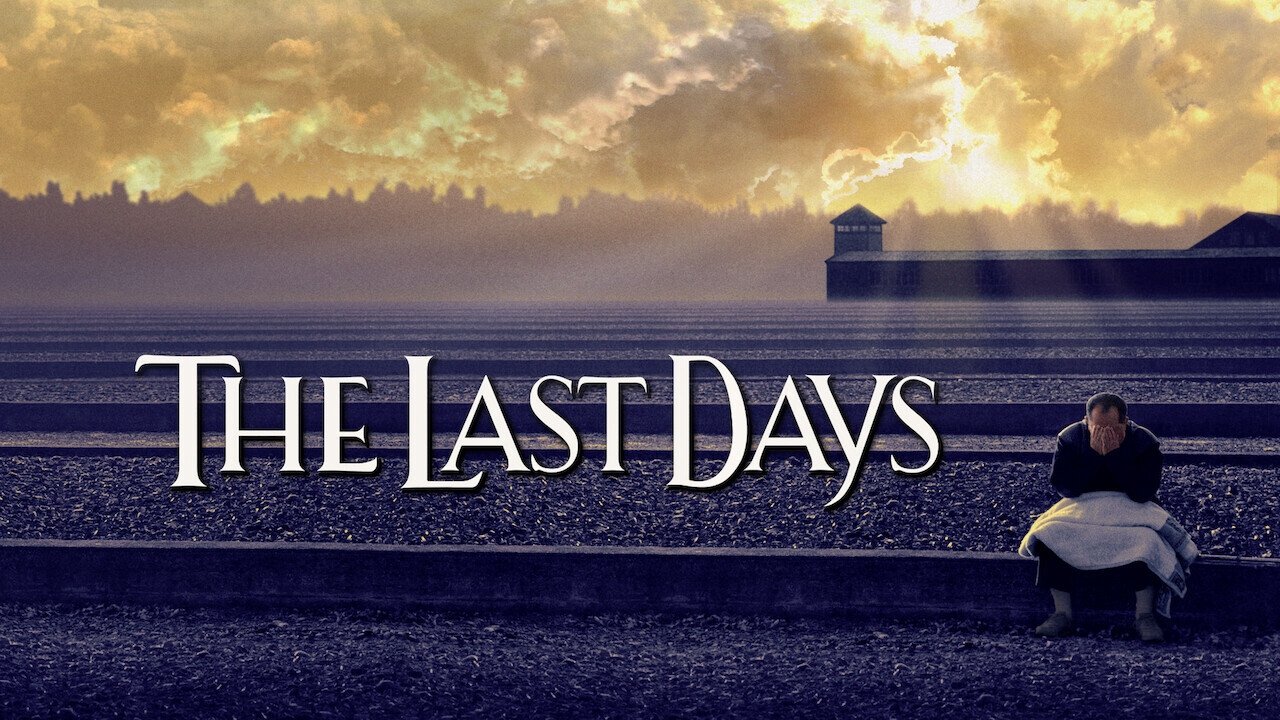

Okay, pull up a comfy chair, maybe dim the lights. Some tapes we grabbed from the rental store promised explosions, laughs, or scares – pure escapism. But every now and then, you'd encounter something else entirely on those shelves, something demanding more than just passive viewing. The Last Days, the 1998 documentary produced by Steven Spielberg's Shoah Foundation, was one such tape. It didn't offer escape; it offered testimony, a stark, vital confrontation with history that felt profoundly important, even nestled amongst the colourful box art of its neighbours. It’s a film that settles in your bones and stays there.

### Bearing Witness

What strikes you immediately about The Last Days is its focused intensity. Emerging in the wake of Spielberg’s own monumental Schindler's List (1993), this documentary, expertly guided by director James Moll, narrows its lens onto the harrowing experiences of five Hungarian Jews during the final, frantic year of World War II. Hungary’s Jewish population faced a uniquely terrifying fate – relatively untouched until 1944, they were then subjected to a brutally swift and devastatingly efficient deportation and extermination campaign by the Nazis and their collaborators, primarily at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The film doesn't try to encompass the entirety of the Holocaust; instead, it finds universal truth in the specific, devastating details of these five lives: Bill Basch, Irene Zisblatt, Renée Firestone, Alice Lok Cahana, and the late Congressman Tom Lantos.

### The Power of Presence

There are no actors here, only survivors. Their 'performances' are raw, unfiltered acts of bearing witness. Watching Irene Zisblatt recount hiding diamonds given to her by her mother, swallowing and recovering them daily to survive, or Renée Firestone search for information about her sister, lost in the chaos, is almost unbearably intimate. Their courage isn't just in surviving the unimaginable, but in finding the strength decades later to articulate that trauma for the camera, for us, for history. Director James Moll makes the wise choice to simply let their stories unfold. The filmmaking is largely unobtrusive, relying on direct-to-camera interviews, poignant archival footage (some of it stomach-churning in its casual cruelty), and contemporary footage of the survivors, sometimes returning to the very sites of their suffering. There’s a quiet dignity in the filmmaking that honours the gravity of the subject matter.

One particularly resonant aspect is seeing the survivors revisit places like Auschwitz or Dachau. The contrast between the present-day quiet of these memorial sites and the horrors embedded in their memories is palpable. It forces a reflection – how can such ordinary-seeming places hold such extraordinary pain? What does it mean to stand where they stood, decades later, knowing what transpired?

### Behind the Silence

The very existence of The Last Days is a testament to a crucial historical project. Following the profound impact of Schindler's List, Steven Spielberg established the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation (now the USC Shoah Foundation) with the urgent mission of recording survivor testimonies before it was too late. The Last Days was one of the first major feature films to emerge from this archive, transforming recorded history into a cinematic experience aimed at ensuring these voices would never be silenced. It’s a staggering thought – the sheer scale of the Foundation’s work, capturing tens of thousands of stories. This film gives faces and deeply personal narratives to that monumental effort. It wasn't just about documenting what happened, but who it happened to.

Interestingly, the film also features interviews with a few former Nazis, including a doctor who worked with Josef Mengele. These moments are chilling, offering glimpses into perpetrator psychology that are as disturbing as they are complex, adding another layer to the film's examination of humanity's capacity for both cruelty and resilience. The score by Hans Zimmer, known for his often bombastic work on films like Gladiator (2000) or The Dark Knight (2008), is appropriately restrained and deeply mournful here, underscoring the emotion without ever overwhelming the testimonies. The film went on to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1999, a recognition not just of its cinematic quality, but of its profound historical and human significance.

### An Enduring Echo

Watching The Last Days back in the late 90s, perhaps on a rented VHS tape viewed on a fuzzy CRT screen, felt different. It was a time when the events of World War II were moving from living memory towards historical record. This film felt like grabbing onto that memory, holding it close. Does it feel different watching it now? Perhaps. The survivors are older, some have passed away, making their recorded words even more precious. The world faces new challenges, yet the lessons about intolerance, dehumanization, and the fragility of peace remain terrifyingly relevant.

This isn't a film you 'enjoy' in the conventional sense. It's demanding, heartbreaking, and profoundly moving. It requires your attention, your empathy, your willingness to confront the darkest corners of human history through the eyes of those who endured it. It’s a film that stays with you long after the tape stops rolling (or the stream ends), a haunting reminder of the importance of memory and the enduring power of the human spirit.

Rating: 9.5/10

This score reflects the film's immense power, historical significance, and masterful execution in presenting incredibly difficult subject matter with sensitivity and respect. The survivors' testimonies are invaluable, and James Moll's direction allows their stories to resonate with profound emotional depth. It's an essential piece of documentary filmmaking.

The Last Days doesn't just recount history; it transmits it, viscerally, ensuring that the final, terrible chapter of the Holocaust for Hungarian Jewry echoes not just in textbooks, but in the heart. What responsibility do we have, having heard these stories? That's the question it leaves burning long after the credits.