Here we go, another journey back to the shelves of the video store, though this time the tape feels heavier, the subject matter demanding a different kind of attention than the usual neon-drenched action or creature feature. I'm thinking about Steven Spielberg's 1997 historical drama, Amistad. Pulling this one off the shelf wasn't about seeking escapism; it was about confronting a piece of history, rendered with a power that stays with you long after the VCR clicks off. The film throws down a gauntlet from its opening frames: who are these men chained in the belly of a ship, and by what right are they held?

The Weight of History, The Power of Cinema

Coming just a few years after the monumental Schindler's List (1993), Amistad felt like another significant undertaking for Spielberg, a filmmaker often associated with wonder and adventure diving deep into the brutal realities of the transatlantic slave trade and the fight for human dignity. It’s a film that doesn't flinch. The initial mutiny aboard the Spanish ship La Amistad is depicted with a raw, chaotic energy, establishing immediately the desperation and righteous fury of the captured Africans led by Sengbe Pieh, later known as Joseph Cinqué.

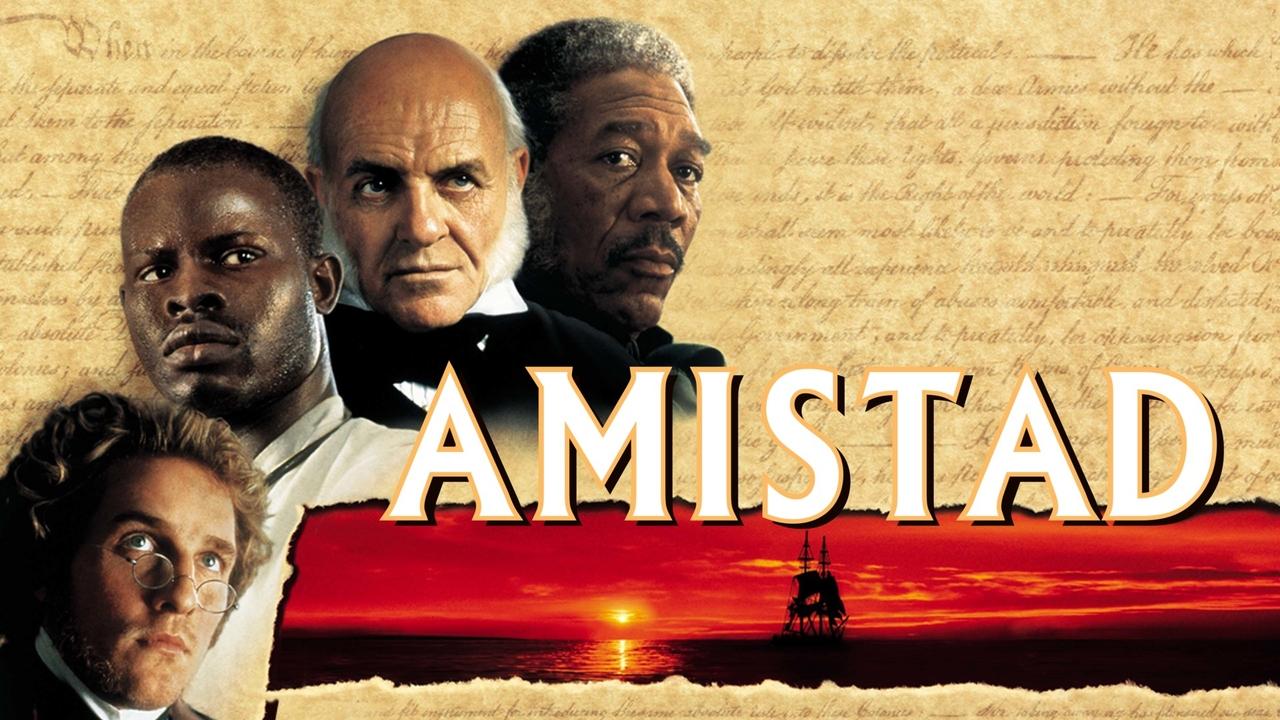

The narrative, penned by David Franzoni, quickly shifts from the high seas to the halls of American justice. The surviving Africans land in Connecticut in 1839, and what follows is a complex legal battle – are they property, or are they free men wrongfully abducted? This question becomes the film's resonant core, examined through multiple lenses: the abolitionist movement (represented by Morgan Freeman as Theodore Joadson and Stellan Skarsgård as Lewis Tappan), the bewildered legal system (initially navigated by a young property lawyer, Roger Baldwin, played compellingly by Matthew McConaughey), and ultimately, the highest court in the land, argued by former President John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins).

Faces of Defiance and Dignity

What truly elevates Amistad beyond a historical reenactment are the performances, particularly that of Djimon Hounsou as Cinqué. Relatively unknown to mainstream American audiences at the time, Hounsou delivers a performance of astonishing power and presence. Much of his dialogue is in Mende, yet his face, his posture, his sheer being conveys volumes – confusion, rage, intelligence, and an unwavering sense of self. It’s a physically and emotionally demanding role, a true breakthrough that remains arguably his finest work. There's a fascinating bit of trivia here: Hounsou, who had only recently learned English himself, initially learned his Mende lines phonetically, guided syllable by syllable. The sheer force he brought to the role under those conditions is remarkable.

Opposite him, Anthony Hopkins embodies John Quincy Adams not as a fiery historical icon from the outset, but as an aged, somewhat eccentric statesman drawn reluctantly back into the fray. His transformation culminates in that powerful Supreme Court argument – a scene reportedly anchored by a seven-page speech that Hopkins, renowned for his meticulous preparation, memorized with characteristic speed. It’s a masterful portrayal of intellect and moral awakening. Morgan Freeman lends his signature gravitas to Joadson, serving as a moral compass and a crucial bridge between cultures, while McConaughey effectively portrays Baldwin’s evolution from a lawyer concerned with property rights to a man fighting for human lives.

Spielberg's Touch and Telling Details

Visually, Spielberg, working with cinematographer Janusz Kamiński (their partnership solidified on Schindler's List), creates stark contrasts: the claustrophobic horror of the Middle Passage flashback versus the austere, formal setting of the courtrooms. The flashback sequence, depicting the unspeakable brutality aboard the slave ship Tecora, is intentionally harrowing, a necessary confrontation with the inhumanity underpinning the entire legal struggle. It’s tough viewing, deliberately so.

The film wasn't a runaway success like many of Spielberg's other works. Made for around $36 million, it brought in about $44 million domestically – a respectable sum, but perhaps below expectations for a Spielberg epic. This might speak to the challenge of marketing such a demanding historical piece to a wide audience. Yet, its production journey is compelling. Producer Debbie Allen was instrumental, championing the project for years before bringing it to Spielberg, believing he had the clout and sensitivity to do it justice. It's a testament to her persistence that this vital story reached the screen with such scope. While debates about historical accuracy inevitably arose (as they often do with dramatizations), the film undeniably brought the Amistad case into mainstream consciousness.

The Lingering Echo

Watching Amistad again now, decades removed from its 1997 release, its power hasn't diminished. It feels less like a typical 90s blockbuster and more like a sobering, essential piece of historical filmmaking that happened to arrive during that era. It’s a film that prompts reflection on the very foundations of justice and freedom, questions that resonate deeply still. What defines personhood? How does language shape understanding and prejudice? The film doesn’t offer easy answers, but demands we engage with the questions. It reminds us that history isn't just dates and events, but the lived experiences and struggles of individuals fighting for their fundamental right to exist as human beings. It was one of those VHS tapes that felt important, one that sparked conversations long after the credits rolled and the tape was rewound.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable power, superb performances (especially Hounsou and Hopkins), and Spielberg's masterful, if heavy-handed at times, direction in service of a vital historical narrative. It successfully uses the medium of popular cinema to educate and provoke thought on profound themes. While perhaps not as rewatchable as lighter fare due to its intense subject matter, its impact is significant and lasting.

Amistad remains a potent reminder that the fight for justice is often a complex, arduous journey, and that giving voice to the voiceless is one of cinema's most crucial callings.